Every year, two Hall of Famers are born.

OK, it’s not quite that precise, but as an average, it works out: 20 future baseball Hall of Famers (from the Negro Leagues and the American and National Leagues) were born in the 1910s, and so on from there:

1920s: 17 Hall of Famers born

1930s: 24

1940s: 18

1950s: 21

1960s: 19

Average: 19.8 per decade

Two per year creates a nice symbolic standard, doesn’t it? To the question “What’s a Hall of Famer?” we can come up with any number of esoteric definitions. But “one of the two best baseball players born that year” really gets to the heart of it — especially when it splits, as it so often does, into one pitcher and one batter, the yolk and albumen in baseball’s egg:

1920s: 10 hitters, 7 pitchers

1930s: 17 hitters, 7 pitchers

1940s: 10 hitters, 8 pitchers

1950s: 15 hitters, 6 pitchers

1960s: 12 hitters, 7 pitchers

I bring this up because this year, Tim Hudson and Mark Buehrle will be on the Hall of Fame ballot for the first time. Neither will be inducted in 2021 — or, probably, ever — but voters should really consider each of them. As it stands now, and as it threatens to stand for a very long time, there are only two Hall of Fame pitchers who were born in the 1970s. It’s a very conspicuous drought, and it probably tells us a lot more about an era of baseball than it tells us about the actual talent of baseball pitching that 1970s date nights produced.

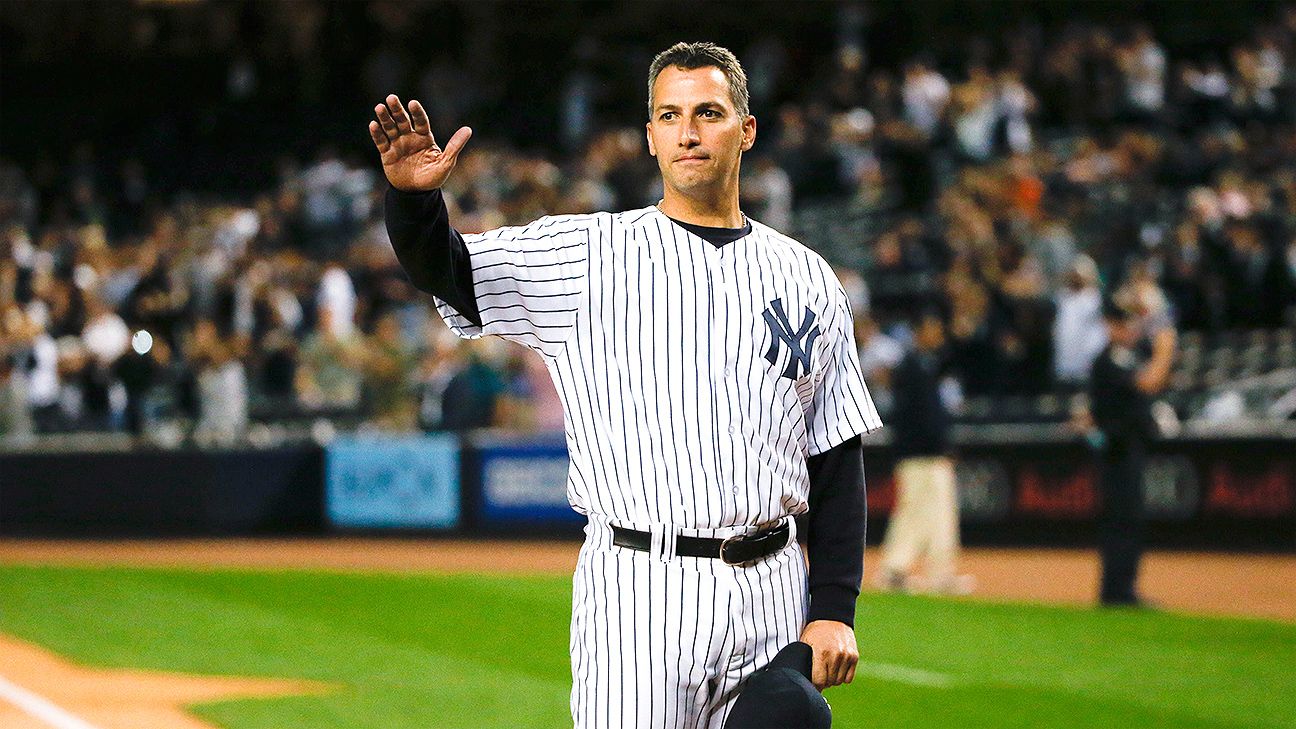

But more than Hudson or Buehrle, they should definitely check the box next to Andy Pettitte. That’s what this is really about: Everybody should vote for Andy Pettitte.

