This week, I’m going to check in with progress reports for quarterbacks from the 2018 NFL draft. Five quarterbacks were drafted in the first round that year, and I’ll take detailed looks at Lamar Jackson (Tuesday), Josh Allen (Wednesday), Baker Mayfield (Thursday) and Sam Darnold (Friday). Sorry, Josh Rosen; I’ll get to you another time.

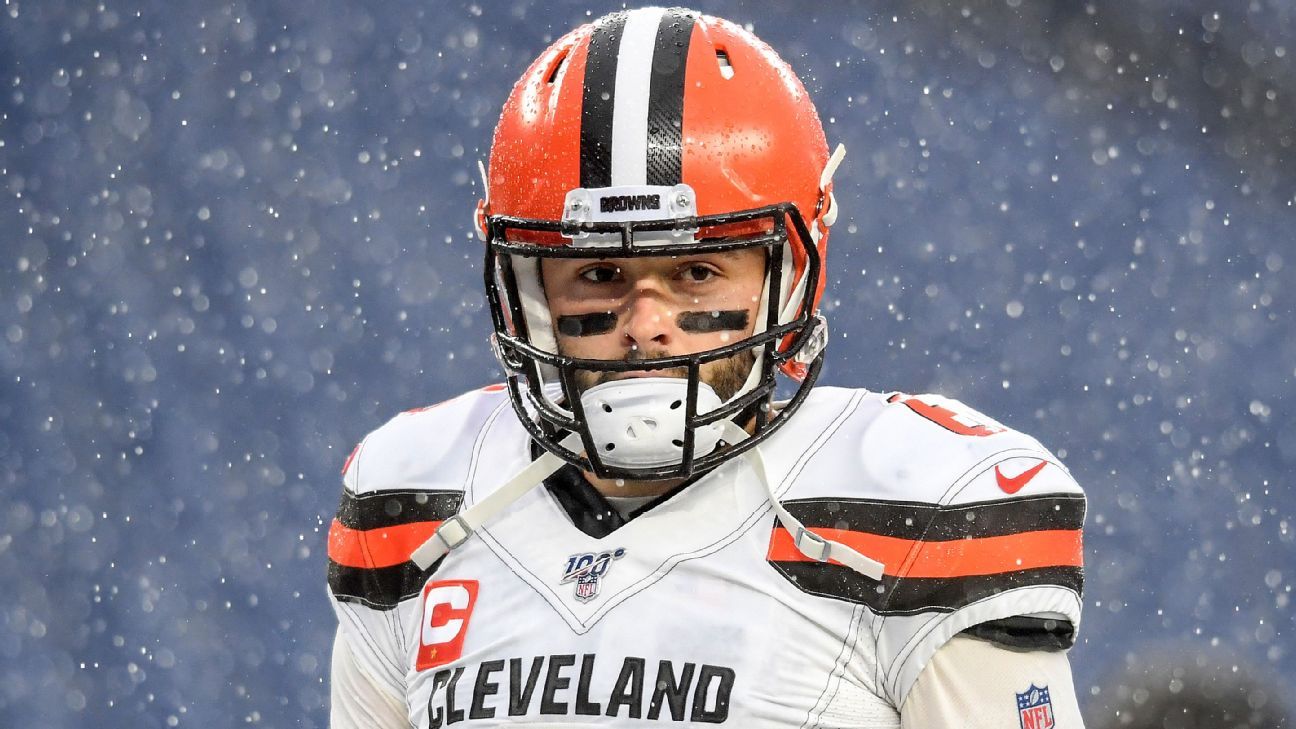

You could argue that no player and team came into the 2019 season with more hype behind them than Baker Mayfield and his Cleveland Browns. I wasn’t on this particular bandwagon, but you could understand why people were excited by the league’s most notoriously snakebit franchise. The Browns had finished 2018 by winning five of their last seven games, with Mayfield posting the league’s fourth-best passer rating (108.4) in the process. A developing offensive line had allowed opposing teams to sack Mayfield just three times over that stretch, and with general manager John Dorsey trading for Odell Beckham Jr. over the offseason, Freddie Kitchens’ team seemed to be set to make their first playoff appearance since 2002.

