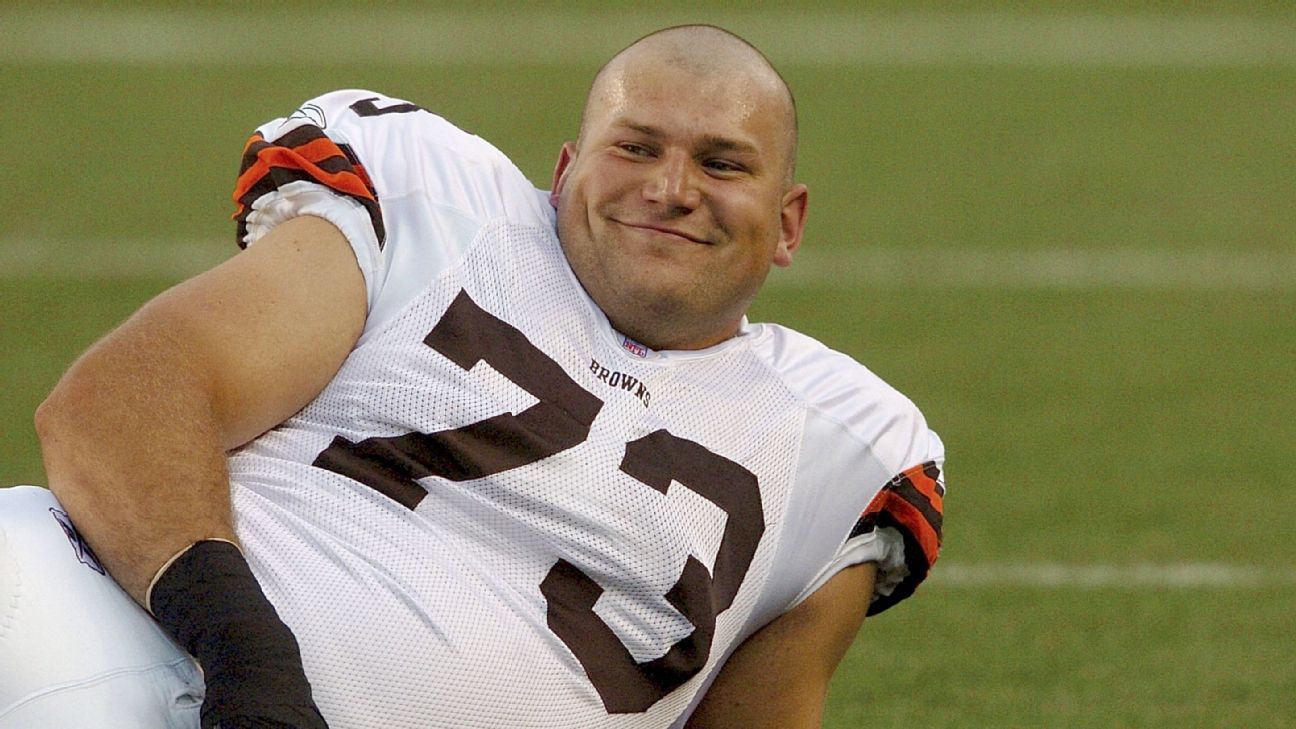

It’s 3 p.m., and Joe Thomas needs to eat. He’s driving with his family but is getting hungry. Is it really hunger? He doesn’t know. Throughout his entire NFL career as an offensive tackle with the Cleveland Browns, Thomas was conditioned to eat every two hours, because his job literally depended on it.

Thomas finds a McDonald’s on the GPS. It will be quick — just a bit of fuel between lunch and dinner. He orders two double cheeseburgers, two McChickens, a double quarter-pounder with cheese, one large order of fries and a large Dr. Pepper.

“Or another sugary drink,” he said recently. “Just to add 500 calories, the easy way.”

