MY LATE FATHER bought me a Joe Montana jersey when I was a boy. Home red with white stripes. I don’t remember when he gave it to me, or why, but I’ll never forget the way the mesh sleeves felt against my arms. The last time I visited my mom, I looked for it in her closets. She said it’d been put away somewhere. On trips home I half expect to still see my dad sitting at the head of the long dining room table, papers strewn, working on a brief or a closing argument. He was an ambitious man who had played quarterback in high school and loved what that detail told people about him — here, friends, was a leader, a winner, a person his peers trusted most in moments when they needed something extraordinary. Lots of young men like my father play high school quarterback, roughly 16,000 starters in America each year. Only 746 men have ever played the position in the NFL and just 35 of them are in the Hall of Fame. What my father knew when he gave me that jersey was that only one of them was Joe Montana.

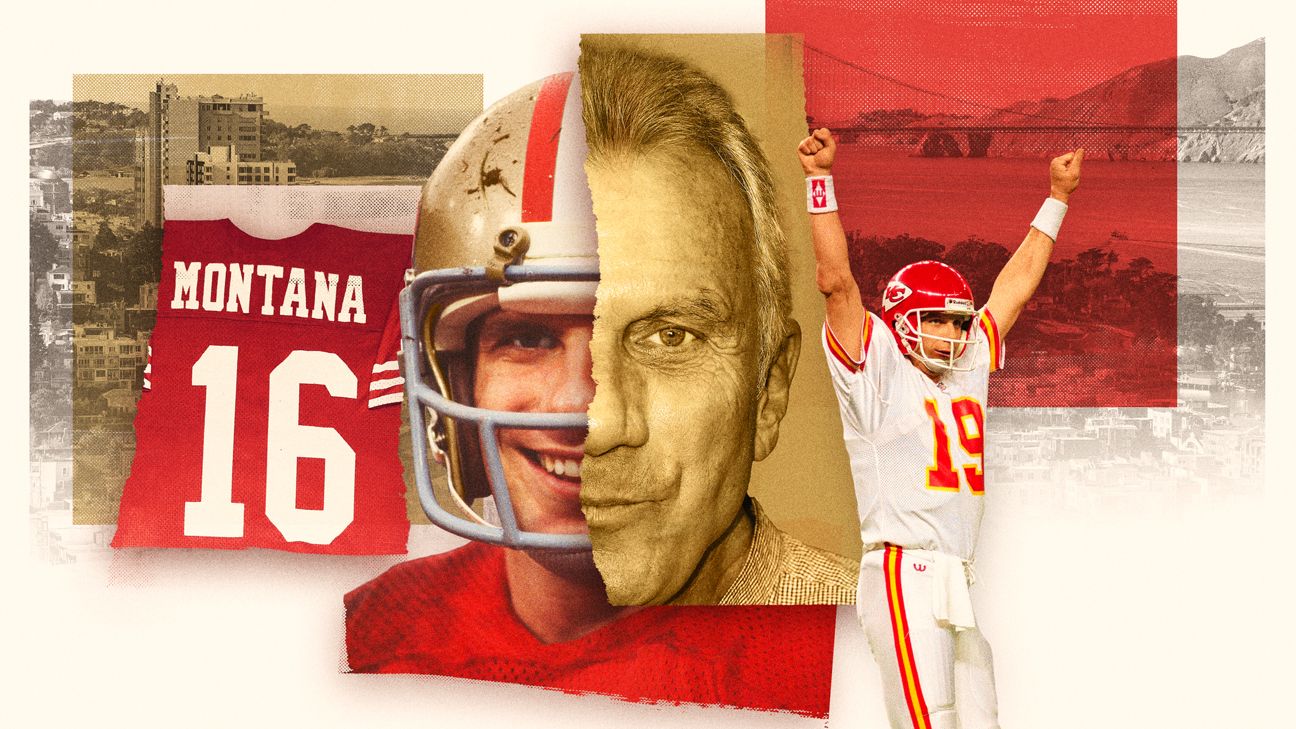

Tom Brady Sr., bought his son, Tommy, a No. 16 jersey once, too. They sat in the upper deck of Candlestick Park together on Sundays. They looked down onto the field and dreamed. Tommy enrolled as a freshman at Michigan the year Joe Montana retired from football. Forced out of the game by injuries, Montana left as the unquestioned greatest of all time. His reputation had been bought in blood and preceded him like rose petals. Everybody knew. But over time the boy who sat in the upper deck idolizing Montana delivered on his own dreams and built his own reputation. Here, friends, was a threat. The boy, of course, went on to win his own Super Bowls. A fourth, a fifth, a sixth and a seventh. Parents now buy their children No. 12 jerseys because there can only be one unquestioned greatest of all time. No. 16 is no longer what it once was. Joe Montana now must be something else.

“Does it bug you?” I ask.

“Not really,” Montana says.

He sits at his desk and taps his fingers on his thumb, counting, keeping track of odds and evens. Placid on the surface, churning beneath the waves.

“You start thinking,” he says, his voice trailing off.

“I wish … “

MONTANA COMES INTO his San Francisco office waving around a box of doughnuts he picked up at a hole in the wall he loves. He’s got on Chuck Taylors and a fly-fishing T-shirt.

“… so chocolate, regular and maple crumb,” he says.

It’s a big day for his venture capital firm and nothing spreads cheer like an open box of doughnuts. He looks inside and chooses.

“Maple.”

It’s a tiny office, stark, with mostly empty shelves, a place rigged for work. There’s a signed John Candy photo a client sent him — a nod to a famous moment in his old life — leaning against the wall. Four Super Bowl rings buy him very little this morning on the last day of the Y Combinator — a kind of blind date Silicon Valley prom that puts a highly curated group of 400 founders in front of a thousand or so top investors. Each founder gets about a minute and a half to two minutes to pitch investors like Joe. A company founder promises to, say, fully automate the packing process, reducing manual labor from days to hours, a market opportunity of $10 billion. You can hear the nerves in their voices as they talk into their webcam. Some clearly haven’t slept in days. Without considering my audience — 11 plays, 92 yards, 2 minutes, 46 seconds — I marvel at the insanity of having your entire future determined in an instant.

“I know,” Montana laughs.

His company, Liquid 2, consists of multiple funds. He’s got two founding partners, Michael Ma and Mike Miller. Recently he brought in his son, Nate, along with a former Notre Dame teammate of Nate’s named Matt Mulvey — which makes three Fighting Irish quarterbacks. His daughter, Elizabeth, runs the office with a velvet fist. Their first fund is a big success and contains 21 “unicorns,” which is slang for a billion-dollar company. They’re headed toward 10 times the original investment. Montana, it turns out, is good at this.

“You just look at the teams and the relationship of the founders,” he says. “How they get along? How long they’ve known each other?”

We take the doughnuts and his computer down the hall to a conference room. Nate and Matt are already there.

“So that guy hasn’t responded to us,” Matt tells him.

That guy, Amer Baroudi, is a Rhodes scholar and a founder of a company they love. It’s always a dance. Much bigger investors than Liquid 2 are also after these ideas. The guys huddle and decide that No. 16 should write him directly, politely, and tell him they’re interested and would love to connect. As he does that, the companies keep presenting new ideas. Microloans in Mexico. A digital bank for African truckers. They’re all on their laptops and their phones while the presentations happen on a big screen at the end of the room. His partners keep in touch on a Slack channel. Joe’s handle is JCM.