Well, you know what happened. The Browns went 6-10. Beckham wasn’t healthy. The offensive line was a mess. Dorsey and Kitchens were both fired. The qualities that seemed like pluses for Mayfield in 2018 became liabilities in 2019. His confidence spurred belief in a previously moribund franchise as a rookie, but then he spent the offseason taking shots at teammates and fellow quarterbacks. Confidence seemed to turn to cockiness. The plays he made off schedule in 2018 turned into structureless hero ball in 2019. Mayfield was unflappable in 2018 and spent chunks of 2019 tilting at windmills.

Let’s evaluate what went wrong for Mayfield during a wildly disappointing 2019 campaign. With the Browns replacing Kitchens with former Vikings offensive coordinator Kevin Stefanski, I’ll also get into how the new scheme could help Mayfield and what he needs to do to qualify as a success in a crucial campaign.

Jump to a section:

How did Mayfield take a step back?

Where he needs to improve most

Can a new staff fix his issues?

Three ways to measure success

Where it all went wrong for Mayfield in 2019

There are several bewildering plays that could qualify as the season-in-a-nutshell for the Browns. The first snap that came to mind from Mayfield’s season as I prepared for this progress report, though, came all the way back in September. It was Cleveland’s final offensive snap in Week 3, with the offense facing a fourth-and-goal from the 4-yard line down 20-13 to the Rams with 33 seconds left. This was a high-profile game for the Browns against the defending NFC champions in their first prime-time game on a Sunday or Monday since 2015. Here’s what happened (animation courtesy of NFL Next Gen Stats):

Mayfield had exhibited a habit during the first three weeks of bailing to his right under pressure, either imagined or real. L.A. pass-rusher Clay Matthews undoubtedly noticed. Once overmatched left tackle Greg Robinson was beaten at the snap by Dante Fowler Jr., Mayfield started to bail out of the pocket. Instead of rushing to try to get to where Mayfield was, Matthews barely engaged with right tackle Justin McCray and instead traveled to where Mayfield was going. The subsequent pressure from Matthews forced Mayfield into a desperate throw off his back foot, and while he actually gave receiver Damion Ratley a chance to catch the ball, the throw was intercepted by safety John Johnson III to end the game. Even if the line had managed to protect Mayfield, no one was remotely open. On one of the most important plays of their season, the Browns had absolutely no hope of succeeding.

There wasn’t one single reason the Browns’ offense fell off in 2019. There were plays in which the offensive line gave Mayfield little chance of executing the concept. There were times in which he had time to throw and simply missed his receiver. There were moments in which the highly touted receiving corps didn’t do its quarterback any favors. Kitchens’ playcalling didn’t often put his weapons in a place where they could succeed.

In many cases, these problems coalesced and interacted with each other on the same play or within the same concept. Take the Browns’ screen game. With players like Beckham, Jarvis Landry, Nick Chubb and Kareem Hunt, they should have had one of the league’s most dynamic screen games. A successful screen game would have kept some of the pressure off Mayfield and Cleveland’s struggling tackle combination of Robinson and Chris Hubbard. Instead, at least once per game, I saw screens like this:

This is not quite as cool – screen to the TE where three blockers go into the flat and the only one who touches a 49ers player goes for a ride pic.twitter.com/7fvJqIVsav

— Bill Barnwell (@billbarnwell) June 27, 2020

This is a slip screen to tight end Demetrius Harris, the sort of call that should work great against a team like the 49ers, who have an active pass rush and mostly play zone coverage. Harris gets pushed too far wide by his chip attempt, and while the Browns actually have four blockers in the flat for him against three defenders, none of them actually has the angle to make a successful block. The only guy who comes close to blocking a defender is center JC Tretter, who gets sidestepped like a bull and goes tumbling to the ground.