It wasn’t easy playing 10,000 consecutive snaps or fending off football’s most explosive pass-rushers. But it was just as hard for Thomas to maintain a 300-plus-pound frame. He had to consume an insatiable amount of food. Here’s a potential day in the life:

-

Think breakfast: four pieces of bacon, four sausage links, eight eggs, three pancakes and oatmeal with peanut butter, followed by a midmorning protein shake.

-

Lunch? Perhaps pasta, meatballs, cookies “and maybe a salad, great, whatever” from the team cafeteria.

-

For dinner, Thomas could devour an entire Detroit-style pizza himself, and then follow it with a sleeve of Thin Mint Girl Scout cookies and a bowl of ice cream. And finally, he would slurp down another protein shake before getting into bed.

“If I went two hours without eating, I literally would have cut your arm off and started eating it,” the former offensive lineman said. “I felt if I missed a meal after two hours, I was going to lose weight, and I was going to get in trouble. That was the mindset I had. We got weighed in on Mondays, and if I lost 5 pounds, my coach was going to give me hell.”

Eating in excess isn’t as glamorous as it sounds. In fact, laborious might be the better word. Throughout his career, Thomas woke up in the middle of the night and “crushed Tums.” He relied on pain medications and anti-inflammatories, and he had constant heartburn.

Then Thomas retired in 2018. “When you start eating and exercising like a normal human being,” Thomas said, “the health benefits are amazing.” He not only threw away the over-the-counter meds, but his skin cleared up, his yoga practice improved and he felt less bloated. Within six months, 60 pounds melted off from his 325-pound playing weight. By September 2019, TMZ picked up Thomas’ transformation, headlining an article: “Ex-NFL Fat Guy … LOOKS LIKE A CHISELED GREEK GOD.”

“I just had a great laugh,” Thomas said. “Isn’t that the typical lineman life? Eleven years in the NFL, and all I’m known as now is ex-NFL fat guy.”

Thomas is the latest example of an offensive lineman who, after retiring, recommitted to a normalized, healthy lifestyle after overeating and over-medicating during his NFL career. His journey might seem dramatic, but it’s not uncommon.

Longtime San Francisco 49ers tackle Joe Staley, who played in the most recent Super Bowl, has already donated five garbage bags of clothing and bought all new belts since his waist slimmed from 40 to 36 inches and he lost 50 pounds. Former Baltimore Ravens guard Marshal Yanda dropped 60 pounds in three months by going from 6,000 calories per day to 2,000. Nick Hardwick, Jeff Saturday, Alan Faneca and Matt Birk are all former big guys who now look like shells of themselves, which generated tabloid-like attention. The list continues on and on.

So how’d they pull it off? We interviewed nine retired offensive linemen about the lengths they went to in bulking up and their secrets to slimming down after hanging up their cleats. The players were candid about body image insecurities, outrageous diets, struggles with eating disorders and the short- and long-term health ramifications of maintaining their playing weights for so many years.

‘Training yourself to have an eating disorder’

Former offensive tackle Jordan Gross started 167 games over 11 seasons for the Carolina Panthers. He was a Pro Bowler three times, made the All-Rookie team in 2003 and started at right tackle for the Panthers in Super Bowl XXXVIII. Then he retired in 2014 and lost 70 pounds within six months.

“Fans know me more for losing weight than they do for anything I did in my entire career,” Gross said.

Although that kind of weight loss can be inspiring, it also points to the unhealthy relationship with food many offensive linemen develop, usually dating back to college. Faneca, a first-round draft pick of the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1998 who went on to 201 career starts with three teams, recalls his position coach at LSU chastising the entire offensive line once for “looking like a bunch of stuffed sausages,” challenging them to lose a pound a day. Later, he was told he had to gain more.

Thomas puts it bluntly: “You’re training yourself to have an eating disorder the way you view food when you’re in the NFL, and to try to deprogram that is a real challenge.” Body image and self-esteem issues can fester, as these athletes are told their worth can essentially be measured in calories and pounds.

