Aryna Sabalenka, the eventual 2024 US Open champion, took the court for her third-round match against Ekaterina Alexandrova on Arthur Ashe Stadium at 12:08 a.m. It was the latest-ever start for a match at the US Open.

Two days later, in the round of 16, Zheng Qinwen and Donna Vekic left the court on Ashe at 2:15 a.m. in what was the latest finish for a women’s match at the tournament.

Those late starts have a direct effect on the possibility of being injured, according to a recent report compiled by the Professional Tennis Players Association (PTPA) and shared with ESPN. It indicated a sizable increase in injury risk for players participating in night matches compared to those played earlier in the day.

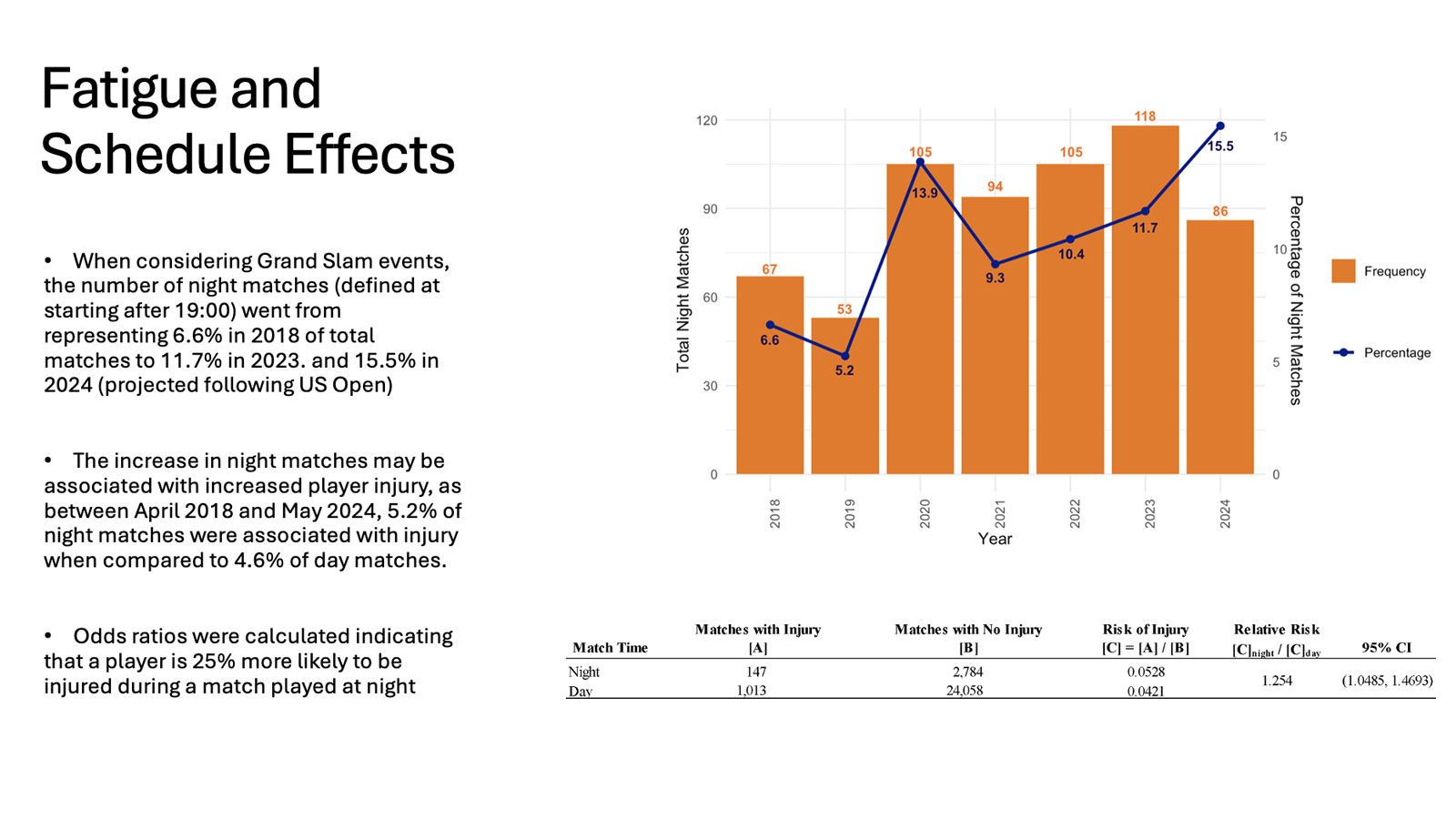

According to the PTPA report, which used data from Grand Slam events taking place from April 2018 through May 2024, as the percentage of night matches (starting after 7 p.m.) increased, the injury rate also increased from 4.6% to 5.2%.

PTPA medical director Dr. Robby Sikka, who led the team that conducted the data analysis, said odds ratios were calculated that indicated a player is 25% more likely to be injured during a match played at night.

And yet, night matches at major tournaments remain on the rise — going from a little under 7% of matches to more than 11%, according to the study. That number is expected to increase to more than 15% once data from this year’s US Open is included, Sikka told ESPN.

Players have routinely expressed concerns about how playing later matches impacts their health and performance.

Coco Gauff, the 2023 US Open champion and current world No. 6, called post-midnight finishes “not healthy” at the French Open in June. Novak Djokovic, the 24-time major champion and co-founder of the PTPA, said he struggles with late-night matches at this stage of his career.

“I don’t think that aging helps really staying so late and playing very late,” Djokovic, 37, said after his first-round match at the US Open, which was the second night match on Ashe. “I can feel, you know, my batteries are low now. I’m shutting down.”

