PHILADELPHIA — Philadelphia Eagles defensive coordinator Jonathan Gannon warns that whatever you do, never — under any circumstances — invite coach Nick Sirianni to play a game of blackjack.

Or chess. Or HORSE. Or anything that even remotely involves winning or losing. You’ll come to regret it.

“The guy is, in my opinion, like exhaustingly competitive,” said Gannon, via the Eagles team website.

Gannon worked alongside Sirianni on the Indianapolis Colts’ staff from 2018 to 2020 before joining him in Philadelphia this offseason — Gannon serving as cornerbacks coach and Sirianni offensive coordinator — and would often be sucked into Sirianni’s competitive aura.

“He’d come in and he’d start drawing up plays and I’d say, ‘Nick, this takes that away.’ And it would [turn into] these three-hour conversations where I’d be like, ‘Dude, I gotta go.’

“You don’t want to [challenge him to a competition] because he’ll probably beat you, and if he doesn’t beat you, he’s not going to let you leave before he does beat you somehow. … He’s a wild man, now. He’s a wild man.”

Sirianni, 39, enters the job as Eagles head coach as a relative unknown outside the NFL bubble.

His foray into the mainstream by way of an introductory news conference in late January made for a shaky first impression. Standing alone in the NovaCare Complex auditorium as he addressed the media virtually, he appeared nervous and too focused on his notes on the lectern, leaving little room for personality or natural command to shine through. The awkward session brought the critics out in full throat and only heightened the concerns of those skeptical of the Doug Pederson firing, while intensifying questions as to why qualified minority candidates, such as Kansas City Chiefs offensive coordinator Eric Bieniemy, weren’t more seriously considered during the Eagles’ hiring process.

Sirianni is taking over a 4-11-1 team and replacing the only Super Bowl winning coach in franchise history in one of the country’s fiercest media markets. The organization has been struck by dysfunction, and is in the midst of a roster transition which included the departure of one-time franchise quarterback Carson Wentz. Sirianni is not only taking on playcalling and head-coaching duties for the first time, but has assembled the youngest coaching staff in the NFL as his support system. The average age for head coaches and coordinators for the 2020 season was 49 years old. Sirianni and his top lieutenants average out to 35.