“I always had this insecurity of being big when it came to dating life, talking to women and going out being a 300-pound man,” said former Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Atlanta Falcons center/guard Joe Hawley. “I didn’t want to be that big, but I had to because I loved football and that was my job.”

A lot of the weight is artificial to begin with. As Gross points out, “not many people are naturally that big,” but bulking up was essential to playing at the highest level and making millions of dollars. Gross, for example, ingested an enormous amount of protein each day while playing, including six pieces of bacon, six scrambled eggs, two 50-gram protein shakes, four hard-boiled eggs and two chicken breasts — all before 2 p.m. in the afternoon.

It’s a somewhat new phenomenon, according to Dr. Archie Roberts, a 1965 draft pick of the Jets who went on to become a cardiac surgeon. In 2001, Roberts co-founded the Living Heart Foundation, which annually conducts health screenings for retired football players. “In the 1990s, there was a push that suggested to some people that putting on more weight might make it a more effective and exciting game,” Roberts said. “Because the bigger offensive linemen could hold off the defensive rush for a longer time so that the quarterback could throw the ball down the field, leading to more spectacular passing plays.”

Playing weights began ballooning across the league, especially on the line. According to Elias Sports Bureau research, the average weight of starting offensive linemen was 254.3 pounds in 1970. It jumped to 276.9 by 1990, but the largest increase in poundage would come in the following 10 years. A decade later, the average O-line starter checked in at 309.4 pounds. Today the number stands at 315, more than 60 pounds heavier than 50 years ago.

Hawley typically played between 295 and 300 pounds, but during his fifth year in the league, he adopted the paleo diet and ate clean. He lost 10 to 15 pounds and played the following season at 285. “It was hard to keep weight on eating clean like that, but I felt so much better,” Hawley said. “I had so much energy; I wasn’t as lethargic.”

Then, he re-signed in Tampa Bay.

“Because I was getting pushed around a little bit playing on the offensive line that way, they told me I needed to gain weight,” Hawley said. “So I went to a more unhealthy diet, which made me feel, well, not as good. But it’s what I had to do to play.”

“Being skinny as a lineman wouldn’t be helpful, because you would have to create more force to stop those big guys,” Thomas said. “Inertia becomes an issue. I’m a big, fat guy, you’re running at me, you don’t have to create as much force because I’m just heavier, fatter and have more mass.”

The benefits of slimming down

Although that mass helps on the field, health complications can follow. In May, USA Today ran an entire column wondering if offensive linemen were more susceptible to severe complications from COVID-19 because of their size. Roberts warns that massive weight gain can also lead to obesity. “Which then affects their heart, lungs, kidney and their minds,” Roberts said. “It’s not proven, but it also may be associated with Alzheimer’s disease and possibly traumatic brain injury.”

Once playing careers wind down, many players must assess whether it’s worth it to carry the extra pounds. Many have decided to downsize.

Faneca, the longtime Steelers guard, remembers the day he hit a milestone of losing 30 pounds. He was playing on the floor with his daughter and he got up without having to “do the old-man grunt.” “I just stood up, no problem,” Faneca said. “And I was like, ‘Wow, this is nice.'”

Thomas said when he was 300 pounds, his body would ache if he had to stand for a few minutes. Gross said he hated the sweating. “I would just sweat profusely all the time,” he lamented. “My wife would have hypothermia from me having the room so cold all the time.”

Hardwick, a center with the then-San Diego Chargers who maxed out at 308, said his initial motivation to lose weight was to relieve pressure from his body. (According to the April issue of the Harvard Medical School newsletter, each additional pound you carry places about 4 pounds of stress on the knee joints.)

“But then there’s this material aspect to it,” Hardwick said. “You want to be able to wear cooler clothes, and go into stores and start shopping off the rack. And that’s alluring for a while. Then that wears off, and you settle in, and people stop freaking out every time they see you. And you just become comfortable once again in your own skin.”

Staley, albeit sheepishly, admits he likes the fact that his muscles are getting defined.

