NASHVILLE — The parking lot at Nissan Stadium had long since cleared out, but superfan Clay Trainum was in no hurry to leave. Hours earlier, Nashville SC had made its MLS debut, losing to Atlanta United 2-1. The result wasn’t what Trainum wanted, but defeat did little to take the shine off the day. NSC held its own against an Atlanta team that at the time was thought to be one of the league’s powerhouses.

An announced crowd of 59,069 cheered on the home side, a record for a soccer match in the state of Tennessee, and the team’s most vocal supporters stood in the south stand for the entirety of the match. There was a chill in the air, but Trainum was enjoying the final embers of the day, one that for him was years in the making.

“The team did well. The fans did well,” Trainum said. “But this isn’t the end. This is the beginning.”

– MLS announces schedule for remainder of 2020 season

– Stream FC Daily on ESPN+

– Stream out-of-market MLS matches live on ESPN+

It’s staggering how much the hopes and dreams for the team, its fans and the city have been sidetracked since that February night. Nashville has taken its share of hits over the years, from the reservoir collapse of 1912 to the flood of 2010, the latter of which remains a “where were you when …” moment that saw Nashville come together, even as the tragedy gained little in the way of national attention.

But the past five months have delivered body blow after body blow. Less than 48 hours after NSC’s inaugural MLS match, a tornado ripped through the Nashville area, killing at least 24 people and injuring more 200. The COVID-19 pandemic then upended life to an even greater degree. The Metro Nashville Health Department has reported 257 confirmed COVID-19 deaths and more than 27,000 cases.

NSC wasn’t immune. The team was forced to withdraw from the MLS is Back tournament because of a cluster of positive COVID-19 tests among the players. Most poignantly, Nashville SC CEO Ian Ayre lost his mother, Beryl, to the virus in April.

Then there were the nationwide protests surrounding the death of George Floyd, which affected Nashville, and the subsequent protests of the killing of Jacob Blake. Although Nashville played on the day of a player-led walkout on Aug. 26, defender Jalil Anibaba, a founding member of the advocacy group Black Players for Change, has continued to speak out against racial injustice.

“At this point in time, it’s about unity,” Anibaba said the day of the walkout. “We’ll continue to show that through our conversations internally but also through our actions.”

The sport has since returned, with Nashville hosting three matches, albeit without fans. All of this has served to hit a pause button on so much of what NSC was trying to accomplish — namely gaining a toehold in Nashville’s consciousness.

“We had this kind of prizefighter moment, where we felt like every time we stood tall, we got knocked down and had to get up again,” Ayre said. “It’s been not what anyone would have wanted or expected, but I’m a big believer that you learn a lot in the most difficult times.”

In Nashville, the NHL’s Predators have blazed a path for how an expansion team in an unfamiliar sport can get its hooks into a sporting populace in which football — the American kind — remains king. Sellouts at Bridgestone remain the norm for the Preds, but replicating that success will be difficult, especially in a city with much more to it than bachelorette parties and country music.

“There is an energy in and about the city that I don’t think people from outside really notice,” said Newton Dominey, the president of the Roadies, one of the NSC supporters groups. “I think it’s because country music has been the absolute top of the flagpole for so long that people, I guess, just haven’t noticed the other things. We’re a tech city. We’re a healthcare city. It gets a lot more rock and roll than country. And Nashville throws a helluva party. It is a party city. ‘Nash-Vegas’ is real.”

Bringing soccer back to the Music City

In some respects, NSC is emblematic of the challenges facing the city. The breakneck pace of growth has slowed a bit in recent years — but only just. During a five-minute cab ride between downtown hotels, the number of construction cranes dotting the skyline easily runs into double digits, lending credence to the joke that the cranes are Tennessee’s unofficial state bird. Yet not everyone has been able to take part in the city’s growth. Pre-COVID-19, according to a 2018 estimate by the U.S. Census Bureau, the city’s poverty rate was at about 16%.

