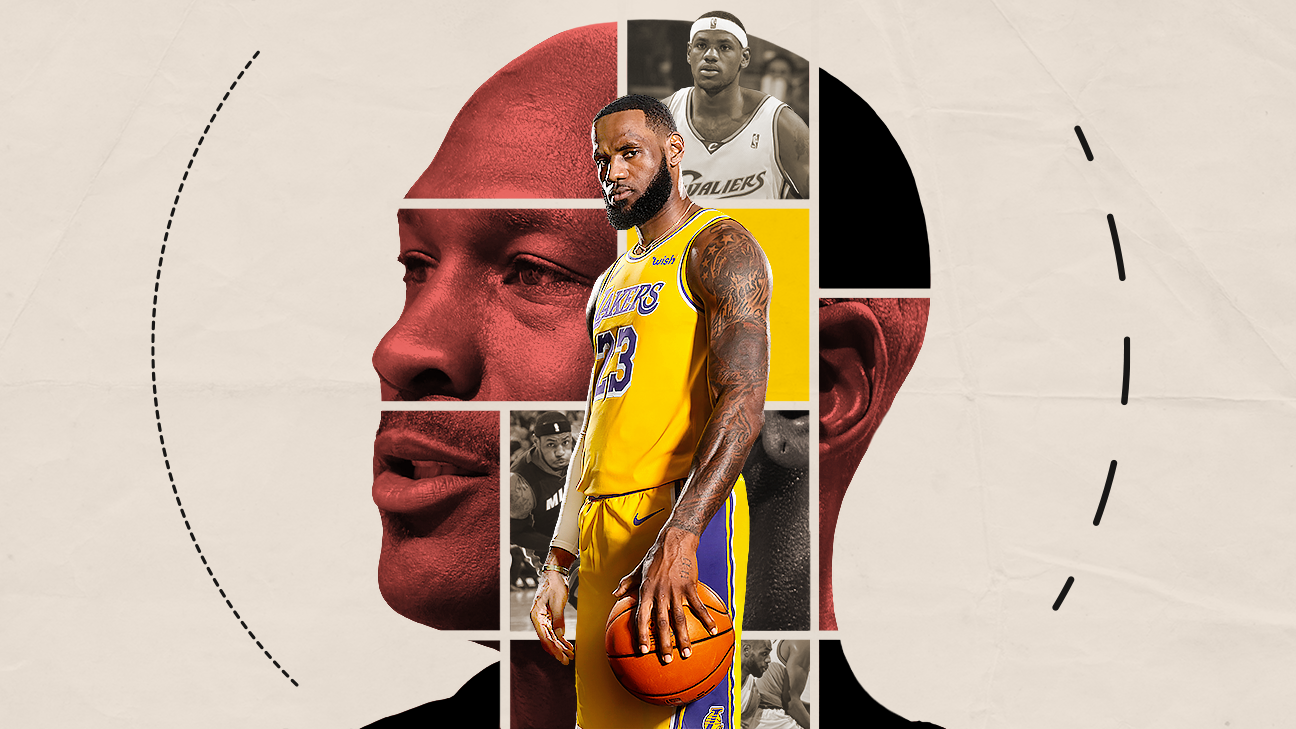

There is an amazing clip from ESPN’s The Jump in April 2018, the day after LeBron James‘ fourth career postseason game-winning buzzer-beater — a 3-pointer that put his Cleveland Cavaliers up 3-2 in their first-round series against the Indiana Pacers.

That gave LeBron one more postseason walk-off shot than Michael Jordan, who of course played fewer playoff games than LeBron — 81 fewer after James and the Los Angeles Lakers clinched the franchise’s 17th NBA title Sunday. Rachel Nichols, host of The Jump, displayed Jordan and James’ respective numbers on go-ahead shots in the last five seconds of the fourth quarter and overtime in playoff games. The numbers were basically identical. Nichols prodded Tracy McGrady and Scottie Pippen: Was Jordan really more “clutch” than LeBron?

