A lot of fans seem to hate watching James Harden play. I get it. There is a numbing effect to the thump-thump-thump of Harden dribbling 20 times while four teammates stand in places chosen by Harden.

But I have a soft spot for the visual Harden experience. He inspires a chess match unlike anything in the NBA. The high-volume step-back 3-pointer transformed Harden into something unprecedented, or very close: a player who could score one-on-one from anywhere.

On lots of possessions, the Rockets no longer had to run plays for Harden — no longer had to engage in things we used to know as basketball. They began to view picks, one of the game’s fundamental building blocks, as a hindrance.

“We used to talk about the screen as an escort for a double-team,” Daryl Morey, Houston’s GM, told ESPN last season. “Why even give the defense the option?”

How were you to defend such a player? Few teams boast an elite wing defender who can stay with Harden one-on-one. Press him too hard, and you risk a 3-shot foul — the most efficient play outcome possible. Some teams — notably the Milwaukee Bucks and San Antonio Spurs — had defenders drape themselves over Harden’s left shoulder, almost climbing atop his back, and force him toward Clint Capela under the rim.

Earlier this season, teams began following the Denver Nuggets‘ lead and trapping Harden the moment he crossed half court. They had some success when both Russell Westbrook and Capela were on the floor — one non-shooter to ignore on the perimeter, another conveniently positioned near the basket. Houston promptly traded Capela.

The reality is no one scheme can contain the league’s best alpha ball handlers. They are too good, with too much shooting around them. Show them a steady diet of anything, and they will pick it apart. Elite defenses can limit the bleeding, but they still bleed.

If those ball handlers know a trap is coming, and from where, the reads become easy. If the pressure comes early in the shot clock, the offense can drive-and-kick three, four, five times. The ball might ping all the way around and return to the superstar who started everything. Good defenses can scramble through a few rotations. Drag them through a few more, and they usually break.

Defenses have to mix things up, but every mixture leans toward a certain flavor. That leaning might depend on a lot of variables: supporting personnel on both sides, time and score, coaching preferences.

But as I wrote in reference to the battle between Donovan Mitchell and Jamal Murray, the correct leaning might be toward amped-up pressure in the back half of the shot clock — pressure that makes it so the superstar surrenders the ball without time to get it back. It is not manic pressure for the sake of it. It is aggression designed “to make everyone else beat you” under time pressure, with the shot clock acting as a sixth defender.

And it is how the Lakers have contained Harden and the Rockets in wresting control of this series in Games 2 and 3. Houston has still scored 111.6 points per 100 possessions over those two losses. That’s good! It would have ranked ninth or 10th in the regular season. Harden had 60 points on 17-of-35 shooting combined in those games. But those numbers are manageable for the Lakers now that Frank Vogel has loosened the spacing for LeBron James and Anthony Davis on offense by mothballing his centers. (Playoff Rajon Rondo soaking up a lot of those center minutes has been huge.)

Much of the talk surrounding this series has been about how that lineup adjustment might provide oxygen for the Lakers’ half-court offense, but this team made defense its bedrock all season. The Lakers ranked third in points allowed per possession, and No. 1 in the Western Conference. LeBron bought in from day one, and the rest of the team followed suit. Credit Vogel for reinforcing this culture, and Vogel and his staff for crafting a killer game plan after Houston snatched the opener.

I can imagine the Lakers’ mantra for its trapping defense might be: Defend one pass. If you can snuff that first catch-and-shoot opportunity out of the trap, you have a chance to reset your defense and force Houston to manufacture a worse shot — often without further involvement from Harden.

