Twenty summers ago, a healthy NFL star died after practice on a scorching day at the Minnesota Vikings‘ training camp. The words still sting and baffle in equal measure. Korey Stringer’s sudden death at age 27 was not from a heart attack, a broken neck or an undetected genetic malady. The offensive tackle succumbed to complications from exertional heatstroke, an avoidable and easily treated condition that sports medicine largely ignored at the time.

The 20th anniversary of Stringer’s death on Aug. 1, 2001, will bring a new round of pain to his family and friends. They will take comfort, however, in knowing that their tragedy changed the world.

Almost immediately, football programs at all levels began reevaluating outdated notions of heat conditioning, hydration and the psychology of pushing through physical distress. “It gave them permission to use common sense,” his widow, Kelci Stringer, said this summer.

The 2010 founding of the Korey Stringer Institute (KSI) — a partnership between Kelci, agent Jimmy Gould, the NFL, the University of Connecticut and Gatorade — has accelerated that progress and expanded it into new sectors. In part because of the group’s advocacy and research, reported deaths by exertional heatstroke during sports have dropped 51% over the past decade, based on data compiled by the National Center for Catastrophic Injury Research. A total of 38 states have changed laws or adopted new guidelines to mandate safety protocols, and an estimated 75% of high schools in the country have cold water immersion tubs available to reverse the onset of heat illness, according to Douglas Casa, chief executive officer of KSI and a professor of kinesiology at UConn.

“Any time there is a major change in how society does things, it’s typically because somebody died or got hurt in some way, shape or form,” said Korey’s brother, Kevin Stringer. “I guess Korey’s death was my family’s turn to pay that cost. It bothers me sometimes if I hear of somebody having a heat-related injury, but I know even if that happens, there is more awareness of what to do. It took a while to get there, but we did.”

‘A perfect storm of all the worst things’