The reactions of Pippen and McGrady are telling. They can barely express how preposterous they find the question. Pippen smiles, sighs, and tells McGrady to answer first. They nominate players they would trust more than LeBron with the game on the line: Reggie Miller, Paul Pierce, Kobe Bryant, Joe Johnson.

“The reason being,” McGrady says, “LeBron’s first thought is, ‘I’m gonna make the right basketball play.'”

“Right,” Nichols replies. “Which is part of being clutch.”

“We’re talking about making the shot,” McGrady responds. “Those [other] guys are, ‘I’m taking the shot. I’m not looking to pass.'”

Nichols refers to the statistics on the screen: “The numbers say [LeBron] has done it more often than Jordan.”

Pippen dismisses the numbers as merely proof that LeBron has played too many close games. “I like winning by 10,” he says. “LeBron is not the guy that wants to take that last shot.” Nichols gives it one more try: “But he’s done it more than the other guy!”

McGrady and Pippen don’t care. The discussion is absurd to them. Jordan has something LeBron lacks, and will remain untouchable, more god than human.

And I get it. I came of age as a fan in the Jordan era. Lots of team executives in that age cohort — dispassionate talent evaluators in their work — use different language and standards discussing Jordan’s greatness. It was something we felt. He was indomitable in a way James can never be.

The aura of invincibility did not cocoon Jordan only in hindsight. He felt unbeatable in real time. The Chicago Bulls were invincible in two of Jordan’s six title runs. No one tested them in 1991 and 1996 — the first titles of Chicago’s unprecedented separate three-peats.

But in 1992, the New York Knicks took arguably the best Jordan team ever to seven games in the second round. The Portland Trail Blazers had the 1992 Finals knotted 2-2 with Game 5 in Portland. New York led the 1993 conference finals over Chicago 2-0. That season’s Phoenix Suns, with the MVP in Charles Barkley, gagged away Game 6 in Phoenix — with Game 7 looming there — before John Paxson’s title-clinching triple. (Jordan scored every Chicago point in that 4th quarter — all nine — before Paxson’s shot.)

The Utah Jazz evened the 1997 Finals 2-2, and hosted Game 5 — the Flu Game — which the Bulls eked out by two. The 1998 Indiana Pacers had the Bulls on the ropes in Game 7 of the conference finals.

Those were moments of dire uncertainty against several great teams at their respective apexes. They did not feel uncertain to a lot of contemporary observers (this one included). Jordan was inevitable.

He was perfect: 6-0 in the Finals, and into retirement — coaxed by Jerry Reinsdorf’s refusal to honor a champion — before the Bulls could decline. Could Chicago have four-peated in 1999? Other what-ifs dare you to imagine an imperfect Jordan: Would Chicago have lost one (or two) Finals against the mid-1990s Houston Rockets had Jordan not left to play baseball? Do the Bulls manage that second three-peat if Jordan doesn’t refresh himself those two years? Some ex-Bulls have cautioned against assuming an uninterrupted run of dominance. (Steve Kerr has called the notion of eight straight titles “preposterous.”) What if Shaquille O’Neal stays in Orlando — beefing up the East during Chicago’s second three-peat?

What if there is no fluke salary cap spike enabling Kevin Durant to sign with the Golden State Warriors in 2016? The 2016-17 Cavaliers were the best Cleveland team of LeBron’s career. How do we look at LeBron’s Finals history if those Cavs repeat against the non-Durant Warriors? What happens in 2018? Does Kyrie Irving stay?

That is alternate history. Truth leaves Jordan perfect, and LeBron now 4-6 in Finals. The sheen of Jordan’s perfection glows brighter with time. It overwhelms and distorts the discussion of whether James might surpass him as the greatest player in modern history — or if he already has.

Three of LeBron’s six losses came against the Warriors — two to Durant superteams, and a third in which both Irving and Kevin Love were injured.

Another came in 2007, when James in his fourth season dragged an underwhelming Cleveland team into the Finals against the veteran San Antonio Spurs. It was not a fair fight. Young LeBron underwhelmed: 22 points per game on 35.6% shooting. But he was transcendent advancing to the Finals much earlier in his career than Jordan.