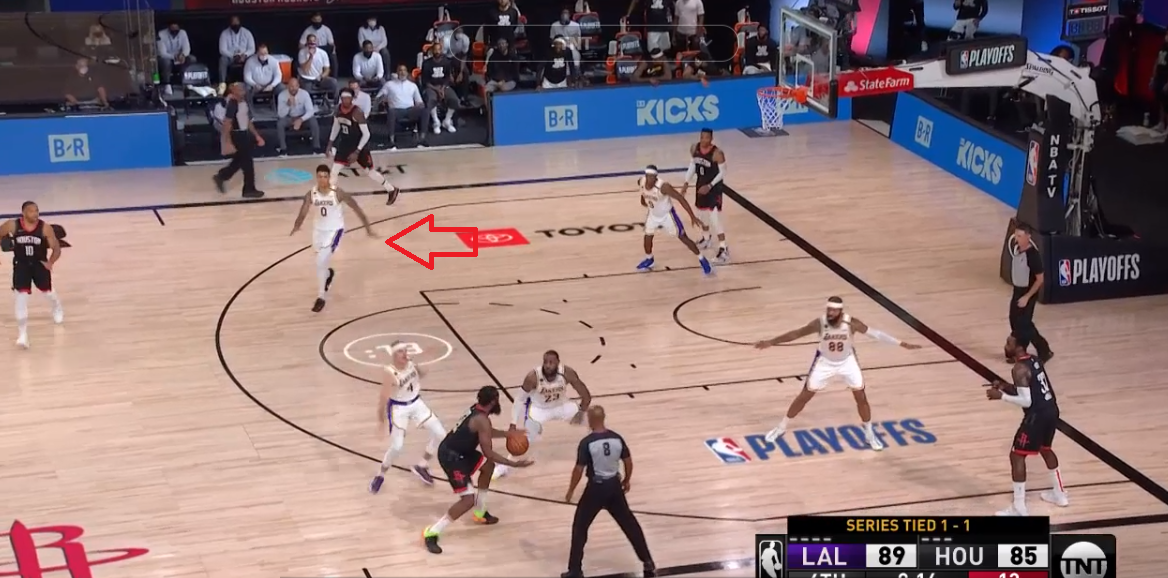

The Lakers’ dream defensive possession looks something like this:

The Lakers are ready for that first pass to Eric Gordon. As the trap cinches, Kyle Kuzma positions himself between Gordon and Robert Covington — prepared for either alternative:

Two more passes follow, each easier and more predictable to defend than the last. The possession dies.

The Lakers spring that trap with 13 on the shot clock — enough time for Harden to get back into the play. Instead, he loiters in the same spot for almost 10 consecutive seconds — across the floor from the action, 30 feet from the rim.

Harden often recedes toward half court once he relinquishes control of a possession. The Lakers’ late-trap strategy is a bet on Harden’s passivity.

(This isn’t limited to Lakers traps. With Game 3 slipping away, Harden faded out of three straight empty Houston possessions spanning 6:10-5:10 of the fourth quarter. He never touched the ball on the middle one. On the first and third, he passed off after crossing half court and did not touch it again — or anytime once the shot clock ticked past 18. Westbrook was on the bench. The possessions ended with: a Covington turnover; Kuzma blocking a flailing Jeff Green attempt near the rim; and Green throwing the ball out of bounds.)

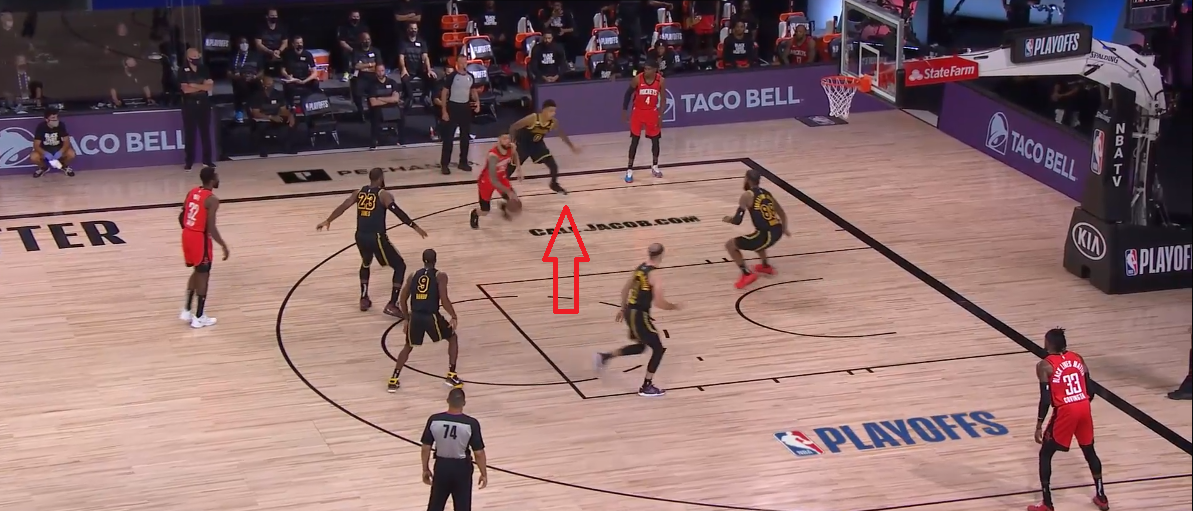

Here’s one from Game 2, when the Lakers trap with 14 on the shot clock:

(Austin Rivers lost the ball; it squirted to Covington, who heaved a hopeless 3-pointer as the shot clock expired.)

Danuel House Jr. flashes into the middle as an outlet, but the Lakers have been prepared for that cut. Their rotations underneath the trap have been on point — urgent, precise, decisive. Davis is everywhere. Kuzma is defending at a career-best level, and has been for most of the bubble. LeBron is in beast mode, rotating with ferocity and obliterating shots at the basket. (Seriously: I can almost hear and feel LeBron’s pounding, turbo footsteps through the television. My god.)