Odessa Kelly is the executive director of Stand Up Nashville, a coalition of community and labor groups that helped negotiate a community benefits agreement relating to NSC’s stadium project. At Woolworth on Fifth — the epicenter for Nashville’s civil rights movement in the 1960s and where some of the first sit-ins took place — Kelly mused on how the city has grown.

“Development has had the largest positive and negative impact on the city,” she said. “Nashville traditionally has been a blue-collar town where people are willing to work hard and can have a good quality of life here. Now we have so many people who are working full-time jobs or working two or three jobs and can’t afford to live in the city. The people who are making Nashville, they can’t afford to stay in the city that they’re growing.”

Soccer is lauded the world over as the people’s game. Can Nashville SC build bridges between old and new and from community to community?

Initially, Ayre seems like an odd choice to lead that effort, with his Liverpudlian accent making him seem out of place in the American South. But growing up in Liverpool — plus his stint as managing director at Premier League giants Liverpool FC — gave him an up-close perspective on how deep connections can run between team and city. Sure, LFC has a head start of more than 100 years on Nashville SC, but Ayre is determined to try.

Three days before Nashville’s opener in February, Ayre was in a New York City hotel attending the league’s media day. The buildup to Saturday’s match was such that he joked, “I can’t wait for Sunday,” the better to get into the rhythm of the season and find out what kind of team he had.

“It’s almost like building the motor car, and Saturday’s the first time you get to drive it,” he said. “But you gotta keep tuning it and getting better.”

Ayre sees some similarities between his adopted hometown and the Liverpool of his youth. Nashville might be an entertainment city, but selling Nashville SC has meant engaging in all manner of meet-and-greets with potential fans, whether 10 people in a bar or 1,000 at an event. In the process, he has discovered a hardworking ethos largely out of view of the glitzier environs.

“That’s the Nashville way,” he said of the number of meetings he has had. “Look me in the eye. Come and tell me honestly what you’re trying to do and who you want to be and the team wants to be, and come and tell me why I should show up.

“People aren’t impressed with shiny, celebrity status. Nobody gives us a chance because we maybe don’t have the most world-famous coach or player at this point in time, but we have a plan.”

Execution of that plan is in part the responsibility of GM Mike Jacobs. Behind his desk at the team’s temporary offices at Currey Ingram Academy, he has a message written on a white board: “Mitigate Risk.”

“I just want to make sure we’re more educated than everybody else,” he said. “It doesn’t mean we’re not going to take chances, but have them be more educated chances rather than a guessing game.”

That is borne out in the team he has assembled. Much of Nashville’s hopes, at least in the attacking half of the field, rest on German attacking midfielder Hany Mukhtar and Costa Rican winger Randall Leal. Neither is a household name. But combined with MLS veterans such as Dax McCarty and Walker Zimmerman, Jacobs’ hope was to lay a foundation that he can build on.

“I think that kind of makeup of our team appeals to a whole group, different ethnicities, different styles,” he said. “I think for us, on the field we wanted to resemble new Nashville and old Nashville. We wanted to have the entertainment factor of something special with this blue-collar gritty mentality also.”

Six months on, Nashville has found its feet on the field, even amid the forced exit from MLS is Back. NSC finds itself ninth in the Eastern Conference, with a record of 3-5-3. In the generously expanded playoff format in which 10 of 14 teams from the East will qualify, that’s enough to be among the playoff places. But the lack of offensive firepower has been a significant weakness, so much so that Nashville recently signed Benfica forward Jhonder Cadiz on loan.

Will it be enough? For NSC to reach the postseason, it likely will need to be.

2:14

Nashville SC’s David Accam shares his candid thoughts on the boos from FC Dallas fans while both teams knelt last week.

A team built in Nashville

When MLS announced 12 candidates for an expansion franchise in January 2017, Nashville’s odds of securing one of the two slots seemed long. The city soon caught up and could boast the golden triad of fan base, deep-pocketed owners and stadium plan, but it reinforced the impression that Nashville was late to the soccer party. The reality is that Nashville has its own rather tortured soccer history.