“As an offensive lineman, you’re always known as this big, humongous, unathletic blob,” Staley said. “Offensive linemen get casted in a movie, and they’re always 500 pounds. Then you get the opportunity to be healthy again, and all of the effort you used to put into football, you put into that. It gives you a focus once you retire. It’s a little bit vain, but I’m starting to see abs that I’ve always wanted. And it’s kind of exciting.”

Oh, the things we eat …

There are two types of offensive linemen: those who must artificially add the pounds on, and those who are naturally big.

“I’m the latter,” said Damien Woody, a longtime NFL lineman and current ESPN analyst. “I could literally breathe and inhale and gain 5 pounds.” During a summer growth spurt after his sophomore year of high school, Woody grew 6 inches and gained 70 pounds. By the time he got to Boston College, he already weighed 300. “It was never a problem for me to put weight on,” he said.

The other group? Gaining weight can become an all-consuming sport, which often begins in the collegiate years. Consider Hardwick, who wrestled in the 171-pound weight class in high school. He enrolled at Purdue on a ROTC scholarship, got a tryout for the football team and ballooned to 295 by slathering 2 pounds of ground beef on multiple tortillas at dinner. Hardwick also downed a 600- or 700-calorie protein shake before bed and set his alarm to drink a similar one at 3 a.m.

At this year’s NFL combine, Ben Bartch was fetishized after talking about his go-to smoothie: seven scrambled eggs, “a big tub” of cottage cheese, grits, peanut butter, a banana and Gatorade. A daily dose of that concoction added 59 pounds to Bartch’s 6-foot-6 frame, helping him morph from a third-string Division III tight end at St. John’s (Minnesota) to a fourth-round pick of the Jacksonville Jaguars as an offensive lineman.

“I would just throw it all in and then plug my nose,” Bartch said. “In the dark. I would gag sometimes. That’s what you have to do sometimes.”

Chris Bober, a former New York Giants and Kansas City Chiefs lineman, showed up at the University of Nebraska-Omaha at 225 pounds, which was too small. He ate everything he could get his hands on, which was difficult as a college student “who was pretty broke.” It was especially challenging over the summers, when he inherently burned calories at his construction job. If Bober went to Subway, he wouldn’t just buy one foot-long sub — he’d get two. At Taco John’s, his order was a 12-pack of tacos and a pound of potato oles, which adds up to a nearly 5,000-calorie lunch.

When Thomas was at Wisconsin, any player trying to gain weight could grab a 10-ounce to-go carton of heavy whipping cream with added sugars and whey protein after a workout. He surmises the dairy-forward drink went for about 1,000 calories a pop — and he chased it with a 50-gram protein shake on his way to class.

Like Hardwick, Staley — who went from 215 pounds to 295 at Central Michigan, as he transitioned from tight end to the offensive line — used to set an alarm for himself every day at 2 a.m. “I had these premade weight-gainer shakes; they were probably 2,000 calories each,” Staley said. “I’d wake myself up in the middle of the night, down that, go back to bed.”

Although Staley worked with his college strength coach to make sure he was putting on “good weight” — gaining muscle without unnecessary body fat — the unnatural eating habits took a toll. “I was bloated for four years straight,” Staley said. “You know when you overeat after a really nice dinner at an Italian restaurant, you just eat all these courses and leave feeling gross? That’s how I felt the entire time in college.”

Staley no longer fit into the clothes he arrived at Central Michigan with but couldn’t afford to buy new ones, so he was constantly borrowing from teammates. Most offensive linemen admit they pretty much lived in team-issued sweats. “I’m lucky, in the late 1990s, early 2000s, everything baggy was in style,” Gross said. “So from 250 to 300, it wasn’t a massive wardrobe change. The waist got big, but elastic drawstrings were my best friend.”

The habits continue in the NFL. Many older players credit the 2011 collective bargaining agreement, which banned training camp two-a-days, as a turning point. Before then, it felt like their college days. “If I was doing two-a-days, in the summer in South Carolina, going up against Julius Peppers, I was for sure burning 10,000 calories,” Gross said.