Cleveland games were full of screens in which something would go slightly wrong and it would blow up the play. The offensive line wouldn’t toe the line between holding up pass-rushers and letting them through, either forcing too much quick pressure on Mayfield or leaving the receiver stranded against defenders. Linemen and blocking receivers would seemingly fall asleep and end up a step or two late to make their blocks. Mayfield would try to complete screens that were horribly blown up before he even decided to release the pass. I’ve never seen an offense in which the receiver was drawing dead to the nearest defender before he even caught the screen more frequently than the 2019 Browns.

Having a middling screen game is one thing, but that sort of sloppiness permeated the Cleveland passing attack throughout the season. The line struggled badly with twists and defensive line games. Some of that is talent, but those problems also owe to a line that simply isn’t communicating well. There were too many snaps in which it seemed like the receivers weren’t breaking off their routes at the expected depth or making the sight adjustments to their routes Mayfield was expecting. His pocket presence was erratic; it didn’t seem like the former first overall pick trusted his line, and I can’t blame him.

I’m often skeptical of broad narratives surrounding a failing coach. (I saw the Giants supposedly quit on Tom Coughlin seemingly annually during a run where they won two Super Bowls in five seasons.) It might be too simplistic to suggest that Kitchens was overmatched in his first (and likely only) season as a head coach, but there’s plenty of evidence to support that hypothesis.

The offense didn’t play to the strengths of its weapons. Beckham catching slants from Eli Manning with the Giants became a meme, but Kitchens couldn’t unlock the same sort of production on Beckham’s signature route. According to ESPN’s route classifications using NFL’s Next Gen Stats data, no receiver who ran 30 or more slants produced fewer expected points each time they ran a slant than Beckham.

Kitchens tagged some of Cleveland’s run plays with the ability to throw a smoke route to Beckham, but perhaps owing to his injury, he couldn’t do much on those throws. Even when you remove screens from the equation, OBJ averaged 3.2 yards after catch in his first season in Cleveland, his worst mark as a pro and a far cry from the guy who was north of 5 yards after catch in 2015 and 2016.

At times, it felt like Kitchens would lean on run-pass options (RPOs) as a way to try to create easy completions for Mayfield. The problem was that every defense Cleveland played knew those RPOs were coming, and while the Browns would have some success, there was rarely a Plan B for when the defense sniffed them out. Take the Steelers, for example, who gave them what appeared to be the look they wanted to throw a stick route off of RPO, only to drop T.J. Watt off the line into Mayfield’s throwing lane and get pressure with a two-man pass rush:

The problems with the offense were never resolved. There was a three-week span in which Mayfield and his team seemed to right the ship by winning three straight games, including victories over the Bills and Steelers. Mayfield posted an 82.9 QBR over that span, which was the second-best mark in the league behind Lamar Jackson. It seemed like the Browns might right the ship, but they lost four of their final five games, with Mayfield posting a QBR of 51.9 and completing just over 57% of his passes.

There were moments where it looked like Mayfield and the Browns could live up to the hype, if for a play or two. Kitchens would pull out something innovative, like a shovel pass into an option with Landry and Beckham. When they were able to protect Mayfield, we occasionally saw the big plays we would have expected from his link with Beckham. Chubb finished 37th in Football Outsiders’ version of Success Rate, but he overcame the blocking issues to produce a bunch of big plays, most memorably the 88-yard touchdown that sealed Cleveland’s win over Baltimore.

Those moments were few and far between. The additions Cleveland made this offseason were less about creating those moments of magic and more toward building the stability the offense lacked a year ago. The Browns already had their magicians; they spent this offseason going after the players who would save them from having to throw away one or two plays each series thanks to a whiff on a blocking assignment or sloppy execution. Let’s see what they’ll have to do to get Mayfield back on a superstar trajectory.

