I had played at Wrigley Field many times, mostly as a homegrown Chicago Cubs player but also as a Philadelphia Phillie. In 2003, though, I returned to Chicago as a hired hand, dealt on July 30 by the Texas Rangers for cash and a minor league catcher — right before the MLB trade deadline.

And I wasn’t exactly thrilled about it.

When I was told I was traded, it was by phone. When I went to say my goodbyes in the Texas clubhouse the next day, my locker was already packed. I was gone before I was gone. That was hard. I would miss manager Buck Showalter’s humor. I would miss teammates like Michael Young, Juan Gonzalez and Alex Rodriguez. I would miss our wild team meetings. I would miss my fan club program — the Good Grades Club, where students would mail me their report cards for an autographed photo or other rewards, a brilliant idea by the Rangers’ marketing team. Now the mail would stop.

Worst of all, I was 32 years old, recovering from a torn hamstring tendon, and after hobbling around minor league rehab for a month, I had finally got my timing together. No one could get me out in the American League in July: I posted a .925 OPS that month, and despite a dismal season for Texas (we were in last place when I was traded), I was building my way back to being a viable free-agent candidate and a starter again. I didn’t want that run to end on someone else’s terms. But it did.

This week, many players will have these kinds of feelings and more. Lost, revitalized, the new kid, the old vet, pushed out of a job, last to first, starter to bench guy, all in a simple transaction — with no guarantees as to how the story will end.

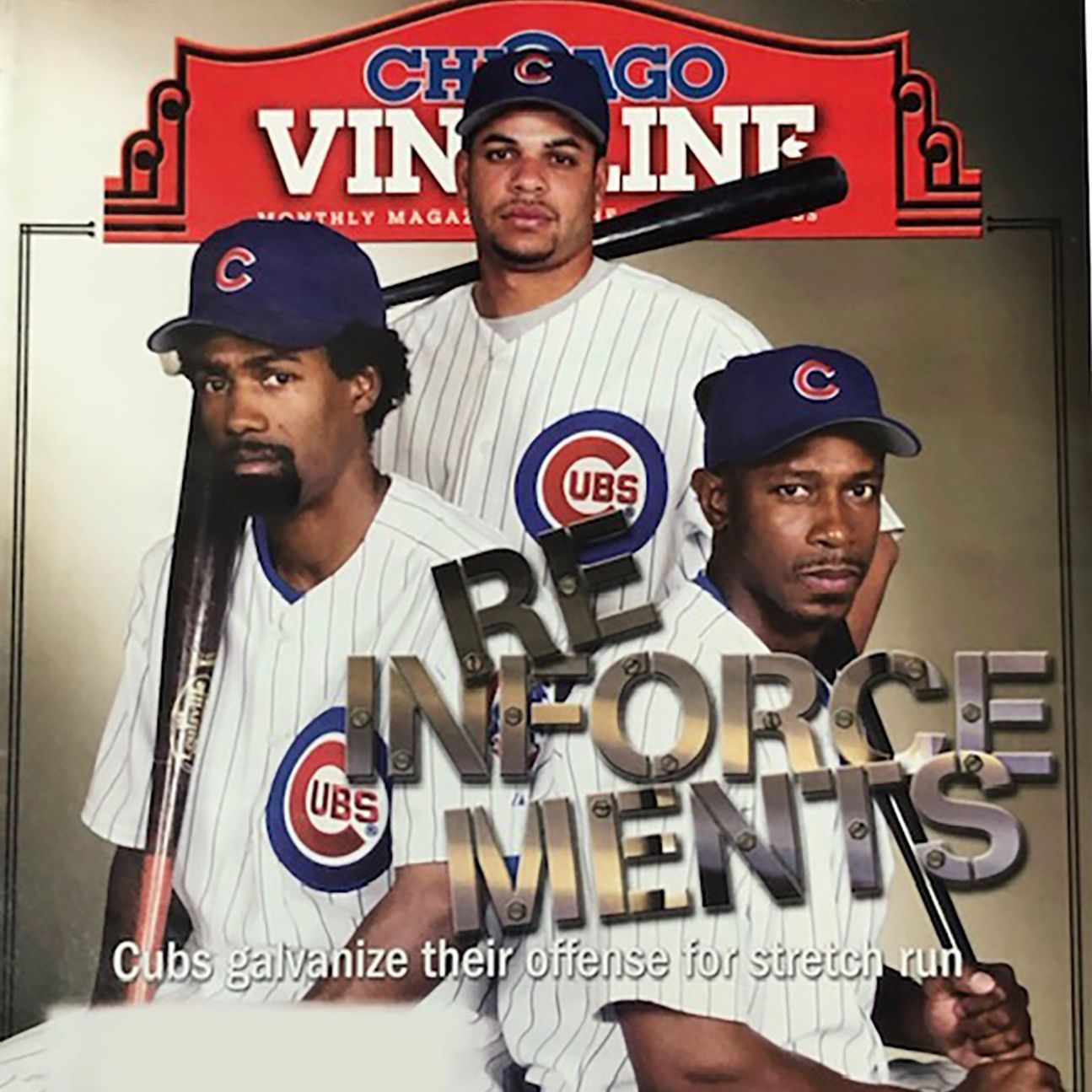

One of the first things I did after returning to Chicago was a photo shoot with other traded-for Cubs. Kenny Lofton and Aramis Ramirez joined me for the cover of the Cubs’ monthly Vine Line Magazine. That picture is worth a thousand words, my feelings of disillusionment on full display. I had not cut my hair since the year before, and I kept thinking about how I was traded from where I was playing every day to where I would be a platoon player at best. Sure, the postseason is the goal — especially after a career, at that point, of champagne-less offseasons — but I also needed to have a job to even think about October. Getting 50 at-bats in two months might not be enough to make a roster.