Trainum and I met at a bar called The Centennial in The Nations neighborhood. It makes for an apt venue, given the extent to which old and new collide. Amid new buildings that contain cafes and coffee houses, an abandoned grain silo rises with a mural of longtime West Nashville resident Lee Estes. It speaks to how the city’s denizens don’t want the past to disappear too quickly.

Closer to the ground is another, less conspicuous mural. Patrick Swayze’s “Point Break”-era visage adorns an outer wall of The Centennial, where every Aug. 18 they celebrate St. Patrick Swayze’s Day.

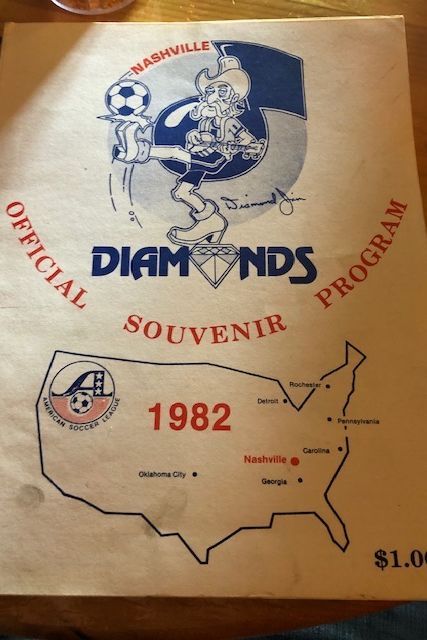

As about 15 West Ham fans celebrate a 3-1 win over Southampton, Trainum — the city’s unofficial soccer historian — and I settle at a table in the back. With the care that one might expect for the original copy of the Declaration of Independence, Trainum cradles the game program from the first match of the Nashville Diamonds, who in 1982 played a solitary season in the American Soccer League. At the time, the NASL had already begun its long, steady descent toward oblivion, and the ASL was suffering as well.

“They won that first game against the Carolina Lightning, they won their last game against Georgia Generals via forfeit, and in between, they went 1-21-4,” Trainum said of the Diamonds. “Yeah, they were real, real bad.”

The Nashville Metros lasted longer, existing in a variety of lower-tier leagues from 1990 until 2012 and spending their final years in the USL’s Premier Development League. That team disappeared with nary a word spoken. “The Metros didn’t even get an obituary because we found out the Metros died when they weren’t on the schedule for the PDL,” Trainum said.

As was the case in many American cities, the sport proved hard to kill off entirely. A Metros fan named Chris Jones — now serving as NSC’s director of fan engagement — started figuring out how a new team could be formed. He decided to form a nonprofit social club that ran a soccer team “because that’s what we were.”

“We just went to Twitter and had zero plan and nothing really other than, ‘The city deserves it,'” he said via telephone. “And people started chiming in, people who I’d never met before. And I figured, let’s all meet up and just kind of talk through it. And the next day, we’re meeting and having discussions of names, colors, all that stuff.”

Jones ended up getting more than 1,000 contributions of $75 each from 26 different countries. The money was put toward operating costs, such as stadium rental and uniforms, and Nashville FC was born. “It was definitely something that was just kind of a passion project, just something to do during coffee breaks and lunch hours, stuffing flat-rate envelopes [of tickets] at midnight,” he said. “My wife’s saying, ‘That better be cleaned up in the morning before we go to school.'”

After merging with another club, Atlas FC, Nashville FC landed in the National Premier Soccer League, and it existed in the de facto fourth tier of soccer for three seasons. The question for NFC then became: How far can we go with this?

It’s a question more fraught than one might suspect. There are soccer fans in the U.S. for whom anything connected to MLS (and its very corporate structure) is to be shunned. No doubt, some fans dropped out along the way, but the NFC members agreed to press on.

“We kind of had this Kumbaya moment that, ‘OK, professional soccer is going to happen here,'” Jones said. “We can either be a part of the conversation, or we can just keep doing what we’re doing, and someone else is gonna make it happen. And so our members said, ‘Let’s pursue it, see what it looks like, what the costs are.'”

