FOR JULIUS JONES, H Unit has been home for 18 years.

He’s on death row, serving time for a crime he maintains he didn’t commit, in a cell alongside 53 others stacked in two rows inside the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester.

In 2002, Jones was convicted of first-degree murder for the death of Paul Howell. The 45-year-old businessman was shot in the head on July 28, 1999, while sitting in a tan GMC Suburban in his parents’ driveway in Edmond, Oklahoma. Two shell casings were found at the scene. Howell’s sister, Megan Tobey, was the only eyewitness.

After a three-day search for a suspect described as a young black male wearing a white shirt, a skull or stocking cap, and a red banana over his face, Jones, then 19, was arrested.

“As God is my witness, I was not involved in any way in the crimes that led to Howell being shot and killed,” Jones said in his clemency report. “I have spent the past 20 years on death row for a crime I did not commit, did not witness and was not at.”

In October 2019, Jones filed his clemency report, asking for his sentence to be commuted to time served. Jones has now exhausted every appeal and is eligible for an execution date, which could be as soon as this fall.

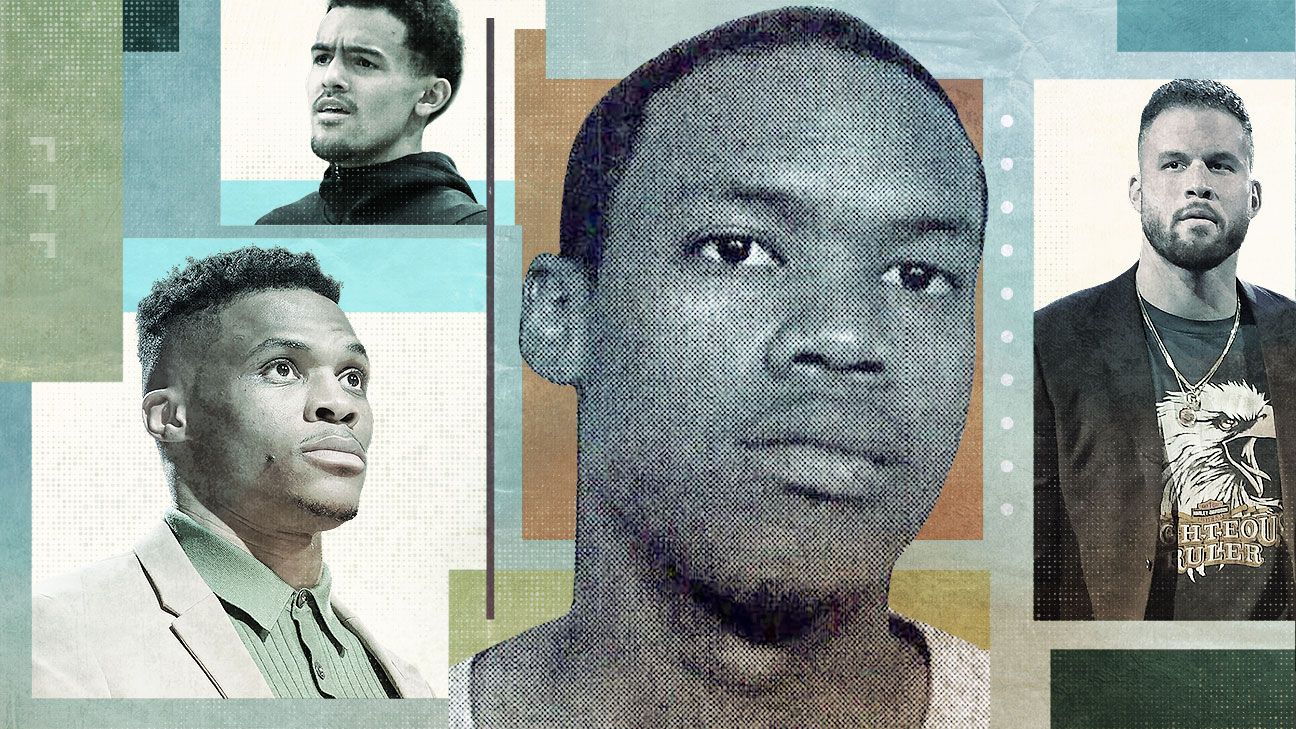

The Julius Jones Coalition, a group established in 2019 composed of family, friends and community organizers pursuing Jones’ innocence, has gathered support in recent months as NBA stars Blake Griffin, Russell Westbrook, Trae Young and Buddy Hield and NFL quarterback Baker Mayfield authored and sent letters to the governor’s office.

Each letter hit a key issue that led to Jones’ conviction — racial bias, a flawed investigation, an ill-equipped defense — and points to the wrong person sitting on death row.

“[Jones’] conviction was tainted by a deeply flawed process,” Westbrook, the longtime face of the Oklahoma City Thunder who is now with the Houston Rockets, wrote in his letter. “As more details come to light regarding his situation, I join with many voices to express sadness and profound concern regarding his conviction and death sentence.”