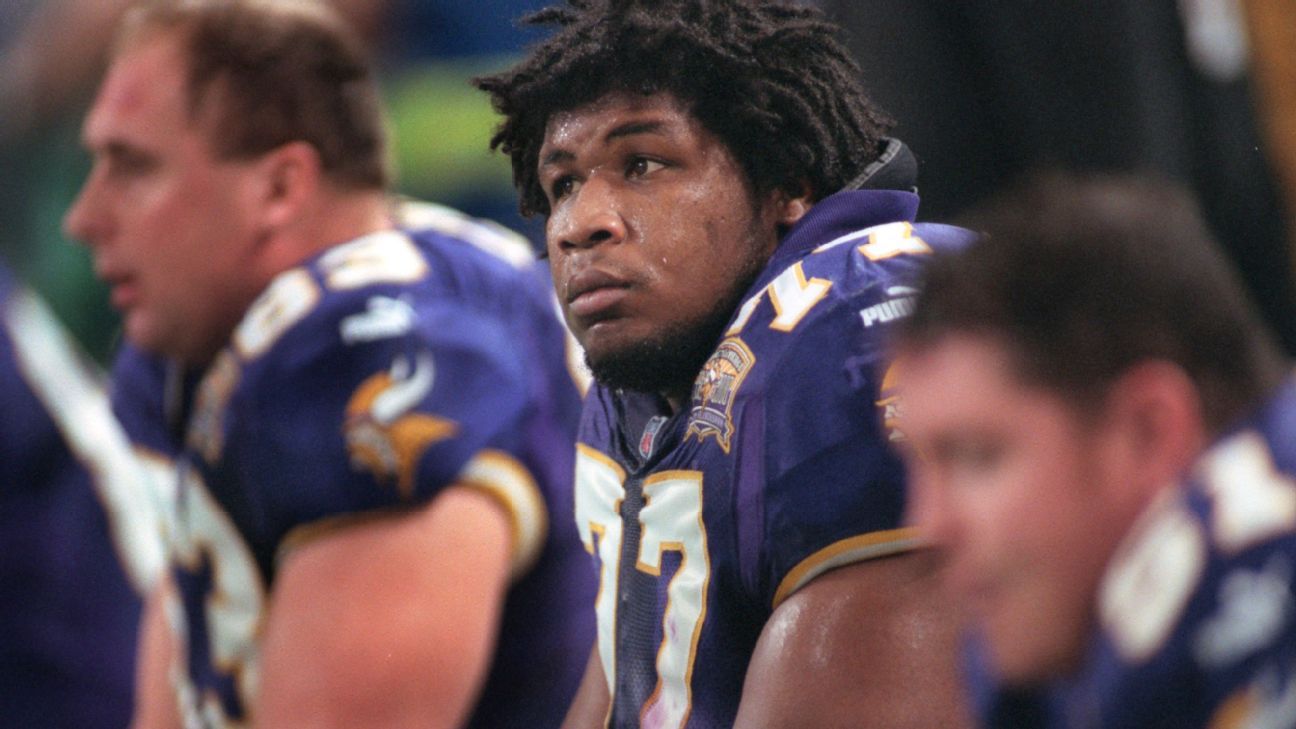

At the time of his death, Stringer had developed into one of the NFL’s best offensive linemen. A first-round pick of the Vikings in 1995, he struggled at times to manage his weight but earned Pro Bowl honors after a stellar season at right tackle in 2000. He reported to the Vikings’ 2001 training camp in excellent shape, at 336 pounds, and seemed poised for cultural stardom.

An Esquire magazine profile, reported in the months leading up to his death and published shortly after, was entitled “The Enlightened Man” and described him as “six feet four inches, 340 pounds of supersized, liver-and-onions-eating, deep-thinking, dreadlocked delight.”

“He was the guy who made you feel like you were his best friend,” said Todd Steussie, a Vikings offensive lineman from 1994 to 2000, “and I guarantee you there were 20 other people on the team that felt the same way. He still pops in my head, to this day, at random times.”

Stringer was an unusually prolific sweater, a trait he acknowledged with quirky humor. Esquire writer Jeanne Marie Laskas noted it repeatedly and with haunting premonition. He always carried a towel, she wrote, because if “you’ve been blessed with an automatic sprinkler system, you should always bring a towel.”

The weather at the start of training camp was stifling, especially for Minnesota. Stringer, who in previous years had struggled to acclimate in the early days of camp, vomited three times during the opening practice on July 30. He left early via a cart and joined athletic trainers in an air-conditioned trailer adjacent to the fields at Minnesota State University, Mankato. A photograph of Stringer vomiting appeared in the next morning’s (Minneapolis) Star Tribune. He told teammates at the time he was angry and embarrassed, prompting a public narrative that he would later ignore the warning signs of exertional heatstroke to finish his final practice without leaving.

The weather was even worse on July 31, and the heat index — a measure of what the weather feels like at a given time based on a combination of temperature and humidity — was nearly 90 degrees when the team took the field in full pads that morning. The Vikings, who played their home games indoors at the Metrodome, practiced as scheduled in the heat. Stringer vomited at least once and left briefly to have his ankle taped but otherwise finished the practice.

He soon began showing signs of distress, one of six Vikings players who suffered heat illness that day. During post-practice work, he slipped while hitting a blocking bag and then fell onto his back with his arms over his head, a moment memorialized by a freelance photographer who initially withheld the shot out of respect to Stringer’s family. Teammate Matt Birk was one of several who called for medical help, and a recently hired athletic trainer led Stringer to the same air-conditioned trailer he had visited the day before.

Exertional heatstroke was well known to military doctors, who treated it regularly for troops working in desert climates. But diagnosis and intervention techniques hadn’t made their way to the NFL. Former commissioner Paul Tagliabue, who retired in 2006, now admits that neither the league nor the Vikings was prepared for what happened next.

“I don’t think that heatstroke was on the radar screen of most teams at that time,” Tagliabue said this summer, citing the mistaken belief that air conditioning could sufficiently cool overheated players.

NFL teams now follow a standard protocol for suspected exertional heatstroke — endorsed by KSI and the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) — that calls for immediately taking the rectal temperature and then immersing those whose body temperature exceeds 104 degrees in a cold tub. According to KSI/NATA protocol, there is a 100% survivability rate if exertional heatstroke victims have their internal temperatures reduced below 104 degrees within 30 minutes of the onset of symptoms.