That leaves two defeats: 2011 against the Dallas Mavericks, and 2014 against the Spurs again.

The 2011 series is the stain. LeBron was bad — passive, uninvolved. He scored eight points in one game. Jordan’s career low in the Finals was 22. James’ failure will always mar the perception of him relative to Jordan, even on some subconscious level. It changed the way we looked at LeBron. He buckled in a very human way. Jordan seemed inhuman — impervious to fear. The 2011 Finals mortalized James. He cannot erase it, outrun it.

San Antonio was the better team in 2014 — an upper-echelon champion by postseason scoring margin. Even so, we never saw a peak Jordan team get rolled like that — 4-1, blowout after blowout.

At least not after 1988, when the Detroit Pistons bullied Chicago 4-1 in the conference semifinals. The Bad Boys eliminated the Bulls again in 1989 (six games) and 1990 (seven games) on their way to consecutive titles. Jordan lost one series after that: in 1995 against the Orlando Magic, weeks after returning from baseball.

There is an appealing linearity to Jordan’s career that colors the GOAT discussion. Jordan lost to champions — enduring conference rivals — until he learned to unseat them. He remained with one team almost his entire career.

LeBron upended norms about “loyalty” and teambuilding. He took an active role in building two Big 3s and now a colossal Big 2. That doesn’t necessarily make his top-heavy supporting casts any better than Jordan’s, considering the depth and defense surrounding the Bulls’ star duos and trios.

After LeBron’s first jump — to Miami — he had no Eastern Conference rival on par with the 1980s Boston Celtics and Pistons. Boston aged fast. Derrick Rose‘s knee injury undid the Bulls. The Paul George/Roy Hibbert Pacers stepped into the void, and pushed Miami — including in a seven-game conference finals in 2013. But they never profiled as a truly elite team.

That 2013 Miami-Indiana series stands out on LeBron’s record, too. The Heat that season coalesced into a historic juggernaut. They won 27 straight games. They were on a 45-3 devastation tour entering that Indiana series. They finished the last two rounds 8-6, and teetered on the brink in the 2013 Finals against San Antonio before Ray Allen’s corner 3.

That 8-6 record blotted out LeBron’s best chance before now to stamp one season of Jordanesque inevitability. Almost every top-10 all-time player has one postseason when it feels impossible to beat his team. LeBron never had that. Does going 16-5 in the Orlando bubble count? Did the Lakers give you that feeling of inevitability?

All of this — the 2011 Finals, LeBron’s sometimes pass-first nature, the perceptions of their respective personalities and career paths — has probably obscured how monstrous LeBron’s big-game crunch-time record is. Game 5 against Miami is a microcosm. LeBron scored 40 on 15-of-21 shooting, including two rampaging go-ahead, super-clutch layups in the last 100 seconds. And yet: Danny Green missing a potential championship-winning triple — off a pass from LeBron — shoved those baskets into the background. If Green hits, LeBron is a hero — author of his own Jordan-to-Kerr pass. Green missed; critics wonder.

Perceptions of their divergent leadership styles infect the analysis of their approach to crunch time. Jordan was aggressive. He browbeat teammates, fought them, prepared them for the postseason hothouse. LeBron was (is?) passive-aggressive. Jordan is the alpha competitor. LeBron is the over-thinker.

Some ex-teammates who were not fond of Jordan’s tactics have acknowledged he might have helped steel them. But there is mythmaking at work. Did Kerr need Jordan to punch him to hit crunch-time jumpers? Many of those teammates have said Jordan’s upbraiding would not have had its intended effect without Pippen’s nurturing leadership counterbalancing it.

But McGrady and Pippen are onto something vaguely real when they suggest LeBron’s big-shot profile feels different than Jordan’s — regardless of whether that feeling leads toward greater truth. All five LeBron buzzer-beaters, including one against the Raptors 10 days after that segment of The Jump, came before the Finals. Four came in seasons when LeBron’s team lost the Finals. There is no narrative thread connecting them to ultimate glory. Human memory requires through lines. Without them, some shots recede.