That eventually meant a move into the USL and a name change to Nashville SC, with new investors coming on board in the form of Marcus Whitney, David Dill and Chris Redhage. That in turn drew the interest of local businessman John Ingram and later the Wilf family, owners of the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings, who paved the way to MLS.

Underpinning it all was a grassroots community that provided an invaluable foundation.

Soccer Moses

On a damp Monday morning, the man they call “Soccer Moses” can be found at his one-chair barbershop, The Handsomizer. His real name is Stephen Mason; rock fans might recognize him as the guitarist in the band Jars of Clay. Mason readily admits that he’s the living embodiment of another of Nashville’s jokes, that being when you ask someone what they do for a living, they respond, “I’m a musician and …” or “I’m a songwriter and …”

Mason caught the soccer bug when he attended an Arsenal game at Highbury in 1997, but his connection to NSC goes back to the team’s first year in the USL, when his wife, Jude — an English-born devout Watford fan — gave him a season ticket for Christmas. His notoriety has increased in the time since he attended NSC’s opener dressed as Moses, displaying a sign that said, “Let My People Goal.” The inspiration came from JT Daly, the frontman for the band Paper Route, who while in Ireland shouted the phrase in a pub after watching Nigeria’s Victor Moses score against Argentina at the 2018 World Cup.

“I think he probably drank for free the rest of the day,” Mason said.

About three days before the Nashville match, in the middle of cutting someone’s hair, Mason was discussing how he should put the phrase on a shirt. Then he got the idea to dress up as Moses and bring in a banner with the catchphrase instead.

We’ll keep doing our best, Soccer Moses. #EveryoneN

— Nashville SC (@NashvilleSC) March 1, 2020

It wasn’t the first time Mason dressed up for an NSC match, either. He has shown up as a miner, and when October rolled around, he donned a costume that made it look like he was sitting on someone’s shoulders. “Trainum would suggest that while I do like soccer, he thinks I actually like cosplay,” Mason quipped.

Jude chimed in, “It’s not true, but it’s close enough to be funny. I said, ‘You’re gonna go. You’re gonna get on the big screen. Are you sure you want to become the Moses guy? This could stick.'”

She was right. “It’s like ‘Anchorman’ — you know, that escalated quickly,” Mason said. “This might be the Ministry of Soccer Moses.”

The quest for a home

Mason is perfectly positioned to witness the construction of a new soccer cathedral. Across the street from his shop are the Nashville Fairgrounds, site of NSC’s proposed 30,000-seat soccer stadium. The project involves a redevelopment component, a relocated Expo event space, new mixed-use retail and residential buildings, and an upgraded Fairgrounds Speedway capable of hosting NASCAR events. The community benefits agreement negotiated by Stand Up Nashville requires the redevelopment portion to pay a minimum wage of $15.15 an hour and provide affordable housing and daycare for those working on the project.

It was the CBA that helped provide some momentum within the Metro Council, allowing more of the surrounding community to have a stake in the project.

The neighborhood surrounding the stadium site hasn’t really taken part in Nashville’s renaissance. Mason hopes that will begin to change, even though he knows not everyone will want to come along for the ride.

“What’s important for us, I think, as people really passionate about seeing Nashville SC come into its own, is to know that not everybody is going to be excited about some of that,” Mason said. “That growth is going to be difficult for some folks, and I think the Fairgrounds for me represents an opportunity for us to — as best as anyone can right now — partner together and be supportive, be compassionate, be excited and participate because man, there’s so much going on at the Fairgrounds.”

It makes for another clash of old and new Nashville, a divide epitomized by the group Save Our Fairgrounds. SOF has fought the project at every stage and has provided a twist on the pro- versus anti-development argument. The group is led by Duane Dominey (a distant relation of Newton Dominey, head of NSC fan group the Roadies), a former Metro Council member who contends that the building of the stadium violates Nashville’s city charter and that because building a soccer stadium is not among the listed uses of the property, any change must go to a voter referendum.

SOF says its aim is to protect the site’s current uses, such as the State Fair and a monthly flea market, and it fears that if NSC is allowed control over the site’s schedule, other events will be pushed out. SOF has filed a lawsuit to protect those uses.