One founder developed weapons for the Department of Defense. Another worked for NASA. Every other one it seems went to MIT or Cal Tech. They worked for McKinsey and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. One idea after another, pitched by passionate, interesting people. I can feel Joe vibrating with energy and excitement. He leans over Nate’s shoulder with his hand on his back. He rubs his nose, then his chin, then moves his hand over his mouth in concentration. His eyes narrow.

He checks his phone and smiles.

“Amer,” he says.

MONTANA’S CAR IS parked a block up and we get to an intersection just as the light is changing. A work truck lurches into the intersection and then stops. The driver rolls down the window and sticks out his head. He nods at me.

“I might hit you … ” he says.

He looks at Joe and breaks into a grin.

“… but I won’t hit him.”

The Montanas live in a city where it’s still common for No. 16 to be the only Niners jersey framed on barroom walls. He’s beloved in the 7-mile by 7-mile square where he built his legend and where he and his wife, Jennifer, built their life. The Montana home is just steps from where Joe proposed nearly 40 years ago. Friends joke about how grossly romantic they are, always holding hands, still taking baths together, and one friend said she can actually see Joe’s body language change when Jennifer enters a room, as if he knows it’s OK to relax. In the car he’s always got his hand on her knee. Once during a game he looked at the sideline phone that connected him to the coaches upstairs. He picked it up and, just to see, pressed nine. To his shock he got an outside line and looking around, he dialed Jennifer to say hello. She’s always been able to level him out. “The only one that cools him down — and he doesn’t go full Super Bowl mode — is if my mom’s there,” Nick Montana says.

From one of their roof decks in the Marina district, they can see both bridges, Alcatraz and the old wharfs. After moving around a lot since football ended they’ve returned here. They know their neighbors. The kid whose family shares a fence line once accidentally threw his USC branded football over that fence. It came hurtling back — with a note written on the ball that said, “Go Notre Dame. Joe Montana No. 3.” It’s a beautiful place to call home. Their lives revolve around the kitchen. Jennifer and the two girls make salads. Joe mans the wood burning oven or the grill. The two boys — “they’re useless,” Jennifer jokes — bring wine or lug stuff around. Everyone does the dishes.

“They’re very Italian,” family friend Lori Puccinelli-Stern says. “A lot of everything they do is around a big table with family and friends and them cooking. Cooking together. Eating together.”

Before they died Joe’s parents always lived near them. When he retired, Grammy and Pappy moved up to Napa Valley, too. Pappy coached the boys’ and girls’ youth sports teams. Most Sundays after football ended they would all gather for huge family dinners. Grammy would make her famous ravioli. Jennifer makes it now.

The neighborhood between his office and his home is North Beach, the old San Francisco Italian enclave, and one afternoon he drove me down the main boulevard. We passed Francis Ford Coppola’s office and the famous City Lights bookstore, rolling through the trattorias and corner bars of North Beach. Up the hill to the left is the street where Joe DiMaggio grew up. DiMaggio’s father, Giuseppe, kept his small fishing boat at the marina where the Montanas now live. Every day, no matter how dark and menacing the bay, Giuseppe DiMaggio awoke before the sun and steered his boat off the coast of California. He gave his son an American first name and wanted for him an ambitious American life. Joltin’ Joe realized every dream his dad dreamed but emerged from the struggle a bitter man prone to black moods as rough and unpredictable as his father’s workplace.

Bitterness is such a common affliction of once-great athletes that it’s only noteworthy when absent. Ted Williams burned every family photo. Michael Jordan kept trying to get down to his playing weight of 218 years after his retirement. The story goes that Mickey Mantle used to go sit in his car during rainstorms, drunk and crying, because the water hitting the roof sounded like cheers. Joe and Jennifer’s front door is just around the corner, maybe a three-minute walk, from the house DiMaggio bought for his parents with his first big check in 1937 and where he moved when he retired from baseball in 1951. He and Marilyn Monroe spent their wedding night there. The Marina remained full of memories for him. DiMaggio loved to sit alone there and stare out to sea as if looking for a returning vessel. The two Joes knew each other in the 1980s but weren’t friends. DiMaggio was much closer to Joe’s mother, who worked as a teller at the branch where the Yankee legend banked.

“Why did your mom have a job?” I ask as we drive down Columbus Avenue.

Joe smiles. His mom was one of a kind. When he was a kid she bleached his football pants at night so he’d always look the best. She found the job herself.

“She got tired of just hanging around,” he says.

THE FIRST JOSEPH Montana, Joe’s great-grandfather, was born Guiseppi Montani in 1865 in a mountain village in the Piedmont region of Italy. The Montanis had been in their town for generations when Guiseppi left everything behind. He carried only his name, which described the world he’d left behind. In America, the family changed the “i” to an “a” and were now the Montanas of Monongahela City, Pennsylvania, putting down roots in a sooty town with physical but stable jobs. All the men worked in coal and steel. They raised huge American families. Guiseppi died in his home on Main Street and left behind 16 grandchildren, one of them Joe’s dad. Two of Joe’s grandparents were born in Italy. All four were Italian. His maternal grandmother, who went to Mass every day and spent the rest of her time sewing, always told him stories about her home.

“My grandmother came over when she was 12 or 13,” he says.

“You’ve been to the town?”

“Yeah,” he says, “but I’m trying to get back.”

He regrets not learning Italian as a child when he moved around the ankles and knees of his relatives who parlo’d and prego’d away in the kitchen, a place where flour and water became dough. A few times as an adult he’s tried to learn. Taken classes. Bought Rosetta Stone. It just never stuck. Even as he reaches an age where learning new things can hang just out of reach, he remains happiest when he’s curious and engaged. It’s clear his kitchen in San Francisco is a place where he engages with his ancestors. The old ways matter to him. Once during a commercial shoot at Ellis Island he slipped away to find his family’s records. I can picture him in those archives, a public figure on the outside but inside still the boy trying to understand where he came from, why he wanted what he wanted, why he feared what he feared. He inherited his ambition from his father, who inherited it from his grandfather, who pulled up stakes and wrote a new story on top of a rich vein of coal. His inheritance is both a charge and a burden. He’s not standing on the shoulders of his ancestors so much as he is bringing them along for the ride — chasing a dream so big that reaching it would make all their dreams come true as well. His inheritance demanded that he strive for the mountaintop alone — Guiseppi Montani — and his birthright promises that he be permitted to enjoy reflecting on that climb.

His grandmother refused her wealthy grandson’s offers of an all-paid return trip to her village, he says. She wanted her memories of the past to remain uncomplicated. Hers was a generation that wanted to keep moving forward, to resist the pull of some older and more limiting story of who they were or what they were capable of becoming. Hers was a devout act of forgetting. Joe understands. He doesn’t go home anymore, either.

His high school football coach, Chuck Abramski, hated him. Really he hated Joe’s father, who wanted to be the primary voice in his talented son’s ear, but he took it out on Joe. When Montana refused to quit basketball to join Abramski’s offseason workout program, Abramski didn’t start him for three games until he looked dumb keeping a phenom on the sideline. When Joey Montana became the Greatest of All Time, his success turned Abramski’s coaching career into footnote, a parable about a small man not ready for his moment in the sun. That ate at him. His tombstone says Coach. It was his entire identity. He was a proud man who, when faced with the biggest decision of his professional life, made the wrong one, out of stubbornness and pride, and then doubled down on his mistake over and over again. Every few years he would get quoted in a Montana profile. The last time came in the days before Montana’s fourth and final Super Bowl, which he would win.

