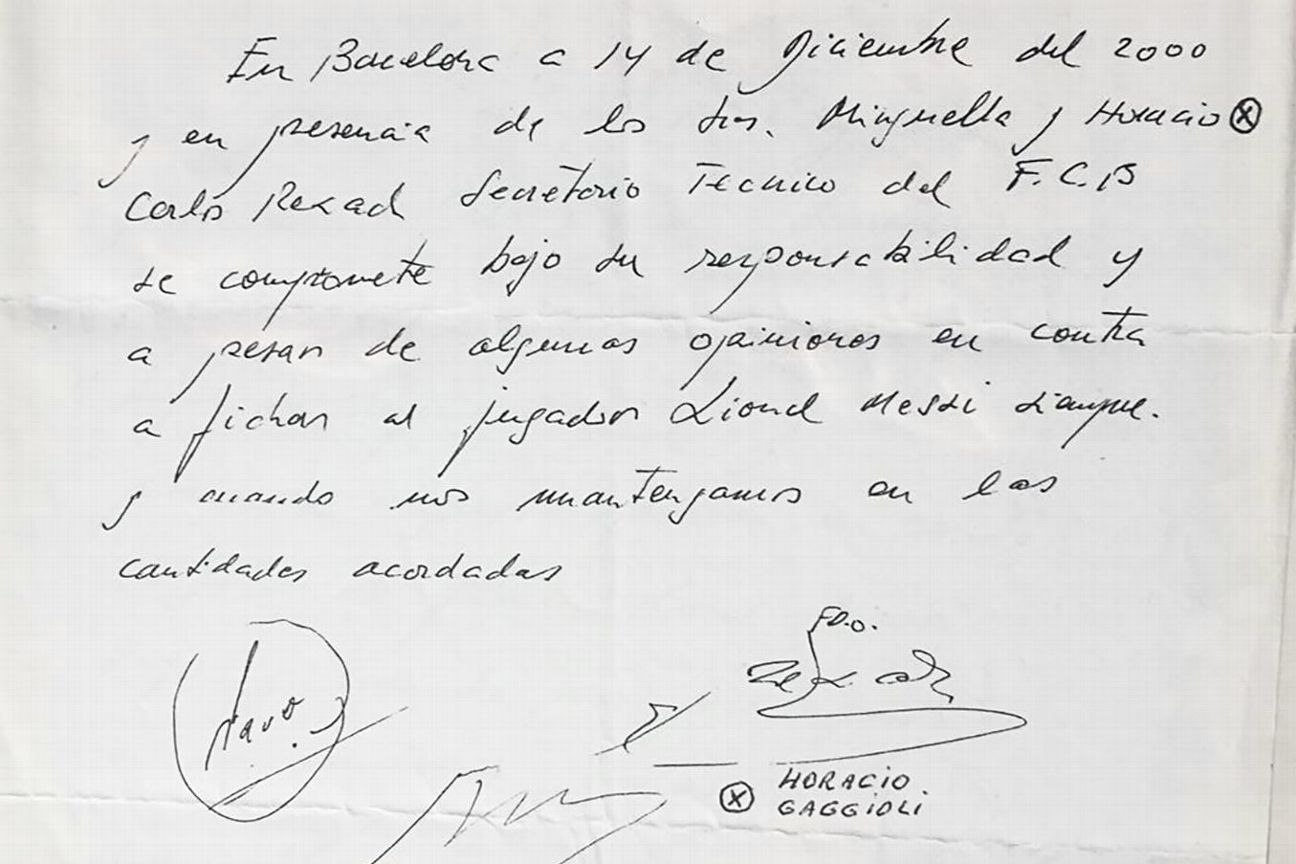

“In Barcelona, on Dec. 14, 2000, in the presence of [Josep Maria] Minguella and Horacio [Gaggioli], Carles Rexach, FC Barcelona’s sporting director, hereby agrees, under his responsibility and regardless of any dissenting opinions, to sign the player Lionel Messi provided that we keep to the amounts agreed upon.”

The above words, scribbled on a napkin following a game of tennis in Barcelona, have gone down in football history. They were hastily written by Rexach, Barca’s sporting director at the time, in an attempt to assure Jorge Messi that the Catalan club was committed to signing his son. Rexach signed the napkin, as did the agents, Minguella and Gaggioli, as witnesses.

– Messi is Barca’s best again vs. Levante

– Messi on cusp of Pele’s record

– Stream ESPN FC Daily on ESPN+ (U.S. only)

Messi’s father had grown anxious about his son’s future because of Barca’s apparent hesitation to complete a deal. There was a debate behind the scenes at Camp Nou about the merits of signing a 13-year-old, but within minutes of watching him during a trial game in Barcelona in September 2000, Rexach was convinced they had to act. When the prospect of Messi moving elsewhere arose, with the threat of Real and Atletico Madrid being offered a chance to sign him, Rexach took matters into his own hands to settle the family’s nerves.