Where Mayfield needs to improve

By just about every measure, Mayfield was a below-average quarterback last season. Let’s start with the broadest measures. Of the 26 passers who threw at least 400 passes, he ranked 25th in passer rating, ahead of only Andy Dalton. He was also 25th in completion percentage (where he topped Josh Allen) and interception rate (Jameis Winston). While Mayfield’s accuracy was his calling card coming out of college and through his first pro campaign, he wasn’t on point there in 2019. According to NFL Next Gen Stats, his completion percentage of 59.4% was 3.5% below expectation, which ranked just ahead of Allen and 22nd in the NFL.

Advanced metrics were a little more optimistic. Mayfield ranked 19th in DVOA and 16th in Total QBR, with the latter figure finding some subtle value in his performance. His sack rate was around league-average, but he was often sacked in relatively low-value situations, so he was hurt less frequently by sacks than most other passers. He added 14 first downs via pass interference penalties, which was tied for the second-most in football behind Philip Rivers. He also didn’t run frequently, but he was efficient when he did, ranking seventh in DVOA. He averaged 6 yards per rush attempt and moved the chains 15 times across 24 tries.

If we have to start somewhere in fixing Mayfield, begin with his pocket presence. It was clear from September on that he didn’t trust his offensive line or believe that he was going to be able to work through his progressions from a stable pocket. He was too quick to bail laterally to escape the pocket when he didn’t see what he wanted or expected at the end of his dropback. At the first hint of pressure, he often tried to escape. Once he did, things typically didn’t go well. He posted a passer rating of just 44.9 when he threw from out of the pocket in 2019, the second-worst mark in football. He was at an even 100.0 during the 2018 campaign. Also, nobody held onto the ball longer outside the pocket on average than Mayfield, a sign that he wasn’t finding productive solutions to his problems once he escaped.

What makes this even more frustrating is that Mayfield came out of Oklahoma as someone who had grown dramatically as a pocket passer dealing with pressure. He spent his three years as a starter under Lincoln Riley, who focused many of his drills on training him to keep his eyes up and make plays in the pocket under pressure. One such drill included peppering him with medicine balls while he moved within the pocket, forcing him to keep his eyes upright and protect the football while waiting to find an open receiver.

Mayfield’s QBR under pressure at Oklahoma jumped from 9.1 in 2015 to 36.2 over the 2016 and 2017 campaigns; the only quarterback in the nation with a better QBR under pressure over those last two seasons was Sam Darnold. Mayfield wasn’t awful under pressure last season — his 18.4 QBR was 12th — but there were too many times in which he left the pocket and missed an opportunity because he wasn’t comfortable or confident working there.

The biggest way the Browns aim to remedy Mayfield’s shakiness is to improve their protection. Robinson was out of the league before being arrested for allegedly possessing 157 pounds of marijuana, while Hubbard was moved into the same swing tackle role he excelled with as a member of the Steelers. The Browns spent lavishly on their replacements, signing Titans right tackle Jack Conklin to a three-year, $42 million deal in free agency before using the 10th overall pick on Alabama tackle Jedrick Wills Jr.

One of the reasons Hubbard excelled in Pittsburgh before struggling in Cleveland was the presence of offensive line coach Mike Munchak, who molded Hubbard from an undrafted free agent into a valuable, versatile offensive lineman. Munchak is now with the Broncos, and one of the few offensive line coaches who have a case for being in Munchak’s league joined the Browns this offseason. It’s one of the most valuable under-the-radar additions any team made.

1:55

Domonique Foxworth and Damien Woody give their expectations for Baker Mayfield and the Browns this season.