To be clear: There’s a good case for Pettitte that doesn’t involve the decade in which he was born. Pettitte’s WAR — 60 at Baseball-Reference, 68 at FanGraphs and 61 at Baseball Prospectus — is around the lower tier of inducted Hall of Famers and near the very top of the non-HOF tier, which makes his case the very definition of arguable. His FanGraphs WAR is higher than Tom Glavine’s or Roy Halladay’s (to compare him to contemporaries), and his Baseball-Reference WAR is about level with Juan Marichal and Don Drysdale (to compare him to his ancestors).

If his WAR gives us a reason not to discard him as a no, his postseason performance gives us the reason to elevate him to a yes. His postseason win probability added is sixth all time. Cooperstonian Jack Morris’ postseason résumé was (rightfully) a big part of his Hall of Fame case. Pettitte threw three times as many postseason innings as Morris, with a comparable ERA and three times as many wins. Pettitte’s record 19 postseason wins are undeniably the benefit of playing in an era of expanded playoffs, but it’s also a record that’ll probably never be broken, at least until the definition of the win is changed. (Nobody else has more than 15, and starters today don’t regularly pitch deep into postseason games the way Pettitte did. This year’s starters went six or more innings in 26% of postseason games, while Pettitte did so in 80% of his. He went a full seven innings 19 times. No starting pitcher did that twice this fall.)

But not all yeses are urgent enough to write about. I’d put Kenny Lofton in the Hall of Fame, but I never wrote a column about it. What gets Pettitte the full treatment goes back to the year of his birth: 1972, right smack in the middle of our conspicuous Hall of Fame pitcher drought. If you think that drought is just a coincidence, then there’s nothing to rectify. I just don’t think it’s a coincidence.

Andy Pettitte debuted in the majors in 1995. A few things were happening in 1995:

1. It was the third year of baseball’s offensive explosion. There were more runs scored in 1995 than there had been in a full season since 1938. In 1996, offense went up even higher, and it didn’t go down for a long time. For the first seven years of his career, Major League Baseball was in the longest sustained offensive boom in its history. Before Pettitte’s career, there had been one season in the previous 50 in which teams averaged more than 4.75 runs scored per game. The league topped that in each of the first eight seasons of his career.

2. Pitchers were increasingly being pushed to throw harder. When Ben Lindbergh studied thousands of scouting reports from that time, he found that leaguewide velocity rose every year from 1995 on. More important, by matching clubs’ overall assessments of pitchers to their fastball velocities, Lindbergh found evidence that velocity was increasingly prioritized by teams. Pitchers were both throwing harder than they ever had and they were being encouraged and incentivized to throw harder still.

3. Home runs were out of control. The strike-shortened 1994 season was only the second year in history in which teams hit more than one homer per game. The league did that every single year afterward, setting three new leaguewide records in Pettitte’s first six years.

4. Batters were becoming more patient — or pitchers were becoming more cautious, or higher strikeout totals were pushing counts deeper, or a combination of all three. But at-bats were lasting longer: 3.7 pitches per PA when he debuted, up from 3.58 a half-decade earlier.

So put it together: longer and more high-stress innings, comprising longer plate appearances — because every hitter in the lineup was a threat to homer — and more pitches that had to be thrown at maximum effort. And pitchers were doing this all while throwing harder than pitchers ever had before, for teams that were encouraging more velocity than they ever had before. It was a great way to get hurt.

There were, of course, great pitchers during this time: Greg Maddux (born 1966), Roger Clemens (1962) and Randy Johnson (1963) are three GOAT contenders, and they were all active in the middle of this. There were Tom Glavine (1966) and John Smoltz (1967), plus non-HOFers Curt Schilling (1966) and Kevin Brown (1965). But those pitchers were all well established by the time these trends took hold. Even Mike Mussina (born 1968) was 24, with 330 big league innings under his belt, by the time the switch flipped from “pitchers league” to “hitters league” in 1993.

My hypothesis is that it was hard to pitch in those years, but it was extremely hard to be a young pitcher. They were being asked to pitch at high effort for long innings and with men on base. They were being asked to get their feet wet against lineups full of steroid users and to maintain their confidence while getting their teeth knocked in. If you were a young pitcher, this would be the worst league to debut in. And if you were a pitcher who was a little bit more prone to injury, as young pitchers on balance are, then this would be the worst league to stay healthy in.

So compare Pettitte not to Maddux or Clemens but to the pitchers who had to do what he had to do: who had to make it out of the minors during this era, who had to debut in the mid-’90s in their early-to-mid-20s, and who had to survive their first half-dozen seasons in the middle of an offensive and velocity explosion.

If we agree that those pitchers — the ones born in 1972 or thereabouts, the ones drafted in 1990 or thereabouts, and the ones who debuted in 1995 or thereabouts — are Pettitte’s true contemporaries, he starts to look really good. Only two other pitchers born in the 1970s — Pedro Martinez and Roy Halladay — had more career WAR than he did. (And note that Halladay very nearly lost his career during this era, getting sent back to Single-A after posting the worst ERA in major league history when he was 23.)