“A good deal was learned, and teams moved very quickly,” said Tagliabue, who will be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame this summer. “Good lessons were learned and learned well.”

It wouldn’t be in time to save Stringer, however. Neither of the two athletic trainers who aided Stringer in the trailer treated him for exertional heatstroke, according to court documents generated from a series of civil lawsuits over the next decade. He spent 50 minutes there, according to the documents, at first appearing to rest but later turning unresponsive. He was transported via ambulance to a local hospital, where doctors found his internal core temperature to be 108.8 degrees. He died of multiple organ failure about 13 hours later, at 1:50 a.m. local time on Aug. 1, leaving behind a large extended family in addition to Kelci and their son, Kodie, who was 3 years old at the time.

“It was a perfect storm of all the worst things,” Kevin Stringer said. “There weren’t any policies in place, and there were some bad calls made on that day. And it was bad weather. We just did not have that type of awareness back then. The good thing is that it doesn’t have to go down like that anymore. I am grateful for that.”

Steussie had signed with the Carolina Panthers as a free agent several months earlier, but he briefly left Panthers camp and returned to Minnesota to mourn Stringer’s death. He still isn’t over it.

“If you throw him in an ice tub, Korey is alive today,” he said. “It’s that simple, and that makes it so hard to think about.”

The wake-up call, and what happened next

On the hottest days of his career, Matt Birk held tight to what he considered an inalienable truth. “The more you sweat in training,” the saying goes, “the less you bleed in battle.” That belief led to his own personal default setting.

“There were times when you would walk out on that Mankato field and it was hotter than hell, and you had a long practice in front of you,” said Birk, who played center for the Vikings from 1998 to 2008 and finished his career with the Baltimore Ravens from 2009 to 2012. “I can remember saying to myself, ‘Look, you’re not going to die.’ Honestly. ‘You’re not going to die. So come on, let’s do this.’

“So when Korey died, you were like, really? Really? He actually did die. It just hit you that, ‘Wow, you can die playing football.’ I knew you could get seriously hurt. I knew you could blow out your knee. The neck injuries. But gosh, it was unbelievable.”

The NFL made no immediate official policy changes, but Birk was among those who sensed an immediate shift in a practical sense, from more scheduled breaks to greater emphasis on hydration. “The entire culture changed,” he said. The term “heatstroke” itself suddenly cascaded through all levels of football, carrying with it a stark and familiar image of warning.

Former Vikings running back Robert Smith, who also played with Stringer at Ohio State, had never heard a word about heatstroke during his football career — until Stringer died from it.

“Maybe it’s kind of the bubble that you’re in,” Smith said. “But after Korey’s death, people started to talk about how often it actually happens. Maybe not at the pro level, but at other levels of the sport. As we started to learn that, it was really eye-opening to see. It was just devastating.”

Having retired in 2001, Smith worked as a volunteer coach on the youth level in Florida in the following years. He was both thrilled and shocked to see an entirely new landscape of attention to the heat. Having grown up in an era of minimal water breaks and general defiance of weather conditions, he noticed “that it was something that they didn’t play around with anymore. They were scheduling breaks and wouldn’t deviate from that. I had never seen that before in football, and it started happening almost immediately.”

Absent those scheduled breaks, and without a culture of external concern about heat illness, Stringer kept pushing through his final practice. Smith imagines Stringer was determined to “give a little bit extra” after leaving practice the day before and seeing the image of his distress in the morning newspaper.

“That’s really the worst part of it for me,” Smith said, “is thinking about what his mindset was going into that day of practice. He just wanted to make amends for what happened the day before.”

We’ll never know exactly what Stringer thought during his final hours of consciousness. His family, however, doesn’t think he would have been caught up enough in traditional football culture to intentionally push himself through a danger zone. One of the symptoms of heatstroke is lowered cognitive function, making it likely that Stringer didn’t realize what was happening to him. Beyond that, Kelci Stringer said her husband had built enough equity with the team and confidence in himself “to be able to make choices” about exertion.”