Jordan has two of the NBA’s rare walk-home shots — including the levitating dagger over Craig Ehlo, a basket so majestic and portentous it is known simply as The Shot. (The other came four years later in a sweep, also over the Cavs.) He won a Finals game — Game 1 in 1997 against Utah — with a buzzer-beater. He capped his Bulls career a year later with something close to a walk-home shot over Bryon Russell.

LeBron’s most famous Finals shot might be a long 2 to put Miami up four with 27.9 seconds left in Game 7 against San Antonio in 2013. It doesn’t have the resonant splendor of a typical championship-clincher; the Spurs almost conceded it, as they did most LeBron jumpers. (James then sealed the championship with a steal.)

His most famous Finals moment is a defensive play — his epic chase-down rejection of Andre Iguodala in the frantic waning minutes of Game 7 in 2016 against the Warriors. On Cleveland’s most important offensive possession of that game, LeBron ceded center stage to Irving. Jordan owned center stage, always. He passed only when the defense dictated it.

Maybe LeBron doesn’t have a flashbulb Finals shot. Look deeper, and you see a volume of high-stakes, late-game dominance to rival Jordan.

The fourth quarter and overtime of Game 6 in 2013 — with Miami down 3-2 against San Antonio — is one of the greatest all-time stretches of pressurized athletic performance. LeBron scored or assisted on 29 of Miami’s final 38 points (if you count LeBron passes that led to shooting fouls), including the first 17 as the Heat erased a 10-point deficit. He was everywhere on defense. He single-handedly willed the Heat back. (He also committed two addled turnovers in the last minute of regulation that nearly cost Miami the game.)

He drained the must-have triple with 20.1 seconds left in regulation before Allen’s equalizer — plus a floater with 1:43 left in overtime to give Miami the lead. In Game 7, LeBron canned three long 2s in the last 5:40 — including the series-clincher.

It has been overshadowed by Irving’s shot and LeBron’s block, but James scored 11 of Cleveland’s 18 points in the fourth quarter of Game 7 in the 2016 Finals — including eight straight in the middle to turn a four-point deficit into a two-point Cavs lead.

James shot 0-of-4 in the wild last 4:15 of that game. Fine. Everyone was missing; the score froze at 89-89 for almost four straight minutes. LeBron barely missed a dunk over Draymond Green — who fouled him hard — with 10.6 seconds left that would have broken the Internet and gone down as the most memorable basket of LeBron’s career. (He iced the championship at the line.) His back-to-back 41-point performances — on 32-of-57 combined shooting — in Games 5 and 6 may not get their “clutch” due because the Cavs had the audacity to blow out the Warriors.

LeBron won a conference finals game — Game 1 against Indiana in 2013 — with a layup at the buzzer. He won another — Game 2 against Orlando in 2009 — with a triple at the buzzer. In one 45-point, 15-rebound masterpiece in the 2012 conference finals, LeBron ended the Celtics and maybe saved the Heat Big Three.

Game 1 of the 2018 Finals against Golden State might be the greatest game of LeBron’s life, and it includes the kinds of Jordanesque last-second Finals baskets that for weird reasons don’t shine as clearly on his playoff résumé. He bulldozed for two go-ahead layups in the last minute of regulation. When the Warriors threw this defensive alignment at LeBron in the final seconds, he lasered an impeccable pass to George Hill:

The Warriors fouled Hill. He made the first to tie it. He missed the second, and JR Smith happened. Golden State rolled in overtime, and swept. Those results render LeBron’s performance more footnote than is fair: 51 points, 8 assists, and 8 rebounds on 19-of-32 shooting — including 13 points on 6-of-7 shooting in the fourth quarter. Perhaps the best team ever built had no answer for LeBron alongside Jordan Clarkson, Kyle Korver, Jeff Green, and Larry Nance Jr. LeBron exceeded 40 points in eight of Cleveland’s 21 playoff games in 2018.

Jordan’s clutch dossier is impeccable. We rewatched it with “The Last Dance.” There are plenty of misses, including free throws, but no player has ever matched Jordan’s combination of late-game volume and efficiency.

But LeBron is closer than it might feel like.