An interesting wrinkle from Game 3: The Lakers sent a lot of their traps — including in the first clip — from Harden’s left side. That might have been an accident. Harden operated a lot on the right side of the floor, leaving more defenders to his left. But it pushed Harden toward his weak hand, and the right sideline. He can still do damage there, of course. He quickly downloaded where the traps would originate, and drove the other direction:

The Rockets might adjust by sometimes clearing the right corner, so there are no help defenders nearby:

But there must be comfort in knowing where Harden is likely to go, and arranging the chess pieces so that path leads toward the sideline — shrinking his passing options.

When the Lakers’ trap did come from Harden’s right — and when he spotted it early — he rampaged left with his usual explosion:

(I’m not sure what JR Smith has done to earn these occasional bursts of playing time, but I guess he’s bound to hit a shot at some point.)

The Lakers have executed their traps well almost regardless of location. They doubled Harden 55 times combined over Games 2 and 3, and gave up only one point per possession after those traps, per tracking from ESPN Stats & Information — well below Houston’s overall average. They doubled Harden twice as often in the second half of Game 3 compared to the first 24 minutes, and held the Rockets to a measly 0.54 points per possession in that half, per ESPN Stats & Info. Tracking data from Second Spectrum is a little less sanguine about the Lakers’ trapping, but paints it as broadly effective.

Some of L.A.’s (rare) mistakes have been needless, overeager rotations well after the Lakers had trapped and reset their defense with the Rockets’ offense wheezing:

The trap (from the left again) works, and the initial rotations behind it are chef’s kiss gorgeous. You don’t need a second defender flying at Rivers when he’s well-covered in the midrange with five on the shot clock. Make him shoot a floater!

Please note Kuzma’s mini-rotation at the start of the Lakers’ scramble: He runs Rivers off the 3-point arc but does not chase him into the lane. He trusts Markieff Morris will be there, and U-turns to smother House in the right corner:

That is such a splendid little piece of defense. The Lakers’ after-trap rotations have been full of little goodies.

This is a more traditional trap — i.e., against a pick-and-roll — but Davis pulls almost the same rotation toggling between Westbrook and Covington:

Again: Davis has been everywhere.

Even so, sometimes Harden is just going to beat you. He’s that good, and when Westbrook is on the bench, the court is wide open:

The Lakers seem to know they can’t overdo this look; they saved it mostly for the second half in Game 3. Houston has some adjustments. The Rockets can set picks for Harden at half court, and give him a long runway. Harden attacking earlier, pre-trap, would help to the extent it’s possible to preempt the traps. Switching up the starting points of possessions — left, right, middle — might prevent the Lakers from getting into a rhythm.

If Houston is determined to run some pick-and-roll, it can vary Harden’s screener — Westbrook is useful in that role — and bust out some screen-the-screener actions to hold up the Lakers’ second defender.

The bigger issue is Westbrook’s up-and-down performance. He was one of Houston’s key trap-breakers in the regular season, cutting into open space and zooming for layups. Those layups are harder against the rim protection of James and Davis; Westbrook can’t force it when those two are girding to challenge him and kick-out passes are available. (Harden has also forced a few close shots when easy passes have been there.)

Houston is minus-19 in 18 minutes with Harden sitting — and Westbrook playing — over the past two games after winning those minutes in Game 1. Five of Westbrook’s 10 turnovers over those two games have come in those 18 minutes, and Westbrook turnovers — and misses at the basket — ignite the Lakers’ devastating fast-break machine.

(There is really no statistical evidence to back this up, but I get this occasional nagging feeling that if the Rockets ever miss the presence of a screen-and-dive center, it is during these Westbrook-only minutes. Westbrook fares well in a spread pick-and-roll attack, but the Rockets don’t have a screen-setter who presents any vertical threat. A lot of these Westbrook-only possessions consist of aimless passing along the perimeter before someone attacks a set defense one-on-one. Westbrook has a tougher time than Harden beating his own defenders, because they wait for him in the paint.)

The Lakers have also won (by a little) the Westbrook-Harden tandem minutes. Houston is plus-9 in 42 Harden-only minutes so far. There is a chunk late in the first and third quarters when Westbrook and LeBron rest at the same time — leaving Harden to face the LeBron-less Lakers. Watch those minutes. It will be hard for Houston to extend this series to six or seven games if they don’t win them.

House’s status for Game 4 is unclear, but it appears Covington is a go after his collision with Davis late in Game 3. The Rockets can’t afford to dig any deeper into their rotation. House’s absence cracked the door for more Ben McLemore minutes, and LeBron is hunting McLemore every chance he gets. If McLemore plays, it might have to be when LeBron rests. (Lakers fans would rightfully counter their team is missing Avery Bradley, an important starter.)

This Game 4 is a test of Houston’s will. The Rockets had chances to win Games 2 and 3, and lost both. That can be demoralizing. Will they wilt, or fight? Offense usually comes easy to the Rockets, but the Lakers are making them fight for everything.