Football — college and the NFL — is wrestling with how to play amid the coronavirus. A look into the pages of history reveals some of the same questions surrounding travel restrictions and the desire to play just over a century ago.

The H1N1 virus — called the Spanish flu when it broke out in 1918 — is estimated to have infected 500 million people worldwide, with 675,000 deaths in the United States, according to information from the CDC.

Longtime Pro Football Hall of Fame historian Joe Horrigan and curator and historian at the College Football Hall of Fame Jeremy Swick have spent time over the past several months looking back at football during the 1918 flu pandemic.

“Something that struck me right away, that the circumstances, a time of social unrest, a health emergency like most had never seen and people trying to navigate all of that,” Horrigan, 68, said. “You see there is a sense of people wanting, really wanting, to try to get back to normal and that sports, even in those early days of pro football, pro football was going to try to have a role in that.”

Horrigan, who retired in June 2019 after 42 years with the Pro Football Hall of Fame, is considered the leading professional football historian. He says the impact of the Spanish flu on sports included a list of cancellations and schedule changes, such as the Cubs and Red Sox ending an abbreviated baseball season by playing the World Series in September 1918, a series that featured a young left-handed pitcher named Babe Ruth for the Red Sox. Players, coaches and umpires wore masks during the games.

Pro football in 1918 — the NFL wasn’t formally organized until 1920 — was largely a regional affair in the Midwest’s Rust Belt, with an irregular quilt of locally organized teams. Most of those teams elected not to play or were prevented from playing by local guidelines as men were being pulled into the military for World War I, as well as the effects of the pandemic. There also were travel restrictions and limitations on crowds.

There were just a few professional teams that played limited schedules, including in the Ohio League, which included what would be one of the NFL’s original teams: the Dayton Triangles, who won the title in the abbreviated 1918 season.

But if you’re looking for a record of professional football in 1918, the Hall of Fame lists no 1918 entry in its historical timeline.

“You just see the difficulty teams were having because of the difficulties the communities they were in were having,” Horrigan said.

College football was king at that time but many schools did not play in 1918, while others elected to play a limited schedule of three or four games. Because of the restrictions, few games were played until late October or early November.

“A lot of teams that were able to play, were able to play because perhaps many of their players had not yet shipped out — World War I was a relatively short war for those in the United States when compared to, say, World War II, so the cycle of men leaving and returning was different,” Swick said. “There were a lot of travel restrictions in place, however, for the war and the virus, so it became a local affair.”

1:24

Louis Riddick applauds Dont’a Hightower and other players for opting out of the NFL season instead of putting others at risk.

ESPN senior writer Ivan Maisel, whose personal library includes about 300 books on college football, said information about the 1918 season is hard to come by.

“You see a lot of the information, the war and the pandemic are treated largely as one thing in the discussion about college football,” Maisel said. “And the fact is they were. They were very separate things, but you also see the pandemic isn’t really talked about in much detail. But the differences in who played, how many games they played, how the season looked for each school, I think that’s something we could see in the season to come.”

The Army-Navy game was not played in 1918, for example, and the Missouri Valley Conference, which included Missouri, Nebraska and Kansas at the time, canceled its conference season. LSU did not play football in 1918 and later honored it’s now-named “silent season” a century later in 2018 with a commemorative uniform.

Knute Rockne, in his first year as Notre Dame coach, saw his team’s travel restricted because of the flu outbreak and the war. The Fighting Irish finished the season 3-1-2. At one point, Notre Dame played a game — against Wabash — that had been scheduled the same day.

But President Woodrow Wilson, who later cited a need to improve “morale” in the country, ordered football teams to be created at military posts around the nation and those teams played some of college football’s powers in 1918.

John Heisman’s Georgia Tech team played almost a full schedule — it went 6-1 that season. Tech surpassed 100 points three times, with six games at their home field, including games against the Georgia Eleventh Cavalry and Camp Gordon, a camp built in Georgia for World War I that was closed in 1920.

“The NCAA did exist then, so there were guidelines for schools to follow to play, but I’m certain nobody was checking IDs on all of the players from those military teams,” Swick said. “It’s certainly possible there may have been some older players, players who might have been the age of those on professional teams at that time. There were likely a variety of players in some of those games.”