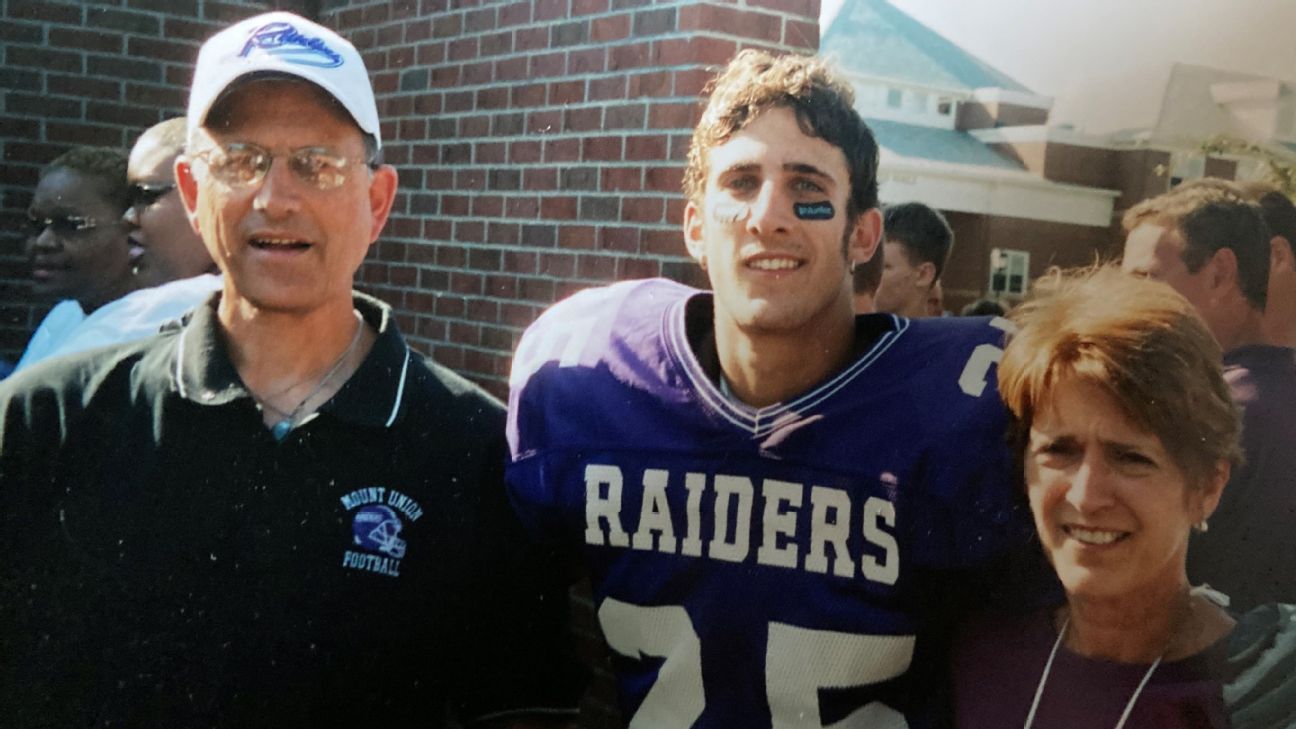

The deck, in many ways, is stacked against Sirianni. But those close to him tell ESPN they aren’t sweating it. They have seen characteristics develop in him over time that they believe will carry him through the grueling responsibilities of being an NFL head coach. Like strength and empathy, heightened by a college football injury that nearly cost him his leg and his life. Deep knowledge of the game, gained from a lifetime of being surrounded by quality football coaches from his father, Fran, to University of Mount Union legend Larry Kehres to Colts coach Frank Reich. And an insane competitive streak that was ignited by his older brothers when he was younger and has seemingly only grown in ferocity.

A near loss of limb, and life

Sirianni’s parents, Fran and Amy, were in their backyard in Jamestown, New York when they got the phone call Nick was injured. They immediately jumped in their car and raced off toward Mount Union in Alliance, Ohio.

It happened at a September football practice during Sirianni’s sophomore season in 2001 — a day after 9/11, his parents said. A wide receiver, he lined up on the right side of the field and ran an in-route. “I was putting a little sauce on the route,” Sirianni told ESPN. “I was going to make a stick to the post, and then I was going to break it off to the end. Well, I make a stick to the post and my ankle kind of goes a little bit. I finished off the route and now I’m going to make that cut to the end and [the ankle] goes all the way.”

The initial diagnosis from doctors was ligament damage to the right ankle that would sideline him a few weeks. But when he got back to campus, his leg started to go numb and was quickly rushed back to the hospital. He was suffering from compartment syndrome, which is when intense swelling stymies blood and oxygen flow, causing blood to build up to dangerous levels near the injured area.

“I still remember this because it was excruciating pain. It just felt like someone had an air pump and they were just pumping air into my leg. Pumping, pumping,” Sirianni said.

“When they opened up my leg to release the blood out of there, the muscle fell out. It had torn in half [as part of the original injury]. So they fixed the injury, but there was so much swelling there, they couldn’t sew me back up.”

That left him in the hospital for a week with an open wound. Six weeks later, he developed a staph infection. That is when the situation got very serious.

“That was the one that I almost lost my leg on,” Sirianni said. “And if it went any further, lost my leg or life.”

He got sick and returned home to Jamestown. He was admitted to the local hospital, where he stayed for another week-and-a-half, receiving eight IVs a day. Sirianni was able to pull through. Fran and Amy credit the local medical staff, and prayer, for saving their son’s life.

But the doctors said he probably wouldn’t play football again, and might not even be able to run again.

“I’m like, forget that, I’m playing football again. You can’t tell me that,” Sirianni said.

He only spent a couple weeks at home before returning to Mount Union, where he got around on crutches and dressed the wound three times a day by himself, all in the name of wanting to be back among his teammates and friends.

Months of rehab followed. Fran and Amy remember Nick sprinting up and down the street in front of their Jamestown house and running around cones at the nearby field, over and over, so determined to get his football career back.

He returned to game action on Sept. 7, 2002 against Wisconsin-Whitewater. Sirianni erupted for four catches and 110 yards with two touchdowns in a 30-14 Mount Union win. The Purple Raiders went on to capture their third straight Division III national championship that season.

“When he got back on that field, the next fall, we were all emotional,” Amy said. We were all crying because we just thought …”

“He had been blessed,” Fran said, finishing Amy’s thought.

“I just admire him for his bravery in dealing with all that,” Amy said.

Sirianni caught 52 passes for 998 yards and 13 touchdowns as a senior, and spent one year playing for the Canton Legends of the Atlantic Indoor Football League after graduating.

During his recovery, Sirianni’s brother, Mike, who is the head coach of Division III Washington & Jefferson College in Pennsylvania, showed support for his little brother by writing Nick’s jersey number, 25, on the hat he wore on game days. Sirianni took that idea and made it a signature of his own. He now places decals on his visor of injured players who are unable to participate — he did it last season for Colts players Parris Campbell and Marlon Mack — so they know they are being thought of and are properly represented.

“It’s more than just that,” said Sirianni, who has a scar on his right leg that runs from his knee to his ankle. “It’s reaching out to them, it’s talking to them, it’s caring for them.”

Added Amy: “He has kind of new empathy for someone else who has gone through an injury. … When you go through something yourself, you can relate to someone who also was going through a bad time.”