So at the end of each day in training camp at Wofford College, Gross counted to 15 one-thousands on the soft-serve machine, then blended that with four cups of whole milk, plus three homemade chocolate cookies (which Gross believes were about 850 calories each) and Hershey’s chocolate syrup. “That’s all inflammatory foods, like sugar and dairy,” he said, “I’m not going to say it’s horrible; it was pretty awesome to eat that stuff. But you’re putting so much demand on your digestive system. I always had gas. I always had to use the bathroom. I was bloated because I was so full all the time.”

Striving to be the biggest loser

There’s a common refrain among offensive linemen: If you don’t lose weight in your first year out of the league, you’re probably not going to lose it.

Four years after retiring, Woody weighed 388 pounds and agreed to appear on NBC’s “The Biggest Loser.” Instead of heavy lifting and concentrating on explosive bursts, Woody was asked to do longer cardio and train for endurance. “It was totally different from what I had learned to do and had trained to do my entire life,” Woody said. “And it was hard. Like, man, it was really tough.”

Woody lost 100 pounds on the show — then gained it all back.

So he just accepted his weight, until this past year, when the 42-year-old renovated his basement into an exercise room. “I wanted to lose weight the right way,” Woody said. “In a sustainable way.”

Woody lured in his wife and kids to join his mission. On Sunday nights, they meal prep. And every day Woody goes down to the basement to stay active. His prefers the Peloton bike — “I hit that hard,” he said — but also uses the row machine, and does “all different types of exercises so I don’t get bored.” While he still lifts weights, he focuses on lighter options and higher reps. “I’m not putting any weight on my back anymore; I’m not lifting excessive weight to potentially hurt myself,” Woody said. “Because that’s not the point anymore.”

On June 14, Woody tweeted that he was down 50 pounds since March 23 “and my joints are already jumping for joy.”

It isn’t easy. And for many years, players have felt like they’re on their own in their weight-loss journey.

“The NFL doesn’t give you any guidance on how to do it,” Bober said. “They’re just like, ‘OK, see ya!’ You need to take it upon yourself to figure it out. And as I’ve gotten older and older, I’ve noticed it does become more and more difficult to manage if you haven’t lost it right away.”

Shortly after the last CBA in 2011, the NFL Players Association launched “The Trust,” which interim executive director Kelly Mehrtens describes as a VIP concierge service of benefits players can take advantage of as they transition outside of the league. As part of a holistic approach, the Trust invites players to Exos (where they can train, get physical therapy and undergo a nutrition consultation), offers them YMCA memberships and arranges physicals and consultations with specialists at hospitals across the country.

The Trust, Mehrtens explains, is all about figuring out why certain guys transition to their post-playing lives more successfully than others, and how they could help bridge the gap. “These are earned benefits,” Mehrtens said. “So we want to make sure guys take advantage of something they’ve already earned.”

Dr. Roberts’ Living Heart Foundation, a partner of the NFLPA, does health screenings for former players three times per year. Anyone with a BMI of 35 or over is invited to join a six-month program called The Biggest Loser (although this one isn’t televised). So far, roughly 50 players have gone through it. Most are in their 40s, with the oldest participant 80 years old. “It just shows it’s never too late to find motivation to reach your goals,” lead trainer Erik Beshore said.

Beshore said most who enrolled in The Biggest Loser program are diabetic or pre-diabetic. However, after six months, as they commit to sustainable lifestyle changes, many have gone off their insulin, eliminated their blood pressure medication, gotten better sleep and reported overall better moods.

“It’s amazing how many of them can lose the weight all these years later,” Roberts said. “But in terms of if they can reverse the damage that may have occurred in the interim period form when they played football at large size to years later, it’s hard to quantitate because we don’t have long-term data yet.”