“A lot of people in Monongahela hate Joe,” Abramski told Sports Illustrated.

He kept going.

“If I was in a war,” he said, “I wouldn’t want Joe on my side. His dad would have to carry his gun for him.”

“I called him about it,” Montana said at the time. “Three times now, I’ve seen those Abramski quotes around Super Bowl time, about why people hate me. I asked him why he kept saying those things, and he said, ‘Well, you never sent me a picture, and you sent one to Jeff Petrucci, the quarterback coach.’ I said, ‘You never asked.’ I mean, I don’t send my picture around everywhere. We ended up yelling at each other. We had to put our wives on.”

Montana showed grace the coach couldn’t really bring himself to show. He invited Abramski to Canton, Ohio, for his Hall of Fame induction.

“Joe was very gracious to my dad,” daughter Marian Fiscus says.

Abramski died almost five years ago.

Montana doesn’t feel nostalgic about his hometown. He left it for good long ago. Once he and his family flew to Pittsburgh for an event. Jennifer and their daughters took a day and drove the 27 miles south to Monongahela to see where Joe grew up. They plugged in the address and ended up at a collapsing house occupied by squatters. Joe stayed behind in Pittsburgh, like his grandmother, looking beyond whatever they might find in the old dirt.

WE GO TO lunch at a small Italian place near his office on the edge of North Beach and Chinatown. Joe orders the pesto for his pasta. It’s not on the menu, but they make it for him. He checks his watch. After lunch he’s got a meeting and then he promised to show a neighbor how to make an anchovy dip created 700 years ago two hours south of where Guiseppi Montani lived. Joe’s neighbor bought the ingredients and is paying for the lesson with a few Manhattans.

Sitting at the table, after we each order a glass of white wine, Joe tells me a story.

They were in Italy. Joe and Jennifer, their girls. His parents. Her parents. They got to Sicily, to the town where his mother’s family lived. They wandered into a little restaurant on a side street. The owner of the place played a trumpet whenever the mood struck. The grown-ups drank three bottles of wine.

The waiter came up to Alexandra. She was 18 months old.

“Vino, prego,” she said. The adults roared approval.

“I can’t give you wine,” the waiter said kindly.

“OK,” she replied. “Beer then.”

The room erupted. The staff loved this big American family. The Montanas ate and laughed. The owner played his horn. Later, the Montanas moved outside and found a nearby park where a man played accordion and local couples danced in the dust. The Montana girls joined in. Joe watched, smiling, holding on to the picture of it in his mind.

Back in San Francisco, our wine arrives. Big and crisp. Perfect for lunch. He raises a glass and says “Cheers.” We are at a table in the back with me facing the room. I can see the whispers and pointing begin. Depending on when you were born, Joe Montana is either the most famous man in the world or a fading former football star, but he is always Joe Montana. Well, almost always. There’s a funny story. A few years back he went to watch a family friend coach a college volleyball game at the University of San Francisco. The gym holds 3,000 people but when the game starts only about 200 are in the seats. Then Joe comes in. A half-hour later the stands are packed, the news of his appearance gone viral in the insular city. The crowd is now rocking, except the camera flashes are all middle-aged men trying to get a shot of Joe pumping his fist.

Before the third game the teams take a break.

One of the players is freaking out at the size and volume of the crowd.

“Where did all these people come from?” she asks in a panic.

Her coach apologizes and says it was his fault and he’d invited his very famous friend, Joe Montana. The girl grins and nods.

“Oh my god!” she says. “Hannah Montana’s dad is here?!”

Montana’s children say he likes being recognized more now than he did at the peak of his powers. He knows what it is like to be both canonized and forgotten. “I can see that heartbreak in my dad a little bit,” his daughter, Allie, tells me. “The more distance he gets from his career, the more time he spends reminiscing on stories.” But he’s learning to make peace with slipping from the white-hot center of the culture, too. His most recent Guinness commercial has him at a bar where he laughs when some young guy asks if he used to play pro tennis.

One of the recent California wildfires nearly burned down their big home in wine country. After they’d been evacuated a law enforcement friend called Joe and told him to come immediately if they wanted to save anything. The house held every piece of football memorabilia he owned. His home gym was full of it, floor to ceiling. They rushed in and had only minutes to get what mattered most. He and Jennifer grabbed family photographs and big stacks of the kids’ artwork over the years. They turned to go, but Nick stopped them as they headed out the front door. They’d left something priceless and irreplaceable behind, he said. He was right. They went back and carried out cases of Screaming Eagle cabernet and the old Bordeaux.

NOT FIVE MINUTES later we’re at the same table drinking the same crisp white wine from the same delicate stemware when the mood suddenly darkens. The trigger, I think, is a question about the bitterness of DiMaggio, who’d grown up so close to where we sat. Montana chafes at the word, bitter, and empathizes with the baseball legend.

“Some things stick with you,” he says.

A neuron fires in whatever part of his hippocampus that’s kept him as driven after four titles as he was before one.

“Are there things you’re still struggling to let go of?”

He pauses.

“I struggle to try to understand how the whole process took place with me leaving San Francisco,” he says. “I should have never had to leave.”

You wanted an audience with that other Joe Montana? Here he is. In the flesh, vulnerable and wounded, holding his hurt in his hands like a beating heart. Time seems to collapse for him a bit, as if an old wound is being felt fresh. We’re at the table waiting on pesto, but he’s somewhere else.

Jennifer Montana spots these approaching storms faster than anyone else in his life. Some mornings, she says, she sticks out her hand and says, “I’m sorry, my name is Jennifer. I don’t think we’ve met.”

A black mood can make him shut down.

“He’s so complex,” she says. “Joe, and you’ll hear me tell you this so many times, he has so many different personalities. There’s two or three main ones. The main one is about kindness. There’s a deep, deep kind of love and affection. And then there’s a moody, everybody-out-to-get-him kind of personality. It’s only true in his mind.”

He’s most sensitive when someone tries to take something from him. At every level he’s had to fight his way onto the field. Chuck Abramski wanted to replace him with a kid named Paul Timko. Dan Devine wanted to replace him with Rusty Lisch and Gary Forystek. Bill Walsh and George Seifert wanted to replace him with Steve Young. “It’s actually what was feeding the beast,” Jennifer tells me later. “He continually thinks of himself as the underdog and that they want to take this or that person wants this. They said I can’t.”

He sits at the table now reconstructing a timeline. Chapter and verse. In 1988 and 1989, he led the team to Super Bowl titles. His third and fourth. In 1990 San Francisco was leading the NFC Championship Game deep in the fourth quarter when he got hurt. Steve Young took over and Montana never started for the Niners again.

“Why wasn’t I allowed to compete for the job?” he says. “I just had one of the best years I’d ever had. I could understand if I wasn’t playing well. We had just won two Super Bowls and I had one of my best years and we were winning in the championship game when I got hurt. How do I not get an opportunity? That’s the hardest part.”

As Montana worked to recover, he says Seifert banned him from the facility when the team was in the locker room. Something ruptured inside Joe that still hasn’t healed. Those other coaches doubted him, fueled him, even manipulated him, but in the end they never pushed him out of the circle. A team was a sacred thing. Joe’s an only child — an essential detail to understand, former teammate Ronnie Lott says, because he lived so much of his early life in his own head — and his teammates became his family. All the old Niners knew Joe’s parents. They gathered around his mom’s table for ravioli. Jennifer made fried chicken for team flights. As much as Joe wanted to win football games he also wanted to belong to his teammates, and they to him.