At least they seemed glad to have me. On my first day as a new Cub, manager Dusty Baker greeted me and expressed his excitement with my joining the team. The man matched the legend, barrel-chested and imposing, yet looked you in the eye with a certain warmth and understanding. I immediately learned about the chewing sticks and the green tea he kept close by in the dugout, the health drink he relied on as he recovered from prostate cancer. He did not promise me a starting role, but he knew what I could do — after all, I had played against his Giants plenty of times.

I had only heard, secondhand, about Baker being this amazing players’ manager, but I had a wall of emotional iron around me, and it was hard for me to take it in. He didn’t know of my long journey in the Cubs’ minor leagues to get to Chicago. My war with my Triple-A manager, my watching outfielders lap me to reach the big leagues or how I lost my father on the last day of the 2002 season. Even though I had been long gone from Chicago by the time this trade went down, I had the baggage of being traded before. That hard lesson about not having control of my future, the feeling of being property even if the other side thought they were getting a gift.

I learned that Lofton was our center fielder and I would play against some lefties and come in to pinch hit or pinch run, maybe play some defense late in the game. After starting for my entire career, it was an ego check, and because I never felt I got a shot to be that starting center fielder in Chicago, it felt worse. First, the Cubs didn’t bet on me to be a starting center fielder and traded me away, then, when I’d become a starter elsewhere, they traded to get me back just to put me on the bench again. It was like a cruel joke. But then I looked around the clubhouse and saw a lot of players in the same boat. Tony Womack, Eric Karros, Mark Grudzielanek, Tom Goodwin. We had all been starters, and Baker had his hands full to convince all of us that we shouldn’t be starting now. To his credit, Baker was a magician with people.

Real life had to be managed, too. I had to close out an apartment in Texas, in the middle of a lease. I had to ship my car to Chicago, packed with all the stuff I couldn’t carry in my suitcase, then fly to Dallas to meet the shipping company on an off-day when the Cubs were playing the Astros in Houston. I couldn’t imagine what that would’ve been like if I’d had a family at the time.

Rejoining Chicago was also like moving back home after graduating college. So much had changed. I didn’t know a lot of the players; the staff was different. It was a new culture — I came up in 1996 with the Cubs with Jim Riggleman as manager, someone who I respected and got along with well. Positive, even-keeled, principled. We did not have much success over that year and a half, but he took the time to always tell me where I stood, pulling me aside to let me know, “One day, you will be a starting center fielder — somewhere.” Baker brought in a smashmouth style, dripping with confidence, a master of psychological warfare. For those two stints, I played at the same address, but it was far from the same place.

I eventually found my edge by working with all of the Cubs’ veteran players in a pennant race. Although the Cubs were at .500 when I arrived, we were not far out: Two weeks later, we were in first place. It was my first true understanding that a big part of a manager’s job is filtering out the negativity that can come from a whole bunch of players who think they should have a different role. I was surprised to find myself one of those guys.

It became critical to watch how Dusty ran his ship. Baker was truly the “Godfather of Baseball,” and he gave you straight talk. Months later, I would get the game-winning hit in Game 3 of the NLCS and remind people publicly that I could hit right-handed pitching as a right-handed batter — I pinch hit against a righty in that game. Dusty pulled me into his office after hearing that postgame interview and insisted, “I know you can hit righties.” I got the message, but he dished out the truth and it gave me room to tell mine. I appreciated that.

The days and weeks after my trade had been a crash course in fitting in, something that can be tougher for a set-in-his-ways veteran. I had to let go of the guarantees that put me in the lineup every day and ensured I would have a job the next year, and enter the realm of the unknown. Not knowing when I would get in the game or if we would make the playoffs. I saw the worst-case scenario: not making the playoffs and then not getting a job in free agency. Was it worth it?

In my case, it was, because I would get the only playoff experience of my MLB career. Looking back, despite how it probably hurt my being seen as a starter, I gained something that turned out to be worth my shift in status. A division title and a taste of a championship series.

This week, many players are dealing with change. Even the biggest names — whether it’s a trio of champions in Kris Bryant, Javy Baez, and Anthony Rizzo, all former Cubs now, unsigned and uncertain in new surroundings as they chase the postseason, or Max Scherzer and Trea Turner, in greener pastures as possible three-month rentals. As good as they are, they’re still an injury away from altering their contract opportunities in the offseason. They were settled in their respective cities and fan bases. Families, children, September school enrollment, lost stability — these are no small things, even for players on the top of baseball’s food chain.

Then imagine the young prospects or the journeyman jockeying for playing time, sent back for these household names. Little power, little choice, except to seize the opportunity and make a new home elsewhere. But a new home can be built, and championships can be won.

As I once learned, sometimes you have to embrace the risk. For last week’s traded players, it starts now.