“You can never say never, but I really don’t think that’s what happened,” she said. “I would say it was some extreme circumstances with the weather, and the staff was highly untrained. That will never change. No matter how sorry they were. They were highly untrained and incapable of understanding what was happening to him. You put those two together and you had the demise of a player. Period.”

In either event, Stringer’s death created a guardrail for players who once feared they would be judged for moderating their effort in the heat. “It changed the whole culture,” Birk said.

While playing for the Ravens later in his career, Birk said, he noticed a fellow offensive lineman struggling during a summer practice. The player told Birk he was trying to lose weight.

“I remember telling him, ‘Dude, you do not cut weight during training camp.'” Birk said. “I told him, ‘I was on the field when a guy died. You can’t do that. Don’t worry about your weight. Don’t worry about that now. We’ll work on that later.’ He was cutting weight and not eating enough. The effect with being there when Korey passed, it really never went away. It was something that I carried with me for the rest of my career.”

Current protocols and how football has changed

In the aftermath, Kelci and the Stringer family filed a series of lawsuits, efforts that achieved their goal of putting all of the key participants — medical officials, coaches, eyewitnesses — on the record. They led to settlements with Dr. David Knowles, the Mankato-based doctor who served as the team’s lead physician at training camp, as well as with Riddell, the manufacturer of the helmet and shoulder pads Korey was wearing during his final practice. (The Stringers contended that Riddell had a duty to warn users that its products could contribute to heatstroke.)

Jimmy Gould — Korey’s agent, who also served as a family spokesman — said he received a call on the eve of a federal court hearing in 2009 from NFL commissioner Roger Goodell. Goodell and his general counsel, Jeff Pash, requested a meeting. Gould and Kelci traveled to NFL headquarters in New York and agreed on a settlement that included a 10-year NFL commitment to start and help fund the Korey Stringer Institute. (The NFL has continued as a primary sponsor.)

Gould hired Casa, a survivor of exertional heatstroke himself, to lead KSI. In the ensuing years, both the NFL and NCAA would apply many of the protocols and best practices KSI promoted.

“That was a game-changer,” Gould said. “The NFL recognized that it needed to make changes, and it did. To me, there are two parts of life. Is there a problem, and can you admit it? And if there is a solution, will you put the resources behind it to solve it? In the case of the Goodell regime, which includes Jeff Pash, they did. You will hear a lot of people criticizing the NFL for the way it handles player health, but it won’t be from me. They wanted to get this right, and in my opinion, what happened to Korey will never happen in the NFL again.”

At the very least, it would require a significant departure from current protocols for an NFL player to die of exertional heatstroke. The league starts each summer by distributing video content from Casa to train and/or refresh team medical personnel on hydration, warning signs such as cramping, cold tub treatment and return-to-play advisories.

Current Vikings athletic trainer Eric Sugarman, who joined the organization in 2006, said that heat illness is a prominent part of the hourlong speech he gives to players at the start of training camp, emphasizing that “it’s one of the most preventable illnesses that we deal with.”

Football players can lose 8-12 liters of fluid per day during the preseason, Sugarman said, so the first step in avoiding exertional heatstroke is to maintain hydration. Every Vikings player undergoes daily urine tests to gauge hydration levels, known as “specific gravity.” Players are given benchmarks they must hit in order to participate in that day’s activity, a policy that likely would have prevented Stringer from practicing on his final day.

Based on current protocols, Stringer almost certainly was not fully recovered from his vomiting episodes during the first practice to merit a full return to the second. In fact, NFL protocols now call for a player to be removed from practice entirely after vomiting once. In addition, under the NFL’s current collective bargaining agreement with the NFL Players Association, players do not put on full pads until the seventh day of training camp, at the earliest.

NFL teams widely employ “Gatorade scales,” devices that calculate weight loss during practice and prescribe a consumption plan to rehydrate. Some teams use core temperature sensors that are ingested and, for the duration of practice, transmit players’ core body temperatures to the medical staff in real time. Vikings players (and coaches) are prohibited from wearing the kind of rubber shirts they once used to lose weight on hot days. And every team’s emergency action plan, required and approved by the NFL’s health and safety office, spells out where cold tubs are located, the duration of the cooling process (which can be different for each player) and the point at which an ambulance should be called.