The name recognition of the athletes — all of whom have strong ties to Oklahoma — is something organizers hope will resonate, especially in the present moment. As protests against police brutality across the United States persist, Oklahoma City’s Black Lives Matter chapter has included a commutation for Jones in a list of demands presented to Oklahoma City Mayor David Holt.

For those fighting for Jones’ freedom, the goal has remained straightforward: draw as much attention to his case as possible, show the Pardon and Parole Board there’s a reason to consider his clemency and get it to the governor for approval.

“I never realized the impact people could have in making sure justice is truly served. I’m willing to do anything.”

Blake Griffin

The momentum behind Jones’ case wouldn’t have been possible without the state’s mishandling of two executions in 2014 and 2015. Following scathing reports that led to resignations and a full review of the prison’s procedures, all executions in Oklahoma were put on hold, keeping Jones from receiving an execution date.

But the state announced in February that it plans to resume executions this year. Jones’ legal team said when it does, he will likely be one of the first in line.

A couple hundred feet from Jones’ prison cell is the death chamber, remodeled since its last use. It replaced a version from the 1950s that was the site of 111 executions.

On the other side of a door leading into the chemical chamber of the execution room is the operations area, and as part of the renovations, three cream-colored phones were added.

One is labeled “external extension,” the line out of the prison. Another is “internal extension,” which is a line into the execution room to let the warden know it’s time to begin.

And on the right, under a label in a black frame, hangs the last phone: Governor’s office.

MORE: WNBA star Maya Moore’s extraordinary quest for justice

THE GRIFFIN BROTHERS were staples inside the gym of John Marshall High School in Oklahoma City. Both Blake and Taylor watched in awe as their father, Tommy Griffin, paced the sidelines as the Bears’ varsity basketball coach.

“That was like my prime years of just being obsessed with basketball, begging my dad to go to every practice,” said Blake Griffin, who is now with the Detroit Pistons. “We’d go to all the home games and some of the away games. The guys on my dad’s teams were like my heroes at the time.”

Jones, a combo guard 10 years older than Blake, was one of the future All-Star’s favorite players.

“He played with a certain charisma, a certain swagger, that was very smooth,” Blake said. “Those are the guys that always stood out to me, the guys that made the game look easy.”

“We looked up to him,” Taylor Griffin said of Jones. “He was one of my dad’s players that we talked to and joked around with.”

Tommy Griffin remembers Jones as a tenacious defender, a good teammate and a leader. Jones was part of an undefeated state championship team as a sophomore, then became a role player as a junior and eventually a full-time starter as a senior.

“He was always doing his job, all the teachers liked him, he was very well liked by the players on the team,” Tommy said. “He was just a good person to have around.”

Tommy is Oklahoma coaching royalty, with eight state championships scattered across stops at three schools, including coaching his sons at Oklahoma Christian School.

Tommy said not just anybody could play for him. He was demanding, pulling no punches when it came to discipline and fundamentals — two areas of strength for Jones.

“[Jones] always found the open man. He was a great passer,” said Jimmy Lawson, Jones’ high school teammate and best friend, now a community organizer who has been fighting on Jones’ behalf since Jones’ murder conviction.

Lawson met Jones in the sixth grade, and they played basketball together through high school. Lawson went to Grambling State to play basketball, but despite offers from a few small colleges, including some to play football, Jones wanted to go to the University of Oklahoma.

He was an excellent student and had an academic scholarship to OU in the College of Engineering. After his freshman year, he planned to walk on and join coach Kelvin Sampson’s basketball team in the fall of 1999. Tommy was ready to vouch for him.

“I would’ve jumped right on that as quick as possible,” Tommy said.

But he never got the chance. Jones was arrested that summer. Tommy was watching the news when he saw his former player’s face on TV. He thought it had to be a different Julius Jones.

“It couldn’t be the Julius we know,” Tommy remembered thinking. “He had never, ever shown any type of characteristics or traits like that.”

Tommy was involved in the original trial as part of the character witness list but did not testify. After Jones’ conviction, Tommy lost track of the case over the years. His sons didn’t have a full understanding of the details until watching the 2018 docuseries, “The Last Defense,” which highlighted issues surrounding Jones’ trial.

“I watched that and was kind of in shock like everybody else,” Blake said.

After the documentary aired, Blake called his dad. He wanted to help. It came by way of Kim Kardashian West, reality star turned criminal justice reform advocate.

To start, Kardashian West told Griffin to write a letter to Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt and the Pardon and Parole Board in support of Jones’ clemency petition.

“I don’t pretend to know the ins and the outs of the justice system,” Blake Griffin said. “I just know the story, and I know that it’d be a true tragedy and shame for another innocent person to not only be jailed, but put to death.”

Kardashian West and her team have played a significant role in the letter-writing campaign, as has Scott Budnick, producer of the 2019 legal drama “Just Mercy,” along with local PR firms, all using connections to collect influential voices.