Twenty years later, Messi has scored over 600 goals for Barca and is closing in on Xavi Hernandez’s appearance record for the club of 767 games. (He’s also two goals shy of tying Pele‘s record for the most goals for one club.) He also has been named the best player in the world a record six times and is considered by many to be the best player of all time.

To mark the 20th anniversary of the signing of the napkin, ESPN spoke to the three men who signed it: Rexach, Minguella and Gaggioli, along with Barca’s president at the time, Joan Gaspart, about the events leading up to a moment of improvisation that would change the club’s fortunes over the next two decades.

Reporting by Sam Marsden, Jordi Blanco and Moises Llorens

1:15

Ale Moreno hopes Lionel Messi’s and Cristiano Ronaldo’s high standards aren’t held against them in the future.

Discovering Messi

Messi joined his local team, Newell’s Old Boys, as a 6-year-old in 1994, and videos of his amazing skills at that age have since gone viral. However, news didn’t travel so fast at the time, and he remained relatively unknown outside of Rosario. As he got older, word did get out, but the fact Messi had been diagnosed with a growth hormone disorder — and needed treatment to help his body properly grow and develop — put off clubs in Argentina, including River Plate. The treatment was expensive for a teenager with no guarantees of success. It was an expense they either couldn’t afford or didn’t want to gamble on, and Messi needed a club willing to pay for the treatment.

Messi’s luck changed in 1998, when the Argentine-born agent Gaggioli, a resident of Barcelona for many years, received a call from two contacts in Rosario, Fabian Soldini and Martin Montero. Two years later, Gaggioli, with the help of Minguella — an agent who had worked with Barca on many deals in the past, including the signing of Diego Maradona — and Rexach managed to get the Messi family over to Barcelona.

Gaggioli: Everything started in 1998 when two of my contacts, Soldini and Montero, who had a football school in Rosario, told me about this kid. Messi was 11 when they first called me to speak about him. My idea was to wait a little, until he was 12 or 13, because he was very little at the time. They never hid that he would need injections [to aid his growth]. They kept sending me videos.

Once things began to progress, I organised a meeting in Buenos Aires and [the agent] Juan Mateo came from Porto Alegre. We spoke about getting a video to Minguella to try and get a trial at Barcelona. Messi’s family told Soldini and Montero that they wanted a big club and somewhere the family could all go and live together. That was Barcelona because [I was there], but at the time it could have been a club in Madrid, given I had a proposal to move there that never came to fruition.

By February 2000, I had already seen videos of how Lionel played, and I knew this kid was crazy good. The possibility for me to work in Madrid came up, and I would have offered him to Real Madrid or Atletico, but in the end I stayed in Barcelona and Rexach accepted the proposal of a trial.

Minguella: One of the people I trust most in the world of football has always been Juan Mateo. He was the one who called me on the telephone excited that he’d found an exceptional talent in Rosario, who was playing for Newell’s youth team and how, when he got the ball, he always headed directly for the opponent’s goal. Technology then wasn’t what it is now. Now you can connect in any place in the world and see everything in an instant, but then I had to get them to record some videos and send them to my home.

When I saw the footage, I almost couldn’t believe it. He was a very small player, but with an exceptional talent, who headed straight for the goal with the ball glued to his foot.

Rexach: Gaggioli spoke to me about Messi in Montevideo, Uruguay. I’d been in Brazil watching players and in Montevideo, on the way back to Barcelona, he told me that I had to change my plans and travel to Rosario to see a phenomenon. When I asked about his age and position and he told me 13, my first reaction was there’s no rush … but his enthusiasm when speaking about him took me back. So I made a decision that could have been criticised at the time: I proposed to Horacio that he arrange a trip to Barcelona for the kid and his parents so that we could check him out over a couple of weeks.

I didn’t know anything else of Messi, personally, until I saw him one afternoon — I don’t know the exact date — on the pitches next to the Mini Estadi. A game had been arranged with some of the kids from the youth teams. When Messi arrived in Barcelona, I’d made it clear a kid would be coming for a trial, but I had to leave — I think for Australia — and I wasn’t in the loop until I got back. Later, I heard that he had played in different games, but no one had dared make a decision.

What I will never forget is that a walk of three to four minutes, whatever it takes to walk around the pitch, took me 15 minutes because I was stunned and excited watching him, seeing what he did with the ball, his movements, his dribbles and his vision. I knew that was him, without anyone telling me, because he was the smallest on the pitch by a long way and I could see something very different in him. I got to the bench, sat down and I told the two coaches that were there: “Sign him. Don’t even think about it. And if anyone asks, tell them it’s my decision.”