Bill Callahan has built very good lines wherever he has gone over the past decade, often by molding young players into valuable contributors. With the Jets, it was D’Brickashaw Ferguson and Nick Mangold, both of whom turned into regular Pro Bowlers after Callahan arrived. In Dallas, Callahan inherited Tyron Smith and then helped Travis Frederick turn into one of the league’s best centers. With Washington, Callahan molded Brandon Scherff into a top guard and got the most out of players like Morgan Moses, Chase Roullier and Ty Nsekhe. There are a lot of first-round picks in that bunch, but if Callahan can continue to produce stars, the Browns are going to be in much better shape up front.

Better protection will help Mayfield, but that’s not going to be enough. New offensive coordinator Alex Van Pelt has already taken on the task of trying to rebuild Mayfield’s footwork, suggesting that Van Pelt, whom you might remember during his time with the Bills from 1994 to 2003, wants his quarterbacks’ footwork to be “…like Mozart, not Metallica.” Teaching a quarterback new footwork isn’t easy under normal circumstances; with the coronavirus eliminating minicamps, Van Pelt has used a video application he learned about from a golf lesson to help Mayfield study remotely.

If Mayfield grows more comfortable with the footwork Van Pelt is prescribing, the benefits could be significant. He would get into his dropback and presumably get the ball out quicker, which will help keep pressure away. It could also reduce the number of small steps he takes at the end of his drop to try to help create throwing lanes, which would make it easier for his tackles to pass block.

The problem is that mechanical changes don’t always stick. Blake Bortles spent 2014 and 2015 rebuilding his mechanics, but many of those mechanical fixes went by the wayside during a difficult 2016 campaign. Bortles then rebuilt his mechanics in 2017 before losing the plot again in 2018. Will Mayfield trust in the new footwork when he needs to make a big play? If he’s feeling pressured and the results aren’t there, will he revert to his old footwork? We won’t know until we actually see him on the field this season.

Concise, repeatable footwork also plays a huge role in quarterback accuracy, and a more accurate Mayfield should be able to improve on his 21-interception total from 2019. After adjusting for era, his 3.9% interception rate was the second-worst mark since the merger for a quarterback in his second season over 400 or more attempts. Only Vinny Testaverde’s 35-interception campaign from 1988 was worse.

The bright side, if there is one, is that Mayfield was the unluckiest quarterback in the league when it came to interceptions. Football Outsiders tracks interceptions and near-interceptions and found that he had 23 adjusted interceptions after you account for things like Hail Mary attempts or passes that were tipped into a defender’s hands by a drop. Those 23 picks would typically turn into 17.7 real interceptions; instead, Mayfield threw 21. The resulting 3.3-interception difference was the most for any quarterback.

Mayfield might have had the two most infuriating interceptions of the season, and you could argue each was unlucky. One was, to my recollection, the only time an NFL defense has intercepted what’s known as a tap pass or touch pass, courtesy of the 2019 Patriots defense. The other was the sixth most-unlikely interception of the year by Next Gen Stats’ completion expectation, when Antonio Callaway dropped a sure touchdown and somehow kicked it to a 49ers defender for a goal-line interception:

oh no pic.twitter.com/fQjhOsLO3k

— Bill Barnwell (@billbarnwell) June 27, 2020

Even if you want to take away most of the blame from Mayfield for that interception, he needs to make better decisions and more accurate throws in 2020. In watching those interceptions, while several of them went off of his receiver’s fingertips, they also weren’t well-placed. He often seemed on different pages with his receivers, expecting them to settle when they would continue to run or vice versa. Defensive backs suggested they knew what was coming. More than anything, though, he made bad decisions in trying to make throws he couldn’t hit.

The biggest move the Browns made to rebuild Mayfield after a shaky season was to hire Stefanski, who was a finalist for the job when it went to Kitchens last offseason. Stefanski spent only one full season as the offensive coordinator and playcaller for Minnesota, but the results were impressive; the Vikings improved to 10th in offensive DVOA, while quarterback Kirk Cousins had his best season as a pro in the process. In many ways, Cousins was great in the places where Mayfield struggled.