“Why am I not allowed in the facility?” he says. “What did I do to not be allowed in the facility?”

Montana did his rehab alone. Isolated and wounded, he faced endless blocks of time. One way he filled it was going to a nearby airport for flying lessons. The 49ers facility was in line with the flight path in and out of the field. Every day he’d take off and from the air he could see his team playing without him.

“They wouldn’t even let me dress.”

He returned for the final regular-season game of 1992 and played well in the second half. On his last play Seifert wanted a run, according to Montana, who instead threw a touchdown pass. On the sideline, Montana says, Seifert threw his headset down. Word got back to Montana, who has never let that go, either.

He sighs.

He says he ran into Seifert the night before a funeral for one of the old Niners a few years ago. Jennifer and Joe walked into a hotel bar and there was George and his wife. Jennifer pulled Joe over to say hello.

“The most uncomfortable thing I’ve been through in a long time,” he says.

They tried to make small talk and then just fell silent.

“Inside I think he knows,” Montana says, before he moves back to talking about old Italian recipes and family vacations, the storm ebbing away. “You guys won another Super Bowl, but you probably would have two or three more if I’d stuck around.”

Three more, by the way, would give him seven.

WALMART ONCE PAID Joe Montana, John Elway, Dan Marino and Johnny Unitas to do an event. The four quarterbacks went out to dinner afterward. They laughed and told stories and drank expensive wine. Then the check came. The late, great Unitas loved to tell this story. Montana grinned and announced that whichever guy had the fewest rings would have to pay the bill. Joe had four, including one over Marino and one over Elway. Elway had two. Unitas said he only had one Super Bowl ring but had of course won three NFL titles before the Super Bowl existed.

Marino cursed and picked up the check.

Joe liked being king, is how his fiercest rival, Steve Young, puts it to me. I sit at a table in Palo Alto with Young, who laughs a little as he describes being around other guys who’ve dominated his position.

“You want to talk about a weird environment,” he says. “Go hang out with 10 Hall of Fame quarterbacks. Every one is kind of like … “

Young looks around from side to side at imaginary rivals. Preening stars and maladjusted grinders, insecure narcissists and little boys still trying to earn their father’s love, just a whole mess of somewhat unhinged alpha males with long records of accomplishment.

“… do we race?” he says.

IN THE PAST nine seasons, before retiring for the second time in as many years, Tom Brady won four Super Bowls. Montana watched those games, most at his home overlooking San Francisco Bay. He’s been known to sometimes yell at the television, not so quietly rooting for the Seahawks or Falcons. In an email to me once, Montana called him “the guy in Tampa” instead of using his name.

“He definitely cares,” Elizabeth Montana says. “I don’t think he would own up to caring, but he gets pretty animated at the Tom Brady comparison and is quick to point out the game has changed so much.”

Brady was 4 years old when he watched Joe throw the famous touchdown pass to Dwight Clark. He and his parents went together. Tom cried because they wouldn’t buy him a foam finger. That was 1982. Montana showed him the way. Both were underrated out of high school and both slipped in the draft because supposed genius coaches didn’t quite believe in them.

Montana watched Brady’s first professional snap in person. The Patriots played in the Hall of Fame preseason game in Canton just two days after Montana stood on stage there and delivered his induction speech. He’d awoken in the dark the night before to write it, finally figuring out a way to say what he felt.

“I feel like I’m in my grave in my coffin, alive,” he told the crowd. “And they’re putting, throwing dirt on me, and I can feel it, and I’m trying to get out.”

He was 44 years old.

They met for the first time not long after that. Montana invited him out to the house and they visited. Nate and Nick remember Brady serving as timekeeper as the brothers tried to see who could hold their breath longer in the swimming pool.

Brady won three Super Bowls in four seasons and then stalled. A decade passed. One night, working on a story, I drank wine and smoked cigars with Michael Jordan in his condo. We argued about sports and watched ESPN. A “SportsCenter” poll asked viewers to vote for either Montana or Brady as the greatest quarterback and this set Jordan off. At that moment Brady only had three titles and Montana had four, but the idea of the undefeated nature of time hit Jordan hard. “They’re gonna say Brady because they don’t remember Montana,” he said. “Isn’t that amazing?”

Brady missed an entire season to an injury and lost two Super Bowls. He looked at his hero’s career and saw the warning signs coming true. Once at an event in Boston he got interviewed by positive thought guru Tony Robbins and talked about how he saw injuries derail the career of Montana. His almost religious dedication to prolonging his career was in some part born out of Montana’s pain. In 2015, seven months before Montana founded Liquid 2, Brady won his fourth Super Bowl.

When Pete Carroll called for the pass that ended up in Malcolm Butler’s hands, Montana yelled what everyone else did, but with a little more on the line.

“Give the damn ball to Marshawn,” he says.

In 2016, at Super Bowl 50, the game’s greats all returned for a ceremony. It was a big enough deal that Jennifer Montana went into the safe and took out all four of Joe’s rings to wear on a safety pin as a brooch. Nearly every living Super Bowl MVP took the field. Montana was cheered. Brady, recently shadowed by deflated footballs, was booed. A month later Brady and Julian Edelman worked out in Brady’s home gym. “Houston” was written on a whiteboard. Edelman asked what it meant, and Brady said that’s where the Super Bowl was being held that season.

“We’re gonna get you past Joe,” Edelman told him.

Brady stared at him.

“I’m not going for Montana,” he said. “I’m going for Jordan.”

Brady liked to text Joe from time to time and talk about breaking his record. Joe laughed but his inner circle quietly bristled. I ask Steve Young if Tom Brady knows he’s in Joe Montana’s head? “I think anybody that traffics in this space knows exactly what’s going on,” Young says finally. “But everyone has to recognize and appreciate that’s how you get there. Joe is not immune.”

Montana’s family is protective of his legacy. His sons accurately point out that no modern quarterback has ever taken hits like the ones their dad absorbed regularly. Jennifer correctly says the game has changed too much to compare eras and that he played in four and won four. But four is still less than still seven. Recently Brady and Montana were voted by the NFL as two of the greatest quarterbacks of all time. “I’m sure there’s a kid out there somewhere who’s looking at this list, watching tape of me and Joe and making plans to knock both of us down a spot,” Brady said.

Brady praises Montana as “a killer” in public, but Joe’s friends feel like he’s made little effort to get to know the older player in real life. They have each other’s phone numbers. Something about Brady specifically seems to irritate Montana — friends say he’d be happy if Patrick Mahomes won eight titles — but the truth is, the two men are similar, driven by similar emotions to be great. Ultimately Montana may not care about a ring count, but watching himself get knocked down a spot fires deep powerful impulses and trips old wires even now.

IN THE PAST several years Montana authorized and participated in a six-part docuseries, which came as a shock to people who knew how militantly the quarterback guarded his privacy. The documentary, “Cool Under Pressure,” premiered in January 2022, just two months after Brady’s own docuseries. The opening narration sets the frame Montana sees for himself: “For decades he was considered the GOAT of quarterbacks. What most don’t know is he spent his whole career being doubted.”

The Montanas watched the first rough cut of the documentary on vacation with their closest couple friends, Lori Puccinelli-Stern and her husband, Peter Stern. Joe puttered around the kitchen because he doesn’t like to watch himself, listening from afar. Jennifer sat on the couch and got so nervous she started braiding Lori’s hair. Every now and then Lori would hear her quietly say, “Oh my god, he never told me that.”