Gaggioli: When I saw him for the first time, I didn’t realise how little he was. He came to Barcelona for the trial on Sept. 16 until Sept. 30. Jorge Messi, Soldini and I watched the trial games together. Lionel stood out straightaway. He touched the ball like no one else. There were nerves, but Lionel soon dispelled them. It was a wonderful experience and Rexach said that he was already convinced that the club had to sign him.

Gaspart: I didn’t know who Messi was. It would be easy to say I did, and that I fell in love from the first day, but that’s not the case. Rexach spoke to me about Leo, he deserves all the credit. He came to me and said that we cannot let this exceptional kid who has come over from Argentina escape. He said he was different to anything he’d ever seen. And when a sporting director of Rexach’s standing says that … I didn’t just give him permission, I encouraged him to get it done.

And I repeat: [I did it] without knowing anything about Leo.

0:51

Sergino Dest believes Barcelona have “got their spirit back” ahead of their visit to Cadiz.

The risk of losing Messi

Despite Rexach’s conviction that Barca should sign Messi, the club took its time after that September trial. There were doubts about investing in someone so young. Messi and his family were between Barcelona and Buenos Aires, and as time passed, with no news from Barca, they began to get anxious.

As the Christmas period approached, those involved in helping bring Messi over to Spain began to think about taking him to other clubs. Real Madrid and Atletico Madrid were mentioned.

Gaggioli: Rexach had already decided [to sign him], as had the late Joan Lacueva, who ended up paying for the start of his hormone treatment, but the club hadn’t decided. They said it was crazy to sign Messi. Things weren’t going well at Barcelona at all and the club was close to bankruptcy. Montero came in November to try and sort the problems, but he didn’t manage to. Montero then called me and told me to talk with Rexach and warn him that we can’t hold on any longer. And he told me that if we weren’t going to sign, Messi would go for trials with Real Madrid or Atletico.

Rexach: I don’t know if there were other teams interested at the time, I don’t think so. We had here, at the club, a kid very different to anything we had seen before. It was, I don’t know, like a gift, a unique chance for as much as there was risk involved. They said to me at the club, “Listen, Charly, he’s 13 years old and we don’t know what can happen in the future …” They didn’t want to take a risk on such a young kid. But I knew we had to sign him to stop him going elsewhere and then regretting it.

Minguella: River Plate had him on trial for a couple of days, but decided not to sign him in the end. For that reason, when the chance to travel to Barcelona came up, the player’s dad didn’t have much to think about.

Part of the trial was a game with kids of Messi’s age and a team from [the next age bracket above]. It was arranged after we spoke with Rexach about the kid coming to Barcelona. The best thing they could do was watch him. Charly had the president’s confidence and is a legend at Barca, so there was no one better than him to give [Messi] the once-over.

Rexach reacted the moment he saw him play. After a few minutes, he said he had to be signed, that he was unique. Also at that game was Quimet Rife and various ex-Barca players who were working in the academy at the time. Messi was different to the rest and it confirmed what we had seen in the videos Juan Mateo had sent me from Argentina: he always looked to get to goal.

Gaspart: I didn’t know anything about the trial and didn’t even consult anyone after speaking with Rexach. I already said it was his decision … Well, the final word had to be mine, as the president, of course, but the credit is all Charly’s.

Messi’s signing came a few months after [Luis] Figo’s exit, which was really hard for the club and deserved a book of its own. Everything that happened in that August I would not wish upon anyone, and as you can imagine, at that moment, Messi was not a priority for the club.

I do remember the logistical conditions were different because the father, Jorge, wanted Leo to live in a flat with him and not in La Masia with the rest of the kids in the academy. As an exception, Rexach told me it could be done, that we couldn’t be getting tangled up in minor issues and that we had to do it.

Signing the napkin

By the middle of December, Messi’s dad, Jorge, was particularly nervous. The lack of news out of Barcelona was leading him to believe they weren’t willing to sign his son. Sensing that the club could miss out on a once-in-a-lifetime player, Rexach stepped in to ensure that Messi did not go elsewhere.

Rexach: Jorge thought [Barca] were stalling. I wasn’t there and don’t know exactly how things were, but when I met with Jorge I realised he wasn’t clear on anything. I suppose he didn’t trust [Barca] and he seemed desperate, so one night I met with Minguella and Horacio at the Pompeya tennis club and, speaking with Jorge on the phone, he told me, “If this isn’t sorted soon, we’re going. I have to return to Buenos Aires and I don’t see anything happening.” That was when, thinking on my feet, I decided everything.