Living the healthy lifestyle

To slim down, Staley cut out most carbs, besides vegetables. He purged his house of his favorite vice, chips and salsa, and now snacks on raw broccoli and Bitchin’ Sauce — an almond-based vegan dip. Staley said he now eats with purpose and moderation. “In the NFL, I always ate when I was hungry and whatever was available,” he said. “If it was salmon, great. If it was frozen pizza, I’d eat that too.”

Hawley, who retired in 2018, donated most of his material possessions to charity and has been living out of a van and Airbnb’s across the country. He said it was all about reconditioning his brain to eat only until he feels full, and not eating until he can’t eat anymore. Intermittent fasting has been a huge tool for the 6-foot-3 Hawley, who is down 60 pounds to 240. He rarely eats breakfast and tries to do one 24-hour fast per week — eating dinner at 6 or 7 p.m., and then not eating at all until 6 or 7 p.m. the following night. Sometimes he even challenges himself to a 36-hour fast.

Hawley has connected with other ex-big guys, such as Hardwick, whom he met at “Bridge to Success,” a NFL-run transition program for retired players.

“But it’s not as big of a community as I would like,” Hawley said. “I’m actually working on creating an online community for guys. That’s one thing I’ve been missing. I went through my whole life being part of a locker room with a team, and then you get into the real world at 30, and nobody really knows what that experience is like.”

Hardwick said he’s working on an e-book with a blueprint of his diet plan for people who want to lose weight quickly and keep it off.

Many players interviewed for this story said while they do feel better and like the way they look, rapid weight loss has led to unsightly stretch marks and excess, saggy skin (which one player, wishing to stay anonymous, said he had cosmetically removed). Hardwick and Gross also warn of something that happened to them: They got so obsessed with losing the weight that it went too far.

Hardwick remembers weighing himself after a hot yoga class in January 2015. The scale read 202 pounds. “Great,” he thought to himself. “Another 3 pounds, and it will be 199.” But then he got a glance of his profile in the mirror, and he didn’t recognize himself.

“If the apocalypse came, there was no way I could defend me or my family,” he said. Hardwick went home and started binge eating to overcorrect. He has hovered between 220 and 230 since, which he thinks is a healthy weight for him.

Gross experimented for a while. He was vegetarian for a year and then tried the paleo diet. “You don’t have any wiggle room when you’re playing — you just have to eat to keep the weight on,” he said. “So I thought it was exciting to try different things.” Once Gross got down to 250, he noticed an immense pain relief in his feet and ankles, which were swollen his last few years in the league — but due to weight, not injury.

When Gross began his transformation, he went to Old Navy and bought three pairs of shorts and two polo shirts. He didn’t know where his weight loss would lead him, and he didn’t want to waste money. Gross got all the way down to 225, but restricting himself to under 2,500 calories a day didn’t feel like a sustainable lifestyle. “That was too much,” he said. As he gets ready to turn 40 this summer, Gross eats about 3,200 calories a day and is back to lifting weights. He now happily hovers around 240 pounds.

As for Thomas? As his career wound down, he began consulting with Katy Meassick, the Browns’ nutritionist, who began educating him on healthier habits. They came up with a post-retirement plan, which Thomas describes as “low-carb or keto diet, with intermittent fasting.” He added swimming and biking as cardio, along with yoga.

Thomas, too, had to recondition his brain to stop eating when he was full. Throughout his football career, he had taught his subconscious to go beyond that point and keep stuffing his face with family-size McDonald’s orders and sugary drinks. It’s a new kind of discipline. Now every Monday, Thomas and his wife, Annie, will try to fast for 24 hours. Because of his previous line of work, it’s not such a hard transition.

“As an offensive lineman, you just do the grunt work forever and you do the crap nobody wants to do — our position is the Mushroom Club. We’re used to being s— on a truck in a dark room, and everyone expects us to go out and perform for no glory whatsoever,” Thomas said.

“And you almost miss that misery. It’s almost a weird thing to say, but getting into the fasting world and trying to discipline yourself and do something that is hard, in a weird, sick way, [that’s something] I think a lot of offensive linemen get.”