A new chapter begins.#FlyEaglesFly pic.twitter.com/AFWghGm1au

— Philadelphia Eagles (@Eagles) January 25, 2021

Fist fights and casual attire

The competitive seed was planted early.

Sirianni is the youngest of three boys. He’s nine years younger than his oldest brother, Mike, and six years younger than Jay. It’s a family of football coaches. Mike has been coaching at the collegiate level since 1996, and Jay took over for Fran as head football coach at Southwestern Central High School following Fran’s 40-plus year coaching run that landed him in the Chautauqua (N.Y.) Sports Hall of Fame.

The family traveled often. Serving as a metaphor for Nick’s station in life when he was younger, he always drew the middle seat on trips while his older siblings got the window seats, ever encroaching on his space.

“He would be crushed on one side and the other side, and he’d have to fight both of them when we were in the car until Fran would have to stop and give one of those, ‘Don’t make me come back there!’ He was always pushed by them in everything,” Amy said.

“I think he may have been the most competitive of the three of them,” Fran spoke of Nick.

His longtime friend, Tom Langworthy, was wired similarly. They’d battle in basketball in the driveway and football in the backyard. One time, they even created their own Olympics, turning Jenga, Jeopardy and miniature golf into near blood sports.

“Nick and I would get in, like, fist fights,” Langworthy said. “And then a few minutes later, it’d be just back to normal, just how brothers do.”

When Sirianni, a physical education major, graduated from Mount Union, he served as an entry-level football assistant at his alma mater. Making $8,000 a year, he and a bunch of other post-grad coaches stayed in a house together right off campus. Sirianni had a room on the first floor without heat. It was McDonald’s by day and Subway by night. It might not have been much, but that house doubled as a coach think-tank, with eventual Division I coaches such as Toledo’s Jason Candle and Iowa State’s Matt Campbell roaming the halls.

The alpha levels were high. Whether it was wagering on PlayStation duels (College Football being the game of choice, of course), debating who had the better football careers at Mount Union, playing cards and darts, or duking it out in rec league basketball, there was always a degree of friendly competition mixed in with admiration they shared for one another.

“These turned into almost fistfights sometimes because of how much we competed with each other,” Sirianni said.

Campbell says Sirianni is “such a great coach, because he is obsessed with being the best, not being embarrassed and doing everything in his power to really put out to become the best version of himself that he can be. That is really what makes Nick special: he’s got that very serious obsession, but he’s also got a great heart and a great spirit about himself.”

It drove him pretty quickly up the career ladder, from Mount Union to Indiana University of Pennsylvania to the NFL. He and Todd Haley used to work out at the same YMCA near Haley’s summer home in Chautauqua Lake and they developed a common respect talking shop in-between sessions. When Haley was named Kansas City Chiefs head coach in 2009, he brought Sirianni on as offensive quality control coach. After four seasons in Kansas City, he moved onto the Chargers (2013-17), where he served as quarterbacks coach and wide receivers coach, before becoming Reich’s right-hand man in Indianapolis in 2018.

When he got the Colts’ offensive coordinator job, he told his wife, Brett, his days of sleeping in the office were likely over, because that’s not what O-coordinators typically do.

“She was like, ‘Yeah, right. You’re sleeping in the building,'” Nick said. “I can’t tell that story any more times, she’s just not gonna believe me, because I’m probably gonna have to sleep there as a head coach as well.”

Sirianni has had a few more cracks at the media thing since the opening news conference and appears to be more comfortable, but no amount of reps are going to totally flatten the edges or shape him into the traditional head-coaching mold. We’re learning he’s excitable and can go off on tangents when he lands on a topic that revs him up, steering the conversation toward destinations unknown. Where predecessors like Chiefs coach Andy Reid and Pederson were more even-keeled, Sirianni’s RPM needle will jerk into the red.

The Eagles knew he had a different style from the jump. Sirianni was on vacation in Florida when he got the call to interview at owner Jeffrey Lurie’s winter home in nearby Palm Beach in February. He didn’t have a suit with him, so Sirianni rolled into Lurie’s $30 million lakefront mansion dressed in casual clothes. The team brass dressed down as well to make him feel comfortable, setting the tone for a marathon pow-wow that spilled into the next day. At one point, it looked like a football practice might break out as a result of Sirianni’s enthusiasm.

“I remember there was a moment in the coaching interviews where we talked about the quarterback position, and Coach stood up and he showed us exactly what he was looking for. I was waiting for him to tell one of us to go run a route,” general manager Howie Roseman said. “I think you saw that passion, that energy, and that attention to detail right away in the interview process.”

The hope is that those qualities help carry him as he gets his footing and tries to lead the Eagles out of the ditch and back toward prominence.

“He’ll be a hard worker. We’ve seen the nights and the time he puts into it. He’ll be compassionate,” Amy said.

“You’re going to see somebody that’s obsessed to prove,” added Campbell, “that he’s earned the right to do this.”