Why a napkin? Because it was the only thing I had available to hand. I saw the only way to relax Jorge was signing something, giving him some proof, so I asked for a napkin from the waiter and I wrote: “In Barcelona, on 14 December 2000 and the presence of Messrs Minguella and Horacio, Carles Rexach, FC Barcelona’s sporting director, hereby agrees, under his responsibility and regardless of any dissenting opinions, to sign the player Lionel Messi, provided that we keep to the amounts agreed upon.”

I told Jorge that there was my signature and that there were witnesses, that with my name I would take direct responsibility, there was nothing else to talk about and to be patient for a few days because Leo could already consider himself a Barca player.

Minguella: We met at the Pompeya tennis club in Montjuic in Barcelona. We were chatting for a while after playing a game of tennis. Horacio was also there. We reached the conclusion that something had to be done. It was genius from Rexach, with no paper to hand at the tennis club, grabbing the napkin, writing the contract and all of us signing it.

Straight after that, I spoke with Jorge Messi, who was at the Plaza Hotel in the city with Leo, to confirm one of the president’s men had signed a document and that the kid was here to stay. The Messis were getting desperate given Barca’s silence, but at that moment everything was cleared up.

Gaggioli: The napkin was a valid document legally, according to what my lawyers told me, and it changed everyone’s life. It’s now guarded in a bank in Andorra — it’s a historic document and must be protected. That said, it should also be noted that since that document existed, Barca sent a letter inviting the family to come to Barcelona. Joan Lacueva sent a letter of 10 lines saying that in February 2001, the whole family should travel to Catalonia.

Gaspart: The napkin was a moral way of making it clear to Jorge that there was nothing to worry about. Officially, it didn’t serve as anything, but it was the step before signing the first contract, which [former Barca vice president] Paco Closa did.

Debut and treatment

The napkin was just the beginning of the end of the saga. It would be almost another month until Messi was officially signed as a Barca player. He wouldn’t be able to make his competitive debut until March due to registration issues.

Wearing the No. 9 shirt in a game against Amposta, he scored on his first official appearance for the club. Everyone at the club soon realised the caliber of player they had on their hands and it wasn’t long before other European heavyweights were trying to lure him away. Messi, though, remained loyal to Barca, grateful that they’d agreed to fund his hormone treatment.

Messi’s treatment involved injecting his own legs with human growth hormone each night. The full cost of the treatment was reported to have been around €1,000 per month, although neither the club nor Messi has confirmed the figures involved.

Rexach: He didn’t make his debut for a while because he was foreign and could not play official matches until his father was registered in the country. We had to sort the paperwork so that he could play, but after the napkin I was relaxed, and so was Jorge.

Minguella: There were some small bureaucratic problems that were solved in March, the month he made his debut. He was foreign and under 18, so he had to have authorisation. Despite training with the U13 A-team when it would have been more normal to be with the U15 B-team, he had to make his debut with the U13 B-team.

Gaggioli: Newell’s had refused to pay for the hormone treatment, like River Plate. Lacueva paid for the initial phase of the treatment and after that Barca took charge of everything. Once he started to play regularly [for Barcelona], all the big clubs started to call, like Juventus, Inter Milan, Liverpool, Real Madrid, although Arsenal were closest to signing him. We even had dinner with Arsene Wenger. It was around the time Cesc Fabregas, Messi’s close friend, moved to Arsenal.

Rexach: The hormone treatment? Look, I took charge of the signing — everything else was the club. Obviously there was a cost involved, but it wasn’t excessive and I didn’t worry about it. I said, “He’s signed and now you can take care of the rest,” making it clear [the club] had to take responsibility.

Gaspart: Nothing special happened with the growth treatment, the hormones. Don’t pay attention to what people can say with bad intentions. The signing was approved with the special connotations [relating to the treatment] and from there, Messi had a normal day-to-day life at the club. What I do suspect is that for a certain amount of time, another club wanted to get their hands on him. It’s not necessary to say who. [Real Madrid?] I think it’s obvious, of course.

I didn’t get the chance to enjoy Messi as president. I wasn’t lucky enough to benefit from him, or from players like Andres Iniesta, Victor Valdes, Xavi and Carles Puyol, even though some had debuted in the first team and I was especially careful to ensure that Puyol and Xavi stayed at the club when they could have left and to reason with [Louis] van Gaal when he wanted to kick out Valdes. Taking care of the homegrown kids and the players from the academy is fundamental for the club.

I am satisfied that the relationship the Messis, Jorge and Leo, have with Barca has always been very close. They understand the chance the club took on Leo and their gratitude has been very evident.