For decades she had heard Joe’s parents talk about how he’d had to fight through coaches in high school and college. Sitting there watching the film, she realized they hadn’t been exaggerating. It shocked the kids, too. They see him as such a conquering hero, preordained, even, that the obstacles placed in his way surprised them. Joe’s youngest son started making mental notes about questions he needed to ask about college and his experience with Walsh.

“I never knew how s—-y he got treated at Notre Dame,” Nick Montana says. “I never knew how s—-y he got treated at the Niners. My first question was: Why do you still like Bill? He talks about him like he’s a god. How are you still cool with that guy?”

Peter, a tough former Berkeley water polo player, looked visibly shaken at the physical punishment Joe absorbed. There’s Joe in the back of an ambulance and Joe crawling around on the ground like a war movie casualty and Joe loaded onto stretchers and carts.

The violent league he dominated no longer exists. He got knocked out of three different playoff games with hits that would now be illegal. Jim Burt hit him in 1987, and the camera settles on Montana seeming to mumble. He was knocked cold and taken away in the back of an ambulance. In the fourth quarter of the 1990 NFC Championship Game, he rolled out, dodged Lawrence Taylor and looked downfield. Leonard Marshall hit him from behind, helmet to helmet, driving Montana’s head down into the turf. The hit broke his hand, cracked his ribs, bruised his sternum and stomach and gave him a concussion. Steve Young sprinted onto the field in concern and got to Joe first.

“Are you all right, Joe?” he yelled.

“I’ll be all right,” Joe whispered.

The team doctors asked where he hurt.

“Everywhere,” he told them.

Montana, who looked like a golden boy with his hair and his Ferrari, knew the secret to winning football better than anyone. It wasn’t athleticism or mental acuity or even accuracy.

“Suffering,” Ronnie Lott says.

LOTT LEANS IN across a table in a Silicon Valley hotel lobby, missing finger and all. His eyes dance with aggression and wonder and his voice sometimes drops to a menacing whisper. His friend Joe, back when they were young, loved the suffering, he remembers, because in it lay redemption and victory. Catholicism and football are so alike, it’s no wonder so many great quarterbacks rose from industrial immigrant towns perched above rich coal deposits deep in the Pennsylvania ground. But the geographical trope often overshadows how personal a quest must be to survive a climb to the mountaintop.

“It was his commitment to going to the edge,” Lott says, “and part of that going to the edge is: Are you willing to go there because you feel like you can go beyond that? The reason I think Joe has taken that position in his life is that his dad took that position. He taught his son, “Hey, look, you have to be willing to go die for it.'”

Lott knew Joe’s parents and is Nick Montana’s godfather, a role he takes as seriously as you might expect from a warrior monk. He knows Joe inherited his values and impulses from his dad but any deeper understanding remains out of reach. Montana is as much a messy tangle of pride, longing and striving as you or me or Ronnie Lott. That’s part of Montana’s inheritance, too. His teammates looked at him and through the glass darkly saw the best version of themselves. That’s a quarterback.

Lott’s voice cracks.

“I’m always amazed at some of the things that we don’t know about his love, his perfection, about his will,” he says. “If I knew I was going to die, I’d probably want to sit there and just stare at him. Because he’s going to instill something in me that’s going to say, ‘You’ve still got another one. You’ve still got another one. You’ve still got another one.'”

Ronnie wants to tell me a story that might show what he’s struggling to say. Once in the locker room Bill Walsh singled out and berated Bubba Paris for being fat. Then the coach wheeled around to the locker room for a final bit of theatrical punctuation.

“Anyone got anything to say?” Walsh barked.

The whole team stayed quiet. Ronnie. Jerry. Roger. Everyone.

Joe stepped forward. Nobody messed with his team.

“I’m taking care of his fines.”

The room fell silent.

“If anybody’s got anything to say about it … ” he continued, and nobody said a word — not even Walsh.

Ronnie is telling this story because something like it happened daily. The often opaque Montana’s native tongue is example. He almost got hypothermia during a college game once but still returned to win the game. His body temperature was 96 degrees. Sitting in the Notre Dame locker room, he calmly drank chicken noodle soup until it rose enough for the doctors to let him back in the game. “How many weeks did I see him on Wednesday and say there’s no way,” Young says. “There are tons of times in games when I thought there was no physical way he could play, and he would play and play well.”

In the 1993 AFC title game, Bruce Smith and two teammates drove Montana’s head into the ground. Smith heard the quarterback moaning and got concerned. He asked Montana if he was OK but Joe couldn’t understand the words.

“The one in Buffalo was a felony,” close friend and former teammate Steve Bono says.

The hit ended the Chiefs’ playoff run and hurried the end of Montana’s career.

“He was pretty sure after that Buffalo concussion,” Jennifer said.

She told him to take his time and to be sure of his decision.

“Do you want me to play?” he asked.

“What I don’t want you to do is say, ‘I retired’ and then take it back,” she told him.

He played one more season.

He hurts a lot at night now. Sometimes he gets out of bed and sleeps on the floor. After one back surgery his doctors made him sleep in a brace. He hated it. Jennifer would wake up and catch Joe trying to quietly undo the Velcro one microfiber at a time. She knows how to stretch his legs to bring relief and can tell his pain level just by looking at him from across a room.

Montana accepts that pain is the price football extracts. It’s easy to imagine why the success of Tom Brady, who got out without any scars, would seem like a violation of the most basic codes of the game. Growing up, Montana idolized Johnny Unitas, who made the plays and took the shots. Joe wore No. 19 as a kid. A photo exists of him as a rookie wearing a Niners No. 19, but when camp broke, the equipment managers assigned him No. 16 instead. The next time Montana chose a number again, with the Kansas City Chiefs, he picked No. 19. Years later Joe and John played golf together in North Carolina. On the first tee, Montana confessed that he’d just purchased a Baltimore Colts No. 19 jersey, the only piece of sports memorabilia he’d ever bought.

“You should have called me,” Unitas told him. “I’d have given you one.”

Football had destroyed Unitas’ body and he needed to Velcro his golf club to his hand in order to swing. “Johnny was so bitter against the NFL,” Montana remembers, but he also remembers it as a great day, because bitterness and pain seemed like a price both men agreed to pay when they first stepped under center and asked for the ball.

Since his last game Montana has endured more than two dozen surgeries. Maybe the worst was a neck fusion. He stayed in the hospital for about a week, and as he checked out, Jennifer called Lori and Peter and asked them to come meet them at the house. Joe wanted to play dominos. (Joe and Lori play an ongoing game against Jennifer and Peter.) Lori walked in and turned away. Joe looked terrible, thin, wearing a neck brace. He ate a little salad and faded in and out. Lori walked outside and cried. It’s like she realized for the first time that even Joe Montana was going to age and die. She turned around to see that Jennifer had followed her. They two women hugged and then Jennifer gestured upstairs.

“If you asked him right now if he would do it again,” she said, “he would answer in one second. Absolutely yes.”

STEVE YOUNG IS sitting in his Palo Alto office and thinking about why Montana would do it all over again, and why he would, too. There’s football memorabilia everywhere on the walls and shelves. The market closes in less than five minutes. As financial news scrolls across a huge screen, he searches for the right way to describe how he feels now about Joe Montana.

“I don’t want it to be a weird word,” he says.

He’s got an idea in mind but is nervous.

“Tenderness,” he says finally.