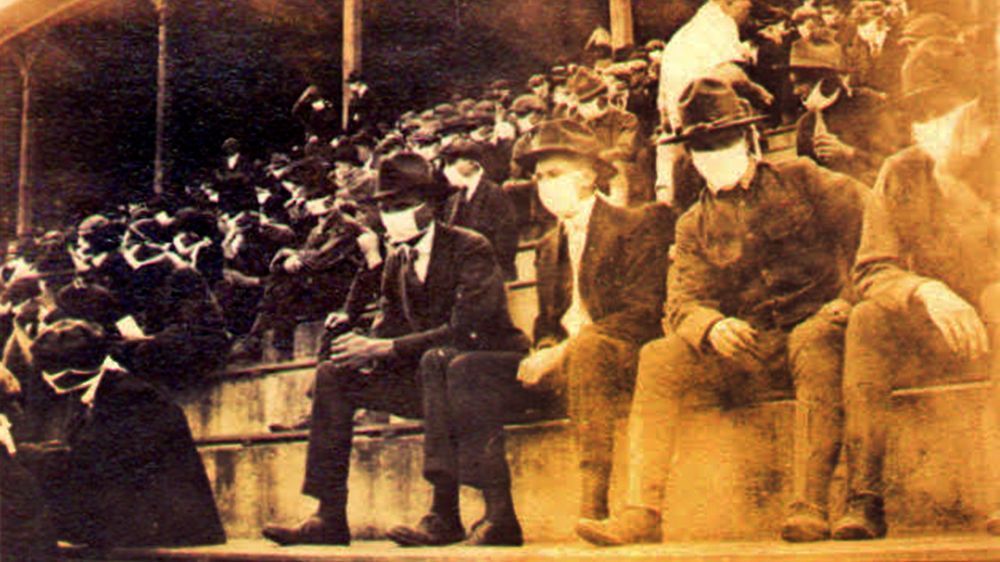

A photograph that has resurfaced plenty in recent months — taken by a Tech student during the 1918 season — shows fans at a game wearing masks.

The only away game Georgia Tech played that year was Nov. 23 at Pitt, which was coached by Glenn “Pop” Warner. Pitt won 32-0 and reports from the time list a crowd of about 30,000 at Forbes Field. That win had many declare Pitt as the national champion.

“I would say, in looking back at it, you see the teams that succeeded were simply more fortunate,” Swick said. “It’s a virus, it didn’t pick and choose then and know who was coaching the team or how organized you were or how much talent you had or if more of your players had simply not shipped out to war yet. It was far more of a roll-of-a-dice thing about who won and lost.”

Pro football took the uncertainty of the schedule, travel and scarcity of players as a sign it needed to be better organized.

“And in looking back, you see a sense of the pandemic, as World War I was ending, having somewhat of role in everything that was happening in the country, having a role to push people to organize in pro football,” Horrigan said. “That the need for organization for teams, for players, could clearly be seen by those trying to make pro football a reality as they tried to navigate everything that was going on … and in 1920, just two years later, the NFL is born.”

Swick said he has found references to some college campuses “using correspondence to hold classes,” so students were not allowed on campuses for part of the 1918 school year.

“It’s hard to tell fully what it was like because the culture sometimes wasn’t to save things,” Swick said. “Some things are lost in someone’s attic right now or have been thrown into a dump long ago, but you see places where the students weren’t on campus, but there were attempts to have school so that impacted the ability for some to play sports, including college football, beyond simply having many able-bodied males fighting a war.”

To get a sense of life and the reach of pro football in those pre-NFL years, Horrigan has mined newspaper clippings to see how people grappled with the desire to return to games and gatherings as the virus was active.

A notice about school closures in an October 1918 issue of the Lansing (Mich.) State Journal said teachers were trying to find the best way to limit their contact with students as “some of them have declined to go into homes where there are serious cases in influenza and pneumonia fearing they might contract the disease.”

A notice in the Ransom (Kan.) Record in December 1918 offered “considerable pressure has been brought to persuade the health board to remove the ban from public gatherings, in view of the approaching holiday season that the people may indulge in Christmas-tree festivities and other social entertainments” and that people would be allowed to return to some gatherings if there wasn’t a “serious turn in the course of the prevailing pandemic scourge.”

Said Horrigan: “Those are the kinds of cities, especially in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Michigan, in that part of the country, where pro football is operating. And while large public gatherings were banned at times and the football season, college and pro, was largely canceled, you do see these attempts to play. And in looking at it, you really have to believe that with the aftermath of war, of the pandemic, those events put people in a position to try to reorganize things, and the NFL is one of the things that came out of that.”