Can Stefanski fix Mayfield?

Cousins was one of the most accurate quarterbacks in football last season. While Mayfield’s completion percentage above expectation (CPOE) was among the worst in the league, Cousins’ 69.1% completion rate was 5.5 percentage points above expectation, the best mark in the league for a passer with 400 attempts or more. He was fourth in the NFL in adjusted completion percentage at 74.6%. The same Cousins who posted historically bad interception rates early in his career threw picks on just 1.4% of his throws in 2019, the ninth-lowest rate in the league.

The only other time Cousins has approached his 2019 level of play was in 2016, when his offensive coordinator in Washington was a little-known 30-year-old named Sean McVay. Browns fans understandably would love it if the 38-year-old Stefanski turned into the Midwestern version of the Rams’ coach, but it’s not quite that simple. Let’s dig into the offensive structure and scheme Stefanski used in Minnesota last season and see what it might do for Mayfield.

To start, the Vikings ran the ball. A lot. On early downs while games were still competitive, the Vikings had the NFL’s fifth-highest run rate. With Gary Kubiak on staff as a consultant, Stefanski installed a version of the Shanahan/Kubiak rushing attack that has unlocked huge seasons from a small army of running backs. Unsurprisingly, Dalvin Cook had his best pro season, although the Vikings still only finished 16th in rushing efficiency.

Unsurprisingly, the passing attack Stefanski implemented to work off that running game featured heavy doses of play-action. More than 31% of Cousins’ pass attempts incorporated play-action, the fourth-highest rate of any starting quarterback. The tactic worked: Cousins posted the second-best passer rating in the league off play-action, a whopping 130.1. He was still effective without play-action, ranking sixth in passer rating without a play fake, but his passer rating there was more than 33 points lower.

As I mentioned in the Josh Allen piece on Wednesday, a heavier dose of play-action will make Mayfield better, in part because it makes everyone better. The splits for quarterbacks using play-action last year were staggering. When quarterbacks didn’t use a play-fake, they posted a passer rating similar to that of Philip Rivers. When they did use play-action, quarterbacks posted a passer rating closer to that of Patrick Mahomes. Why shouldn’t NFL teams take advantage of that opportunity every chance they get?

It wasn’t a huge surprise that the Vikings went with a heavy dose of play-action. Before the season, Cousins reported that Minnesota’s analytics department showed him how much more effective he was as a play-action passer. Stefanski admitted to reading the various studies on play-action circulating around the internet, including Ben Baldwin’s article suggesting that there’s no relationship between “establishing the run” and play-action efficiency.

With the Dorsey regime removed from power after the disastrous 2019 campaign and analytics-friendly executive Andrew Berry taking over as general manager, the Browns are again one of the league’s most numbers-friendly organizations. Mayfield was a totally different quarterback when he used play-action a year ago; his 106.2 passer rating with play-action was the 13th-best mark in football, but that fell all the way to 68.7 without using play fakes, which ranked 32nd. Mayfield’s interception rate jumped from 2.5% with play-action to 3.8% without. Research suggests that NFL teams haven’t yet hit a point where defenses stop reacting to play-action.

In a vacuum, everything seems to point to the Browns posting one of the highest play-action rates in league history. My lone concern goes back to Mayfield and where he wants to work from. In 2019, 135 of Cousins’ 139 play-action attempts came from under center. Mayfield typically isn’t under center that frequently. Nearly 82% of his pass attempts came out of the pistol or shotgun a year ago, and while that number was closer to 50-50 when play-action was involved, I wonder whether Stefanski & Co. will want to put Mayfield under center that much.