Time has revealed so much to Young, who is probably the most thoughtful member of the Hall of Fame. Namely, that time itself is both the quarterback’s greatest enemy and most precious resource. The shiny monument and the inevitable swallowing sand. That knowledge rearranges the past. All those years ago he just wanted snaps with the first team, to be QB1 and take his place atop the food chain. Now he understands. He wasn’t trying to take Joe Montana’s job. He was trying to kill him, to take away the air in his lungs and the ground beneath his feet, to burn down his home and bury the ashes. He took years away and left blank pages where more Montana legend might have been inscribed. Fans and pundits measure a career in terms of titles and yards and touchdowns. Players get seduced by those, too. But in the end those metrics are merely byproducts of a complicated and deeply personal calculus, each man driven by different inheritances and towards different birthrights. There isn’t a number that feels like enough. The goal is always more.

“Every player in history wants to write more in the book,” Young says. “I think about that all the time.”

His voice gets softer.

“No matter how much you write,” he says, “you want to write more.”

Young goes quiet.

Then says, “I’ve talked to you more about this than he and I would ever consider talking about it.”

Bill Walsh traded for Young in 1987 because he worried Montana’s back injury might end his career. Joe actually thought about retiring then but the competition with Young filled him with determination. When Steve stepped onto the field for his first practice, Montana looked him up and down and said, “Nice shoes.” They had No. 16 written on them. The San Francisco trainers had put a pair of Joe’s cleats in Steve’s locker. The fight was on. Montana held off the younger, more athletic Young until his injury in 1991. If you read Young’s autobiography, it’s actually a book about Joe Montana.

“I guess in some ways I admire him in a way that no one else can,” Young says.

He says he gets it. Montana retired at 38. Brady won three Super Bowls after turning 38. The violence that drove both Steve and Joe into retirement was erased from the quarterback position Tom dominated for 23 seasons.

Montana can only sit and watch.

“I think he thought what he wrote in the book was plenty,” Young says, “and I think he’s a little surprised it didn’t turn out that way. That’s why it probably bugs him. If he could … he wouldn’t allow it. With our age, we’re stuck. We’re in the same boat. I definitely have spent time wanting to write more in the book.”

I say something about Brady calling Montana a killer.

“A predator has no feeling,” Young says, suddenly defensive of his former rival. “Joe was a good dude. Assassin doesn’t work. He’s more emotionally athletic than that. An assassin is not emotionally athletic. A predator is not emotionally athletic. You’d be doing him a disservice. You don’t get there without being a spiritual, emotional and physical athlete. But that dynamic doesn’t rule the day. It’s not like that’s all you are.”

To Young former quarterbacks are virtuoso violinists who have their instrument stripped away just as they master it. He wants another stage. Unitas did, too, and Montana, and Elway, and Marino. One day, so will Brady.

“Everything would be informed by that desire,” Young says. “Please give me the violin back. Please … “

He smiles. Thinks.

“The day you retire you fall of a cliff,” he says. “You land in a big pile of nothing. It’s a wreck. But it’s more of a wreck for people who have the biggest book.”

His wife has been texting but he got lost in his memories about Joe. Young asks me to tell Montana hello for him and then packs up his stuff to go on the afternoon school run. I turn and look around his office. A framed No. 16 jersey hangs on his conference room wall.

JENNIFER MONTANA MEETS me in a little breakfast place she likes by the water. She comes into the room with pink Gucci slippers and a wide, friendly smile. It’s early in the morning. Her art studio is around the corner, and she does a lot of sculpture and painting. Yesterday she and Joe drove around the city with the windows down. They got to a stoplight and the person a lane over hurriedly rolled his window down, too. He had a few seconds’ audience with Joe Montana.

“Thank you for the great childhood,” the man said.

We find a corner to talk.

“I think he really fought in the 15 years after retirement,” she says.

They met on the set of a razor commercial. He’d been divorced twice. She was the actress tasked with admiring the matinee idol quarterback’s close shave. He wanted to ask her out and fumbled hard on the approach, which she found endearing. They’ve been married nearly 40 years now and are very different. She is lit from the inside with the beatific now. He still has the aspirational immigrant struggle between discovering and remembering imprinted on every cell.

“I think the talks that we’ve had is … everything is right here,” she says. “You have the world at your feet and you have to remind him of that on occasion, because the thing that motivates him is not having the world at his feet.”

He became a good pilot. For a few years he competed in serious cutting horse events. Neither of those made him feel valuable again. A business he owned with Ronnie Lott and fellow teammate Harris Barton failed. He’d been retired for 20 years, a long gap between successes, before he got into the venture capital world and rediscovered any kind of a familiar rush. That’s a lot of wandering. “You’ve got a family that loves you,” she says. “You’ve got four healthy, beautiful children. We’re in love. You’ve got money in the bank. What could you really want for? But it didn’t solve the problem of looking for the next thing.”

They experience time differently. She urges him to look at the rising sun and be happy. He loves that view but remains tethered to his own suspicion of happiness, his own belief in the value of suffering. Bridging that tension has been their shared task.

He loved being a dad after football — although other parents in Napa Valley gossiped about how the intense rust belt sports dad didn’t vibe with wine country chill — and worried a lot about everything he’d missed while winning four Super Bowls. Like a lot of children from his neck of the woods, raised on the dueling icons of the crucifix and the smokestack, he’s a complex mix of work ethic and guilt. He wants a big family. He also wants to work hard, to achieve as only an individual can. These days if he’s in an honest mood, he’ll describe the deep regret he feels about how much football took him away from his kids. Never mind that Jennifer says his guilt is mostly internal and not rooted in the reality of their lives. He was there, she insists. Sometimes he got too involved when the season ended, stepping back into her world and messing with the system. “To this day it makes him melancholy to think of how much he missed,” she says. “And I go, ‘Joe, you really didn’t.'”

The four Montana children have a complex relationship with their father’s fame. His daughters heard all the mean comments kids made, supercharged by jealousy. They were embarrassed at all the attention. About the only two boys in America who didn’t want to wear Montana on their backs were Nate and Nick, whose jerseys had their mother’s maiden name on them during youth football, trying to find even a sliver of daylight between their father’s accomplishments and their own. In hindsight they’ve come to believe he intentionally dulled his own legend for their benefit. “I think something that over time I appreciate more and more is how much effort he put into family,” Nick Montana says. “There’s obviously a lot of things he could have done post-career to garner more fame, more wealth, but the most important thing to him was being present for us.”

That sentiment makes Jennifer smile. She knows it’s true and went against her husband’s natural wiring to compete and win. This winter we meet up again at a trendy breakfast spot down in Cow Hollow. She drives the few blocks from their house on her white Vespa. We talk a lot about how he is happy but still has work to do on himself.

“I want him to be content,” she says.

Most of the time, he is. Most of the time. Every now and then he’ll experience what can best be described as a biological response. He built himself to respond to challenges both real and imagined. Jennifer will be sitting next to him in a car and he’ll start gunning the engine, moving in out of traffic, and she’ll have to remind him that some other driver isn’t trying to race, or to cut him off, or to start some competition on the freeway.

In those moments, she says, “He still hasn’t figured it out.”

