July 2012, and Bradley Wiggins emerges over the crest of a hill with one of his domestiques in Peyragudes in the French Pyrenees – a first Tour de France victory for a Briton all but assured.

It was the beginning of his planets aligning so spectacularly he would end the summer dripping in Olympic gold and heading for a knighthood.

Perhaps cruelly, the domestiques, who shelter the lead rider to save his energy as they hike through the mountains, are always ignored – even if they are there physically at the finish, they just peel off the road and head for the ice bath alone.

Except this domestique was getting bored and twitchy as they headed towards the line, gesticulating to a rapidly fading Wiggins to hurry up as the race leader started to melt in yellow.

Christopher Froome was his name – a sort of a wirey, less expressive version of Wiggins, without the sideburns.

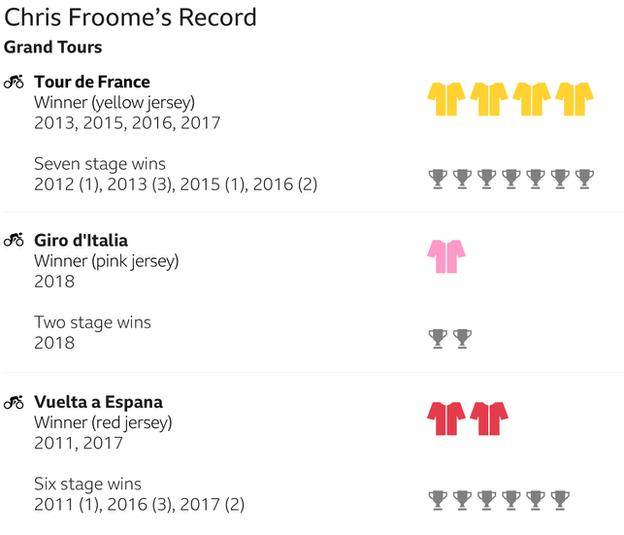

A decade and seven Grand Tour career victories (all for Team Sky) later, Froome has his own story to tell – a story that might lack the style of the mod who went up a mountain and came down a knight, but which has the substance of a classic, overcoming-the-odds tale.

He might look and sound a bit like an up-to-date version of snooker’s ‘Mr Interesting’, Steve Davis, but he possesses the flair of football legend Diego Maradona, the ruthlessness of Formula 1 great Michael Schumacher and the tenacity of tennis star Rafael Nadal in that lanky frame.

It’s why his departure from Team Ineos – formerly Team Sky – after they decided not to renew is contract feels like the end of era.

Early promise

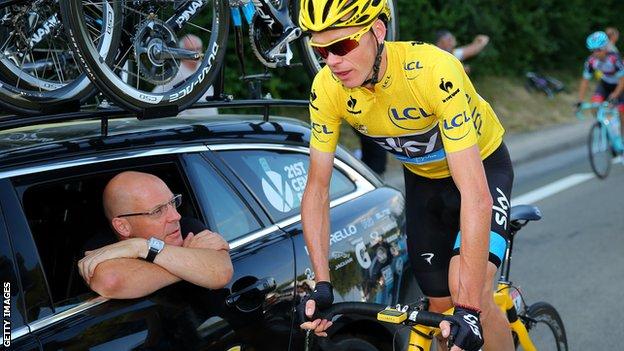

No-one knows the glittering story of British Cycling better than Sir Dave Brailsford, who led riders to so many gold medals across three Olympic Games, and who then took on his life’s ambition – to win the Tour de France with Team Sky.

He signed Froome for this new team, but he was not simply plucked from the golden generation being bred at Manchester’s velodrome in the early noughties.

“I was in a team managers’ meeting [at the 2006 Road World Championships in Austria], and he walked in, rain-sodden, representing himself,” says Brailsford.

Across the room stood a gangly, awkward 21-year-old lad from Kenya, who had travelled to Austria alone to compete in a time trial – only after he ‘borrowed’ a laptop from the guy who looked after Kenyan cycling and entered himself into the race without telling him.

No-one even noticed him, let alone gave him a chance – until he walked into the same room as Brailsford that day in Salzburg. Froome subsequently crashed three seconds into his time trial, hitting a race delegate when hesitating at a fork in the road.

“For somebody with the background he had, he caught our eye. That told us a lot about the tenacity of the guy, and the desire. There’s a character in there,” adds Brailsford.

Crash Froome’s unlikely background

Ah yes, that background. On the face of it, a white, privileged, boarding school educated man from Africa could breeze protected into the sanitised, optimised world of elite sport, couldn’t he?

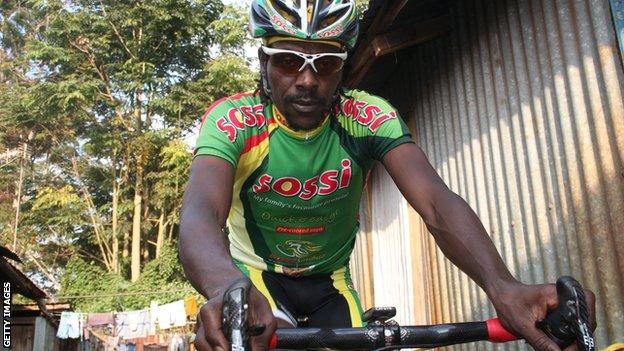

As a form of escapism from a family imploding and parents heading for divorce, Froome would ride for as long as the Kenyan countryside would take him.