It also seems likely that the Browns will change their personnel packages. Last year, they worked out of 11 personnel (one running back, one tight end, three wide receivers) more than 56% of the time. It was their least effective package; by NFL Next Gen Stats’ version of Success Rate, the Browns were successful on only 43% of their snaps out of 11 personnel. Cleveland was far more effective out of 12 personnel (50% Success Rate), which they used about half as frequently. They were even more successful in limited doses of 20 personnel (53% Success Rate) and 21 personnel (58%).

The Vikings were in 11 personnel just 20.6% of the time last season; they essentially used five personnel groupings, and the other four all included at least two running backs or two tight ends. Like the Vikings, the Browns have two star wide receivers and a dynamic running back. It’s not an accident that they went out this offseason and signed Falcons tight end Austin Hooper, retained former first-rounder David Njoku and traded for Broncos fullback Andy Janovich. Even without considering that Landry is recovering from hip surgery and might not be ready to start the season, it’s clear that the Browns are going to move away from using 11 personnel as their base offensive package.

What they have that the Vikings didn’t, though, is Hunt. Alexander Mattison looked promising as a rookie, but Hunt’s skill set — particularly as a receiver — makes him an interesting proposition for this offense. Mayfield’s best numbers as a passer last season came when he had Hunt on the field, either alongside Chubb or on his own. His passer rating was north of 59 in both situations. He really struggled in his 118 dropbacks without one of his two starting backs on the field, posting a scarcely believable QBR of just 18.0.

There are two places Hunt can make a significant impact. One is in the screen game. The Vikings were one of the most efficient screen teams in the league a year ago; Cousins converted 44% of his screens into first downs, the highest rate for any starting quarterback. The other is when the Browns empty out the backfield and try to match up Hunt against a linebacker. Mayfield posted the league’s 31st-best passer rating (70.8) out of an empty sets a year ago, and while Cousins wasn’t much better at 79.9, the Vikings didn’t frequently use empty looks.

With Hunt and Hooper, the Browns have the weapons to come out in 12 or 21 personnel, spread the defense out wide with motion and rebuild Mayfield’s confidence in the quick game by giving him easy mismatches to exploit. They preferred to use RPOs as their quick game for Mayfield in 2019; I expect them to revert to a more traditional approach this season.

How to measure success from Mayfield in 2020

OK. Having laid out all of that, what would qualify as a successful return to form for Mayfield?

1. He needs to grow more comfortable in the pocket. He can’t panic as frequently as he did in 2019. His footwork needs to be quieter. I don’t think he is ever going to be a prototypical dropback quarterback, which is fine, but the rhythm and timing of the offense fell apart last season. The tackle additions should help, but at the end of the day, Mayfield is the one who is supposed to overcome the weaknesses around him.

2. He needs to cut his interception rate. It’s almost impossible to succeed in the modern NFL with an interception rate approaching 4%. Mayfield’s accuracy and decision-making has to improve. Some of the interceptions weren’t on the quarterback, but he can’t put so many passes in positions where it’s easy for receivers to tip them into the air. Again, his footwork is going to be key.

1:50

Anita Marks predicts if the Browns will win over or under their projected 8.5 wins next season.

3. He needs to leave no doubt. This is a critical year for Mayfield. It’s not out of the question that this could be his last season as the Browns’ starter if he continues to struggle. It seems crazy to imagine him going from toast of the town as a rookie to fighting for his job in Year 4, but the Bears went from thinking Mitchell Trubisky was a franchise quarterback after the 2018 season to turning down his fifth-year option a year later. The Browns will have to decide on Mayfield’s fifth-year option next spring, and if he disappoints for the second straight campaign, it’s not going to be an easy call.

Last year, while he struggled and took plenty of criticism, it was easy to make excuses and point toward the problems elsewhere on the roster. The coach wasn’t up to the task. His tackles were awful. His receivers were hurt or injured. Now, the excuses are (mostly) gone. If Mayfield doesn’t look like the quarterback we saw in the second half of 2018, the blame is going to be squarely on his shoulders. The Browns don’t have to be great, but they can’t be depressing, at least not on his account.