Sometimes Jennifer worries he feels the best part of his life is over and her main role now is to counter that with reminders and activities. His flaws — the guilt, the pettiness, the occasional dark cloud of blame and paranoia — are part of why she loves him. He will always be a guy who sees the glass as half-empty. That’s what allowed him to become and to be Joe Montana. Sometimes she gets tired having to throw boundless positive energy at one of his black moods. But in the end, the complications are the man, not some wilderness to hack through while looking for him. The untamed part of him is why she’s still here all these years later. “I think we’re each other’s best friend,” she says, “and it’s not always pretty, but it’s pretty darn good.”

FIVE YEARS AGO his father died. They’d been so close. Joe Sr. used to show up at Notre Dame unannounced in the middle of the night, after a six-hour drive, just to take his son and his roommates out to a diner. In 1986, Joe’s parents moved full time to California. His mom died in 2004. The family buried Joe Sr. in the rich wine country dirt. Next to Joe’s mom. The San Francisco Bay was the home this family had been searching for since Guiseppi Montani set sail in 1887. Four people gave Joe’s dad eulogies: his four grandkids. Allie started to break down and Nate moved to the front of the church and stood by her side.

They’d entered the stage of life where people started to fall away. A year after his father died, his best friend, Dwight Clark, died, too, after a battle with ALS. They met as rookies, bonding over beers and burgers at the Canyon Inn by their practice facility. They became legends together, navigating a bitter falling out and ultimate reunion. In the end they kept faith with one another, knowing or maybe learning over the years that what they accomplished meant less to them than the fact that they’d done it together. As Clark slipped away, Montana sat by his bedside. The old Niners worked out a schedule to be sure Dwight was never alone.

When he got the news Joe fell apart. Jennifer called Lori and asked if she could talk Joe down. Sometimes she can get through to him when nobody else can. “I talked to him on the phone for 45 minutes,” Lori said, “and he was sobbing so hard he couldn’t breathe.”

Before he died Dwight had asked Joe to deliver a eulogy. His first draft skimmed along the surface — there was a limit, he felt, to how deep he could go without just dissolving in public — but Jennifer told him he needed to rip it up and start again. This wasn’t a sports speech. Joe’s second draft hit the mark. He was poignant and funny. He said Dwight loved to remind him that, you know, nobody called it “The Throw.” Everyone laughed. His voice cracked. Jennifer sat in the audience next to their old friend Huey Lewis. Back in the day, Joe, Dwight and Ronnie sang backing vocals for Lewis’ hit song “Hip To Be Square”; that’s them crooning, “Here, there, everywhere.”

Huey leaned over and told Jennifer he felt sorry that Joe was always the guy who got asked to speak at funerals. After all these years he remains their QB1. Just a few months later, as part of the new stadium in the southern suburbs, the Niners dedicated a new statue to “The Catch.” There’s Montana with his arms raised in the air. Twenty-three yards away Dwight Clark is frozen in the air with his fingers on the ball. The team asked Joe to speak on behalf of himself and Clark.

“I miss him,” Joe said.

Montana spoke with humility — calling out Eric Wright, whose tackle after “The Catch” actually won the game — and talked about how time and age were ravaging their once strong team. Opponents once lost sleep thinking about the San Francisco 49ers coming into their city and now they were old enough to be dying. They were in that strange transition from people to memories.

“It’s truly an honor … ” he said.

Montana looked at the statues of himself and his best friend.

“… to be remembered forever.”

His friends felt he was more emotional that day than at the funeral. It was a little chilly with clear skies. Joe looked down to his left and saw Dwight’s children. “He was looking in the eyes of mortality,” Lori says.

THE PANDEMIC BROUGHT everyone home.

For the first time since Allie went to Notre Dame in 2004, minus a couple of summers, all six Montanas were together all the time. What a gift! Empty nesters never get their birds back. And there weren’t just six of them anymore. The first grandbaby had been born and another was soon to follow. Everyone worked from home, and three or four nights a week gathered around a big, loud table at Joe and Jennifer’s place. Nate usually handled the music unless they watched a game or movie. Joe and Jennifer loved it. They laughed and ate and danced and gave thanks for their growing family. They hung out in the backyard. Joe has every grill imaginable out there, with Jennifer always finding bigger and better ones to work into the mix, so they watched him cook and made cocktails.

Joe asked me once if I knew the quiet sound of a gondola cutting like a blade through the shadow-thrown canals at night. He loves a moment, whether it’s cataloging the way ice hits a glass in a Basque beach town or looking over at the sideline and noticing John Candy watching the game. Because he trusts and loves Jennifer, he’s trying to learn to better manage the blank spaces between moments, but he does have his own version of contentment. He’s a romantic at heart, equally at home in dive bars and triple-deck yachts. They’ve traveled constantly, with their family, and with friends. Boat trips to the south of France and rain forests in Costa Rica, again and again, and long winding journeys up and down Italy. The whole family met up this last summer in Istanbul where a fan stopped him for a picture in the streets. He shopped in the ancient stalls in the old town souk. They sat at a café where boats nosed up right to the dock. His travel tips for the beaches of Europe belong in a book. They’ve bungee jumped in New Zealand and ran with Bill Murray at Pebble Beach. Five years ago he did the full five-day climb up Machu Picchu with Jennifer and the kids. Everyone was worried about him, but he tapped into something inside and endured the pain. One foot in front of the other. For a bit the boys had to carry their backpacks, but mostly Jennifer just kept barking at anyone slowing down and Joe marched in determined silence. They made it up and he looked out through the beams of light. He’d earned this moment. At his feet the emerald green grass grew through the stone ruins and around him dark peaks rose in the air like cathedrals.

Once the pandemic travel restrictions loosened the whole family went to the North Shore of Oahu. It’s a surfing paradise. They’d booked two weeks. Two weeks turned into a month. They kept traveling together, chasing sunlight and water, Costa Rica, back to Hawaii, down to the islands, then to their little weekend place in Malibu. They surfed, they fished, they played dominos, they ate fresh seafood as the sun sank into the water.

They moved as a pack and that’s how I found them when I arrived in San Francisco last summer to meet Montana for the first time. He seemed like a case study in a psychology journal: forced to leave a job he did better than anyone who’d ever come before, forced to try to find a replacement for the time and passion that job required, forced to undertake that search while a kid who grew up idolizing him tore down his record and took his crown. If you wanted to understand the fragility of glory and legacy, Joe Montana isn’t a person you should talk to about it. He is the person.

“Look at Otto Graham or Sammy Baugh,” Joe says as we sit in his office during our first meeting, seeing his place in a continuum that existed before he entered it and will exist once he’s gone. He knows intellectually that comparison is a foolish talk radio game and yet. A bit later, unbidden, he says he wishes every living human could have the experience of standing on an NFL football field on a Sunday afternoon. Just to feel the way crowd noise can be felt in your body, the sound itself a physical thing, waves and vibrations rolling down the bleachers — 80,000 voices united coursing right through you. Mickey Mantle sat in the rain in his car looking for that noise. Joe DiMaggio stared out at the San Francisco Bay hoping to hear it come through the fog. Even talking about it gives Montana chills. If the number of titles separates the men on the quarterbacking pyramid, then the memory of the game, the feel of it, connects them. That’s Joe’s point about Otto and Sammy. “Those guys were so far ahead of the game,” he says. “I don’t know how you compare them to today’s game or even when we played.”

It’s the moment that matters. Not records. He was fine to let his trophies burn. He misses the moments. The moments are what he thinks about when he sits at home and watches Brady play in a Super Bowl. He’s not jealous of the result or even the ring. He’s jealous of the experience.

“To sit in rare air …” Ronnie Lott says, searching for the words.

“… is like being on a spaceship.”