Sixty WAR might not be all that exceptional for the generation born in the 1960s, in other words, but it’s darned near the top of the scale for a pitcher born in the 1970s.

But if the case for Pettitte is “60 WAR is really amazing for a modern pitcher,” then what do we do about the inconvenient facts of Max Scherzer, Justin Verlander, Clayton Kershaw and Zack Greinke — all born in the mid-1980s, all likely to challenge 70, 80, maybe 90 career WAR?

It’s true that many of them were also brought up with the same challenges we highlighted for the pitchers born in the 1970s: longer at-bats, more emphasis on strikeouts and velocity, relatively high offensive environment, not to mention having been raised pitching year-round in travel ball and showcases, which many consider dangerous for young arms. It’s probably true that pitching is just as hard on the young arm today as it was when Pettitte and his peers were young arms. But by the 2000s, medical care was catching up to the needs. Shoulder strengthening dramatically reduced shoulder injuries, Tommy John rehabs were more effective and so on.

You can see this in the success rates of pitching prospects throughout the 1990s and beyond. I once found that the average top-50 pitching prospect in 2008 produced about four times as many WAR, and threw about twice as many innings, as the average top pitching prospect in 1993. (These weren’t one-year flukes — the trend was pretty consistent.)

All of this is to say that it’s really hard to put Pettitte’s 61 WAR into perfect context. But it’s already a competitive number, bolstered by postseason stardom and his key role on a postseason dynasty, which make his career quite consequential. If we adjust for his birth peers, the case that he was an extraordinary outlier — as all Hall of Famers are — seems sturdy.

The case against him:

1. He did PEDs. Fair! If that’s a blanket disqualifier to you, he’s disqualified. But so far 60% of voters support Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, and nearly 30% support Manny Ramirez — who was suspended twice after the league began testing. So we know that, at the very least, 60% of voters are willing to vote for a PED user. And at least 30% are willing to vote for a PED user (even a repeat PED user) who isn’t arguably the greatest hitter or pitcher ever. Clearly, the PEDs are not primarily what kept Pettitte to about 10% in his two turns on the ballot.

2. He didn’t have the accolades of a superstar during his career: No Cy Young, only three All-Star appearances. Also fair! But his Cy Young shares are consistent with plenty of other Hall of Famers (e.g. Mike Mussina, Bert Blyleven, Don Sutton, others). His lack of All-Star appearances probably reflects a quirk of his: He was much better in the second half than he was in the first: 4.06 ERA, .589 winning percentage before the break, 3.60 ERA, .670 winning percentage after. Odd, but not in any way a factor in his value to his club. The point of a career isn’t directly to make All-Star games.

That’s pretty much it, along with the fact that there are some better pitchers who aren’t in the Hall — but, then, there are a bunch of worse ones who are. There’s a pretty good chance that nobody born after him will ever top his 256 wins, especially if he can hold off Clayton Kershaw.

At the moment, the number of Hall of Fame hitters born in the 1970s is also low, by historical standards — there are five in so far — but that’ll change in coming years. Ichiro Suzuki and David Ortiz will both likely walk in. Adrian Beltre is going to be automatic. Alex Rodriguez is too, unless voters punish him for his PED suspension and multiple PED scandals. That’d make nine, and it probably won’t stop there: Scott Rolen’s vote totals are going up exponentially, Carlos Beltran should make it, and people will write columns on behalf of Chase Utley, the NL’s second-best player for a half-decade. Three other players on the ballot — Andruw Jones, Todd Helton and Manny Ramirez — have been getting more support than Pettitte. The hitters will be fine.

But no pitcher from the decade currently gets the same support, or looks likely to without some attempt at balancing the era. If people won’t vote for Pettitte (60/68 WAR), they probably won’t vote for Mark Buehrle (60/52) or Tim Hudson (58/49). They already passed on the short but brilliant career of Johan Santana (52/46), and the slightly longer, slightly less brilliant career of Roy Oswalt (50/53). They’re not flocking to the post-Mariano Rivera relievers, Billy Wagner and Joe Nathan. That leaves … nobody. There’s nobody else.

And even the first third of the 1980s might go unrepresented, unless CC Sabathia gets in. Having read this article, you probably won’t be surprised that I think Sabathia should get in. Fortunately, I think he actually will get in. Also:

Pettitte: 60 B-Ref WAR, 68 FanGraphs WAR, 256 wins, 117 ERA+

Sabathia: 63 B-Ref WAR, 67 FanGraphs WAR, 251 wins, 116 ERA+

But look, somebody’s got to be in the Hall of Fame besides Roy Halladay and Pedro Martinez. More than 2,000 days separated Pedro’s birth and Halladay’s, and more than 2,000 days separated Halladay’s birth and Justin Verlander’s. Almost six years, a very long time. Pettitte is clearly the best pitcher the world produced in the first period, as Sabathia was clearly the best pitcher the world produced in the second. Put ’em both in.