Look again at that photo of LeBron surveying Golden State’s defense. Durant and Green are not guarding people. They are guarding space. That was against the rules in Jordan’s career. Where is James supposed to go? Would you have him barrel into four bodies and throw up some flailing floater?

Most of the discussion of the differences between the Jordan and LeBron eras has focused on the physicality of the 1980s and 1990s. Perimeter defenders hand-checked Jordan. The Pistons body-slammed him, and got penalized with common fouls. Perhaps big men had it easier then, as John Hollinger of The Athletic wrote Friday in noting how Jordan towered over other 1990s perimeter stars — though Larry Bird and Magic Johnson ruled the 1980s.

The early-2000s ban on hand-checking opened the drive-and-kick game — LeBron’s wheelhouse. It hastened the rise of the 3-pointer. James has made 1,560 more 3s, accounting for more than the total scoring gap between them (about 3,500 points in LeBron’s favor, regular season and playoffs combined). Jordan would have taken more 3s today. He would have generated more as a passer.

But the abolition of illegal defense has turned isolation basketball into a chore. Jordan either went one-on-one, or drew hard double-teams. Stars don’t go one-on-one anymore. They go one-on-team, with layers of help blocking every corridor. LeBron’s era might be softer, but it is also more strategically complex. Would Jordan’s miniscule turnover rate be higher today?

The statistical comparison is now a wash. By advanced metrics, Jordan’s best seasons were a tiny bit better. He soaked up more possessions as a scorer, and maintained astonishing levels of efficiency at the upper bounds of individual usage rate.

Divide their cumulative advanced numbers by games played — both regular season and playoffs — and Jordan outproduced LeBron on a per-game basis by a small margin. No one burned brighter.

The assist gap is not gargantuan. Jordan dished 5.7 dimes per game in the playoffs, compared to 7.2 for LeBron. Jordan has a small edge in postseason steals, LeBron a smaller one in blocks. The rebounding numbers aren’t close. LeBron is a different weapon on defense — more of a rim deterrent, offering more positional flexibility.

As one executive opined this week: “Jordan was the better isolation scorer, but LeBron is better at everything else.”

Perhaps. That said, isolation scoring is paramount late in big games. And boy would it be a delight to watch prime Jordan — one-time Defensive Player of the Year, an award LeBron has never won — fly around in this era of loosened defensive rules.

The gap in cumulative stats is going to be a chasm. Barring injury, LeBron will be the league’s all-time leading scorer. (It went unnoticed, but in Game 5 against Miami, LeBron passed Karl Malone for No. 2 all time in combined regular season and postseason points.) He could double Jordan in assists and rebounds. LeBron is not hanging on, compiling stats. He’s still the best player. We are still near his peak.

Be careful dismissing LeBron’s 10 Finals appearances as the product of a weak East. During Jordan’s six title runs, the four highest East seeds aside from Chicago posted a .640 combined winning percentage — with an average net-rating of plus-4.8 points per 100 possessions, per ESPN Stats & Information research. The same subset during LeBron’s run to eight straight Finals: a .623 mark with a net-rating of plus-4.5. As our Kevin Pelton has argued, the player pool is deeper now.

LeBron’s ceaselessness must be heard. Jordan did not, or would not, endure this long at the top.

At minimum, it’s a debate now. Jordan backers can no longer shout “6-0” and declare it over. Maybe it’s a matter of taste. Do you prefer peak value or long-term near-peak consistency? How much do you weigh LeBron’s 2011 Finals collapse against Jordan’s perfection?

For some, perfection is all that matters. LeBron could never unseat Jordan. To win one game, their answer will always be Jordan — and in that framing, it’s hard to disagree all that strongly.

But the totality of LeBron’s career is undeniable. If he wins one more title, and has maybe two more seasons almost on par with this one, the grounds for Jordan as the greatest ever — the criteria by which he “wins” the debate — will get precariously narrow. There is a chance, maybe a good one, LeBron drives this GOAT conversation closer to a consensus than anyone would have imagined possible a decade ago.

Inside this grueling, improbable and incredible Lakers title run