“Preparation is the key element,” Sugarman said.

Meanwhile, KSI has turned much of its focus toward the labyrinth of state entities and individual high school associations that govern sports below the college level. To win adoption of KSI’s protocols for youth athletes in New York, for example, Casa had to work separately with four different entities with jurisdiction for public, private, independent and Catholic league schools.

In the past two years, Casa has visited 19 states, testifying in front of legislators or meeting with local organizers. He has 15 more states on his schedule over the next nine years. In some cases, the work is so granular that Casa has brokered meetings between school districts and local emergency services to help them understand how long to cool an exertional heatstroke victim before transporting the person to the hospital. Another time, he served as an expert witness in a case that questioned whether school medical personnel have a legal right to administer rectal temperature checks to students.

The quantitative progress, according to Casa, has included the doubling of high schools with cold tub immersion facilities around the country. Overall, the United States has averaged 2.2 sports-related deaths by external heatstroke per year since 2012, down from 4.5 from 2001 to 2011, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Injury Research.

“The states we have visited have made quantum leaps in their policies,” he said, “but it shows you it takes a lot of effort and time because it’s state by state.”

KSI has grown to a full-time staff of 22, with another 83 committed volunteers, allowing it to branch into research for the Defense Department as well as test experimental hydration products for companies, among other projects. That growth allowed Kelci Stringer to step back from its management and spend three years living in Panama with her daughter, True, who is now 11. They returned to the U.S. last year during the COVID-19 pandemic and now live in Charlotte, North Carolina.

“I had to make a decision,” Kelci said. “Am I going to be Korey Stringer’s widow, or am I going to be Kelci Stringer? Now I can say, both, but I had to remove myself to be able to see the bigger picture. The institute needed to build more legs to stand on other than just me, and they have. It’s turned out so well.”

Said Gould: “The hope has been that KSI can be transformative. We want to be able to say that when someone goes off to play sports, they will come home.”

‘Find the way’: How Stringer’s memory lives on

Twenty years on, the echoes of Stringer’s life still reverberate around his family. In interviews this summer, many of them recounted instances of strangers telling them stories about Korey.

His sister, Kim, lives in their hometown of Warren, Ohio, where Korey once dropped off his entire $15,000 Pro Bowl check at the Rebecca Williams Community Center, an act of kindness the family learned about years later. She recently received an unsolicited message on Facebook from a man who lived in Maine. The man’s father had closed a Vikings-themed sports bar in New Jersey and wanted to send her a sizable shipment of photos and other memorabilia they had collected to honor Korey.

“He told me, ‘Your brother touched so many lives, and I just want you to know that people remember him,'” Kim said. “People haven’t forgotten him, and that’s such a beautiful thing.”

When Kelci arrived in Charlotte, employees of the moving company noticed some old family photos. One had Korey in it, prompting them to recount how they were warned about his death while playing high school football. And when Kodie moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in music production, the leasing agent at his apartment building recognized his name and told him that he knew his father to be a kind and gentle man.

Kodie is a living monument to that aesthetic, Kim said, right down to the way people are drawn to his quiet and engaging personality. Now 23, Kodie decided against extending his high school football career in college, saying he didn’t want to “waste the time” of coaches who would eventually find out that he didn’t love the game.

“Actually,” Kodie said, “I just didn’t understand it. As a kid, I hated it.”

In the 2001 Esquire profile, Laskas revealed the story behind one of Korey’s tattoos. It included the letters “FTW,” which stood for “F— the world.” But he later reimagined its meaning after marrying Kelci, having Kodie and making the Pro Bowl. It now meant, “Find the way,” Laskas wrote.

Those who mourned the loss of Kodie’s father can rest assured that his son continues to find his way. Perhaps you noticed him earlier this month on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, dancing onstage behind the mashup DJ Amorphous, a college friend who was performing with singer Kelly Rowland.

If you looked closely, you might have seen the gold chain around Stringer’s neck. It included a Vikings pendant given to his grandfather by Korey many years ago. It made its way back to Kodie, and he wears it every day. His father is not forgotten.