“I’m not opposed to soccer,” Dominey said. “I’m opposed to soccer at the Fairgrounds.”

Save Our Fairgrounds’ opposition echoes much of what is going on in Miami with the stadium development for David Beckham’s MLS franchise — namely, that public land should not be handed over to private, for-profit interests. There have been accusations that SOF’s motivations have racial overtones, which the group hotly denies. SOF emphasizes that public land is being given away. (NSC is responsible for $13 million in debt service to the city’s sports authority.)

“Is this a land deal or a soccer deal?” asked Rick Williams, another of the group’s leaders. The much-lauded CBA is derided as “unenforceable” and a way of giving Metro Councilmembers political cover. SOF’s plan is to keep the project tied up in the courts for years. The suit went to trial earlier this month.

Ayre dismisses the litigation as “a bit like background noise.” Demolition has gone ahead, and NSC doesn’t anticipate that the lawsuit will impact the project, with the stadium scheduled to open in May 2022. The club’s supporters are clear about what side of the old versus new divide they stand on.

“They’re in the way,” Newton Dominey, the Roadies president, said of SOF. “And instead of trying to be partners, they’re obstacles.”

An opening day success … now what?

About two hours before kickoff of the team’s inaugural match in February, the east parking lot at Nissan Stadium is a hive of activity. Newton Dominey has sold about 50 Roadies memberships in the past hour. Ingram, NSC’s majority owner, is floating and speaks about how “gratifying” the day is.

That joy and optimism have trickled down to the fans, though not all. “I think, at least in terms of marketing and accessing a lot of communities, especially working-class communities, I think the club has failed to do that in a lot of ways,” Scott Kopfler says. “I think there are people that love soccer and that want to be a part of what’s going on and almost aren’t kind of shown the right way by the club.”

Some inroads have been made, however. “La Brigada de Oro” (“The Golden Brigade”), one of the club’s supporters groups that caters to Latinx fans, is putting on a show in the form of dancers in Aztec dress. “We’ve been waiting for this game for the longest time already, so we’re so excited to see all these people right here with us,” says Gabby Acosta, who founded the group with her husband, Abel.

“Cheer for the same team. Cheer for the same passion that we have with the football. This is us, and we hope we can see more people come to every game.”

When asked if the club has done enough with outreach to minority communities, she hesitates. She lauds the effort of Newton Dominey and the Roadies, who helped get the group up and running, but believes that NSC can do more.

“Our people sometimes feel like, ‘OK, this is futbol, but they see — and I’m sorry to say it this way — they see more Caucasian people than Hispanic people, so they feel like, ‘OK, well, you know what? This is not us,'” she says. “We need to bring something else. So that’s why we started up La Brigada de Oro. And this is what we have already.”

That day, Acosta and her fellow NSC fans were more than ready, despite the result. What they couldn’t have anticipated was just how long they would have to wait for the party atmosphere to return, as the hiatus has proven long indeed. Although fans of MLS teams such as FC Dallas, Sporting Kansas City and Orlando City have been able to attend games — albeit with much reduced capacity — Nashville’s fans haven’t.

The end is now in sight. On Thursday, Nashville Mayor John Cooper and the NFL’s Tennessee Titans announced that a limited number of fans could begin attending Titans games starting Oct. 4. The expectation is that once MLS’s schedule is ironed out, NSC will soon be able to follow suit, though that news has come too late for some, at least for this season. Newton Dominey and Trainum said they have opted out of attending more games in 2020, applying their season-ticket money to the 2021 campaign instead. Not even the possibility of a playoff game will sway them. The atmosphere just wouldn’t be the same, they say.

“I’ve waited six months,” Trainum said. “I can wait a few more.”

Mason is of similar mind, though he hasn’t completely decided. One thing that is certain is that Soccer Moses won’t be making an appearance under the current conditions.

“It’s a case of the ‘Already’ and ‘Not yet,'” Mason said. “There’s still the longing of what we tasted and what’s to come.”