He was a young man who was largely alone but who spent much of his time riding with a cycling club formed in the Nairobi slums.

Eventually, after an adolescence spent doing 5am time trials for fun and drafting lorries down motorways to get home more quickly, he began to earn his own form of privilege.

That’s why Brailsford saw the one thing any budding cyclist or endurance athlete needs to get a look-in: a good engine, the heart and lungs.

Whether born with it, or developed during mile after mile in the Kenyan sun, Froome can put out a massive amount of power through the sheer speed and the high cadence of his pedalling.

“My technique was terrible,” said Froome during his time on the rise. “I gained the nickname ‘Crash Froome’.”

By his own admission, it’s still not a great technique – arms stuck outwards like a cartoon character, head bobbing around. You can easily spot him nestled in the kaleidoscope of the peloton.

Never, ever give up

To win three-week Grand Tour races you need to be fast and able to climb mountains, which are almost opposing skills.

Several of the greats – Miguel Indurain, for example – are unbeatable time trialists who hang on in the mountains, or vice versa. But when he’s on top form, Froome can win a speed contest or a hike up to a mountain summit by a country mile.

Awe-inspiring as his physical, combative style can be to watch, it’s the moments of raw tenacity which endure.

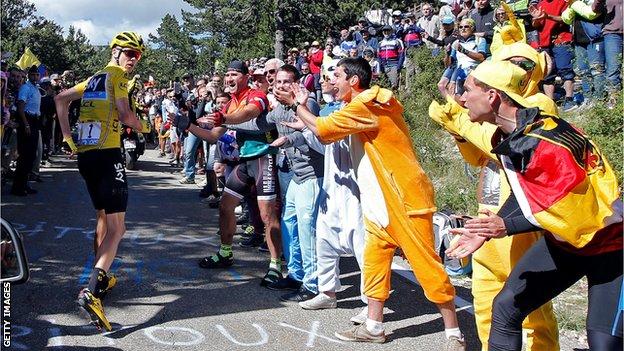

On the way to his second Tour win in 2015, Froome had a pint of urine thrown into his face. Hard to take for any of us, but how about when you are at the very nadir of your physical suffering and being hunted down by your fiercest rivals who are pleading with the gods for you to fail?

Tour win number three in 2016 wasn’t any easier. In fact, it was comical. Late into stage 12 he was found by TV cameras jogging without a bicycle up a path to the iconic Mont Ventoux. Surrounded by jubilant fans, Froome had crashed into a motorbike so severely his own bike was unrideable and the road was too remote for him to be reached with a replacement for several minutes.

Then there’s the moment he clawed back a usually unassailable three-minute-and-22-second deficit in one incredible mountain climb on the Jafferau to win the 2018 Giro d’Italia – mouths of everyone in the sport agape of how much power he was able to put through his pedals, and for so long. The raid even included avoiding another crashed motorbike, this time in a dark Alpine tunnel.

And do we include last year’s horrific, life-threatening crash in a Tour warm-up race, in which he sustained the kind of injuries that would have ended most riders’ careers? Yes, we do.

It’s also worth mentioning that “adverse analytical finding” he was eventually cleared of in 2019 for using asthma medication – purely because it opened up a debate to the wider public around legal drug use in a sport where the athletes induce their own asthmatic conditions through sheer effort and overuse of their respiratory systems.

But the wider world is still learning to trust again after what could have been a century of doping in cycling, and still learning what it is like for athletes such as Froome – who spend six hours a day on a bike pushing their bodies that little bit harder every time to get it in peak condition.

A legacy in full swing

Froome isn’t going anywhere away from the sport. We will still see those arms at almost 90 degrees, sawing away at the climbs in September.

But there will be a vacuum without his presence at Team Ineos, and things are already different now.

Ineos are a world-beating cycling outfit whose primary modus operandi is to be the best and get results in a global sport. They have to pick the world’s best riders, not the best Britons.

Colombia’s 23-year-old superstar Egan Bernal will try to retain his Tour title for Ineos this year, as some of the older, chiefly British, guard of that early Sky/Ineos set-up reach the twilight of their careers.

But back in 2009, when Froome joined Sky, it all seemed so unlikely. He wasn’t fashionable, he just wanted to compete in a European sport suffering from a drugs overdose and a serious bout of elitism.

He also had to fit into the philosophy of a team based in Manchester made up of people who ‘didn’t know about that kind of cycling’, representing a country that had forgotten how to ride.

But he did it. And so did we. We are riding again – many of us inspired by Froome himself.

Even Wiggins, history’s poster boy, would acknowledge that.