Breathing rare air changes you. Every child who’s sucked helium from a birthday balloon knows this and so does Joe Montana and everyone who ever played with him. It’s the feeling so many kids hoped to feel when they slipped on the No. 16 jersey and let the mesh drape over their arms.

“He breathed rare air with me,” Lott says, and the way he talks about air sure sounds like he’s talking about love.

TOM BRADY RECORDED a video alone on a beach and again told the world that he was done with football. For good this time, he said with a tired smile. His voice cracked and he seemed spent. He’s a 45-year-old middle-aged man who shares custody of three children with two ex-partners. Next year he’ll be the lead color commentator for Fox Sports. This past year he’d just as soon forget. He retired for 40 days, then unretired and went back to his team, looking a step slow for the first time in his career, and finally retired again. Those decisions set off a series of events that cost him the very kind of family, the very wellspring of moments, that have brought Joe Montana such joy. Brady has fallen off the cliff that Steve Young described and faces the approaching 15 years that Jennifer Montana remembered as so hard. Tom’s book is now written. He will leave, as Montana did before him, the unquestioned greatest of all time.

“You cannot spend the rest of your life trying to find it again,” Young says.

Stretched out before Brady is his road to contentment. The man in the video has a long way to go. Montana knows about that journey. He understands things about Brady’s future that Tom cannot possibly yet know. On the day Brady quit, Montana’s calendar was stacked with investor meetings for the two new funds he’s raising. When he heard the news, he wondered to himself if this announcement was for real. Brady had traded so much for just one more try. On the field he struggled to find his old magic. His cheeks looked sunken. His pliability and the league’s protection of the quarterback had added a decade to his career. But along the way they also let his imagination run unchecked. Brady’s body didn’t push him to the sidelines. He had to decide for himself at great personal cost. Montana was never forced to make that choice. He had to reckon with the maddening edges of his physical limits but was protected from his own need to compete and from the damage that impulse might do. For all his injuries took from him, they gave him something, too.

THEY’VE GOT TWO grandchildren now, Lil Boo and Bella Boo, and a third on the way.

“A boy,” Lori says with a grin.

The momentum of the pandemic hasn’t stopped. Jennifer has planned a monthlong trip to the coast where Spain and France meet. Everyone is coming. All four kids and the grandbabies. Joe and Jennifer are flying to Paris three days early. Just the two of them, so they can walk alone through the Tuileries Garden, holding hands in the last warm kiss of fall. She’s checked the rotating exhibits at the Modern but there’s nothing that she’s dying to see, so mostly they’ll just sleep and walk the city and spend meals talking about what they’ll eat next.

“Baguettes in the morning,” she says. “Coffee to lunch to dinner.”

When Joe and Jennifer take stock, they’re pleased. Sure the boys’ college football careers didn’t end how they wanted, and Joe is still upset the Niners wouldn’t sign Nate and give him a chance in the pros, but all four kids have graduated from college. Both girls went to Notre Dame like their dad. Both boys work in venture capital and each has created success on their own. Joe didn’t hire Nate until he went out and built and sold a company of his own. They have good manners. The boys — men — stand up and shake hands when a stranger comes to their table. Nick, the youngest, just turned 30. When I visited, all four kids were living in the city. Jennifer, who does not pull punches when talking about her complex man, says Joe is happier than he’s ever been.

One Sunday when I was in town they had a big family barbecue. The FAM2 text chain came alive with plans and details and instructions. (FAM1 was retired because Nate’s girlfriend got added, which required a new group.) They gathered on their big rooftop terrace with views of both bridges. Joe made ribs. Everybody hung out for hours. None of the kids were in a hurry to leave. The two little girls ran around shot from a cannon, demanding attention. His grandchildren are the path to the ultimate contentment Jennifer wants for him. Everyone who knows him says so.

Allie went into labor late at night and she remembers the first time she saw her dad hold the little baby — “love, wonder, excitement — literally like a kid who just got the baseball card they had been buying all that gum for …” — but also what she described as “profound sadness and longing.” Even as he held his family’s future in his arms he thought of his mom and dad not getting to meet this baby and, Allie thinks, not getting to see their son be a grandfather.

The grandkids call him Yogi. Jennifer is Boo Boo. He loves it when they teeter down the hall and crawl into bed between them. A few days ago Lil Boo spent four straight nights with them. She is taking swim lessons at a club in their neighborhood. Joe gets her dressed in a cute pink bathing suit and takes her down to the pool. All the other kids have their moms, so that’s the scene. A bunch of screaming kids, with their San Francisco mothers in the pool — plus one former quarterback splashing and smiling.

“It’s so interesting to see him with these grandbabies now,” Lori says. “He missed all that when his kids were young. He’s like a little kid himself. After all the ups and downs, all the surgeries, all the moves, the kids — you’re only as happy as your most miserable child — right now to me it feels like all the kids are settled, they’re all kicking ass. But the biggest change in our 30 years of friendship is them being grandparents — there’s even a new connection between them. When Lil Boo does something hysterical, they’ll look at each other with this … this is the result of us.”

On a recent trip to Costa Rica, Joe and Jennifer took Boo out into the surf and gently and carefully got her on a board. Jennifer rode with her while Joe stood behind them, holding tight to the cord, watching with pride. Not long ago Lil Boo announced she wanted to ride on a cable car. This would be Joe’s second time on one of them (his first was filming a United Way commercial years ago while Tony Bennett stood next to him and crooned, “I left my heart … “)

Joe and Jennifer led the little girl outside and toward the closest trolley. The conductor was rushing past them, certainly not going to stop, until he saw who was standing there trying to flag him down. He hit the brakes. These are the great joys of being Joe Montana now.

He can make a cable car stop for Lil Boo.

NOT VERY LONG ago Joe wakes up early before work and in the particular quiet of a morning house, he mixes the water and the flour and gets pizza dough made and resting before he heads into the office. Nate and Matt are waiting on him downtown, between the Transamerica building and the trattorias and pool halls of Joe DiMaggio’s youth. They have a busy day listening to pitches from founders ahead. It’s warm in San Francisco, high 60s and rising, with no marine layer tucking the city into a pocket of grayed white.

They’re launching a new fund, designed to push more capital to companies they’ve already decided to support. Joe is raising the money and he says when that’s done he might finally step back from the daily grind. Jennifer doesn’t believe that for a moment. A big Post-it note in his office lists the ways in which they’re planning to grow, to make the business larger and more complex. That’s why Matt is here, to help with the investments but also with the structures and processes of a larger firm.

“We’re always going to be innovating,” he says.

We’re sitting around a conference table. Someone’s left two Tootsie Rolls on a Buddhist shrine as a kind of offering. Nate is eating noodles. Joe is talking about how football kept him from studying architecture and design at Notre Dame because those classes met on fall afternoons. He scratches his ear and hunches over the screen. Jennifer told me to correct him when he used bad posture which I obviously do not do.

When the presentations end for the day Joe heads home. FAM2 is a flurry of activity. Tonight is pizza night for the Montana family of San Francisco, California, and it’s hard not to think about Guiseppi Montani and whatever his wildest dreams for his descendants might have been when his ship pulled out of the harbor. Later that evening an email arrives on my phone with six pictures attached. I open them. Joe Montana has sent over photographs of his pizzas. There’s good mozzarella and fresh basil on one. Thick wedges of pepperoni and mushrooms on another. The crusts look charred and chewy. The next morning he grins and says they turned out pretty well but he still has room to improve.