Djokovic’s third-round match at the French Open this summer — a five-set win over Lorenzo Musetti — ended at 3:06 a.m. and was the latest finish in tournament history. He tore the meniscus in his right knee during his next match and withdrew ahead of the quarterfinals and underwent surgery.

Daria Kasatkina, currently No. 13 in the world, told ESPN that the night doesn’t end when the match is over.

“You cannot go to sleep straight away … you have some interviews straight after, you then have to do stretch, ice bath recovery, eat, then mandatory media, [such as] a press conference or whatever you will be requested to do,” she said.

Kasatkina pointed out that each athlete has his or her own recovery/rehab routine. The athlete then has to make the trip back to the hotel which, depending on the tournament, can take an additional 30 minutes or more.

Kasatkina has experience with late matches. In August 2023, she played Elena Rybakina in a Canadian Open match that started at 11:27 p.m. They finished nearly 3½ hours later at 2:57 a.m.

“You’re destroyed,” Kasatkina said of late matches. “You spend a lot of emotion, a lot of physical energy.”

To compound the effect, scheduling does not always take when a previous match ends into account.

“You might play first the day after you play last,” Kasatkina said.

PTPA executive director Ahmad Nassar noted the athletes’ frustration around increasingly late start times and turned to Sikka to capture their concerns with objective data.

“[Dr. Sikka] was a guy that we knew through baseball and football and basketball and we said, ‘Hey, would you be interested in kind of looking at some of these issues and working with us on this?'”

The results, while not particularly surprising, provided quantifiable metrics to support what the athletes were reporting from personal experience.

“It’s one thing to grumble, ‘I don’t like late-night matches,’ Nassar said. “It’s much different to say, here’s some real data, 25% greater chance of injury. … And then, you know, you kind of go to what do you do about it?”

The ATP, which runs men’s tennis worldwide, declined to comment for this story. A representative shared the organization’s joint press release with the WTA from January explaining changes both tours had made to alleviate late-night matches.

In the release, which acknowledged how such late starts and finishes were “negatively impacting players and fans,” it stated various regulations for tour events, including the banning of matches starting after 11 p.m. (unless approved by a tour supervisor), the moving of matches to an alternate court if not started by 10:30 p.m. and the disallowing of night sessions to begin after 7:30 p.m. ET.

Those changes went into effect at the start of the 2024 season. Amy Binder, the WTA’s senior vice president of global communications, noted that as of Sept. 10, there has been just one instance when a match at a WTA event started after 11 p.m. since the change went into effect and it was “in full consultation and agreement with the competing athletes.”

The four Grand Slam events operate independently from the tours, however, and do not need to abide by the same regulations. Wimbledon has had a curfew of 11 p.m. in place since it added the roof to Centre Court in 2009 in an agreement with local officials. The US Open implemented its own policy related to night matches this year. If the second night match on Arthur Ashe Stadium or Louis Armstrong Stadium had not started by 11:15 p.m., the match could have been moved to another court.

“The referee will have the discretion to move the match,” tournament director Stacey Allaster said in a pre-event media briefing in August. “That’s going to depend on many variables, like do we have the broadcast team ready, do we have a ball crew, so forth.”

But Sabalenka and Alexandrova took the court well after 11:15 p.m. Nassar said both players were consulted and said they wanted to remain on Ashe. But Nassar doesn’t believe it should have come down to the players making the call.

“This might not be the most popular opinion, but you don’t ask a player in the NFL, ‘Oh, how do you feel? You want to stick it out even if we think you have a concussion?’ No, man, the rule is you gotta go,” Nassar said. “That’s part of changing the culture and I know players want to play on certain courts at certain tournaments, that’s natural. But [we’re at] the point where the culture is actually dangerous. Not just annoying, but dangerous.”

Player concerns are not strictly limited to late-night match starts. Issues such as mandatory tournament demands, the transition of several of the 1000-level events from one week to two, and the number of matches being played are all areas of focus.

“The tournaments are longer, the draws are bigger. Recovery time is less,” said Kasatkina.

“Plus the travel is increasing because we have more tournaments. We have to travel from one coast to another, from one time zone to another. Now we don’t have much time for preparations. We cannot do much practice blocks. We can’t get enough rest. I mean, you can, but you have to sacrifice some of the tournaments. Like you always have to make a choice.”

There are also the surface changes that accompany different venues factoring into the equation for players.

Hubert Hurkacz, currently ranked No. 8, said constantly changing surfaces is tough on players. He noted that was especially true this year with the addition of the Olympic Games, played on clay, following the end of the grass season and right before the start of the summer hard-court portion of the schedule.

“Let’s say you’re going to the Olympics, you’re practicing for a week on clay or getting ready, your body’s ready to go,” Hurkacz told ESPN. “Then you play a good tournament and then the next day you’re on the flight say to Montreal, and you’re playing on a different surface, different conditions on hard court, [where] the sliding is so much different. … Ultimately it’s really difficult without having proper preparation.”

Sikka notes the PTPA is looking to learn from other sports leagues and their approaches to data analytics as a means of effecting change.

“How did the NFL approach their concussion data?” he said. “If baseball has all these arm and elbow injuries and they’re worried about pitch counts, should we have a serve count?”

He noted the power era of tennis, when higher spin rates and serve velocities appear to correlate with chances of winning. But is there an injury cost? The answer, Sikka believes, lies in the data.

“No data is perfect,” he said. “But these are trends that are pretty indisputable. And now there’s a measurable thing that if we want to intervene, we’ve got a baseline for comparison.”

Sikka also believes the solutions lie in the PTPA, the tours and the Slams working together towards a common goal of optimizing player health and performance.

“We’re not here to put people down,” Sikka said, “We’re not here to rabble-rouse. We’re here to improve the quality of care for a population.”