It wasn’t just the letters from Kardashian West, Griffin, Young, Mayfield, Hield and Westbrook. It was a letter from Bryan Stevenson, author of “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption,” his memoir on which the film is based. It was letters from faith leaders, politicians, professors and lawyers.

Blake Griffin and other players’ voices may carry weight with the public in Oklahoma, but legal analysts caution celebrity causes don’t always generate much of a reaction from judges and elected officials.

“Crowd-think has always played its role in shaping culture for both the good and the not-so-good,” former Oklahoma County District Attorney Wes Lane said. “The challenge for the Pardon and Parole Board or the Governor — in any case before them — is discerning what the right thing to do is, regardless of what seems popular.”

But what all the players can’t ignore is the role race may have played in both the trial and sentencing.

“You’re not given a fair chance, you’re not given a fair shake at life in that trial,” Blake Griffin said. “Let alone just life in general growing up a minority in a predominantly white state. I hate to say that if he was white it would be different, but there’s a chance.”

BEFORE JONES’ ARREST, police searched his family’s home. Siding was torn off. Windows were shattered. Blinds were ripped down. Rooms were ransacked. Clothes were pulled from closets and drawers. Mattresses were cut and flipped. Picture frames were smashed.

“It wasn’t just, ‘We’re doing our job,'” Jones’ brother, Antonio, said in the documentary. “They were sending a message. It was hate.”

Jones was arrested the next morning and transported to the Edmond Police Department, but before the pass-off, arresting officer Detective Tony Fike stopped on 122nd and Western Avenue and told Jones to get out. Jones noted in his clemency report that Fike took his handcuffs off and said, “Run n—–, I dare you, run.”

“I stood frozen,” Jones said in the report, “knowing that if I moved, I would be shot and killed.”

The Edmond Police Department denied the allegation.

“To hear that a juror allegedly used the N-word when referring to Julius during trial, yet remained on the jury, is deeply disturbing to me.”

Russell Westbrook, in his letter Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt

In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected reviewing a claim of a racist juror being involved in Jones’ trial. The alleged remarks surfaced in 2017, when another juror, Victoria Armstrong, sent a Facebook message to Jones’ legal team claiming juror Jerry Brown said, before evidence was presented, that the trial was a “waste of time” and they should “just take the n—– out and shoot him behind the jail.”

“I was tried by a jury that included at least one racist,” Jones said in his clemency report. “And I never had a chance.”

Armstrong said she went to the judge with the information the following day during the trial.

“Beyond the obvious shortcomings of the trial, another issue that continues to weigh on me is the obvious racial bias that permeated Julius’ arrest, prosecution, and conviction,” Mayfield, former Oklahoma and current Cleveland Browns quarterback, wrote in his letter.

“Every American is supposed to be guaranteed a fair and impartial trial,” he continued. “But when your arresting officer calls you the ‘N-word,’ when a juror calls you the ‘N-word’ and when all of this unfolds in the context of decades of death penalty convictions slanted against black men, it is impossible to conclude that Julius received fair and impartial treatment.”

The trial record does not include a racial slur. At the time, the judge asked the jury that included only one black member to reaffirm their ability to remain impartial, and the trial continued.

“To hear that a juror allegedly used the N-word when referring to Julius during trial, yet remained on the jury,” Westbrook’s letter said, “is deeply disturbing to me.”

CHRIS “WESTSIDE” JORDAN was a high school teammate of Jones at John Marshall, and the two remained acquaintances after graduation.

Initially, Jordan told detectives he stayed at Jones’ house the night after the murder, but at trial, he changed his story to say he never did. The Jones family said in the documentary that Jordan stayed in the upstairs bedroom, while Julius slept on the downstairs couch.

Three days after the murder, through tips and informants, police zeroed in on Jones and Jordan as suspects. The day police searched the Jones’ home, Jordan sat in the back of a squad car. Investigators came out with a gun, wrapped in a red bandana that was found in a second-story crawl space.

Jordan told detectives he saw Howell get shot and drop to the ground, and that he might have touched and might have even loaded the murder weapon. But during the trial his story evolved. Jordan testified that he was 300 feet away, never saw the gun and only heard a gunshot.

“Julius’ co-defendant, who testified against him, changed his story no fewer than six times when interviewed by the police,” Young, an All-Star guard with the Atlanta Hawks, wrote in his letter. “Julius’s attorneys, who lacked death penalty experience and were woefully unprepared, failed to cross-examine the co-defendant regarding his inconsistencies.”

Jordan’s testimony was uneven enough for the interrogating detectives to ask him in one session, according to the transcripts, “We don’t have this backwards, do we?”

Jordan pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and was sentenced to life with possibility of parole after 30 years.

At the time, police didn’t test the red bandana for DNA. Jones’ post-conviction team pushed for it to be tested, but the results didn’t help its case: A forensics lab in Virginia found Jones’ DNA on the bandana.

“Those defending the murderer have disseminated misinformation and lies regarding the trial and evidence in this case. We have never been afraid of the truth,” Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater said after the results were announced in 2018. “The light of these results pierce the dark lies.”

After Jones was convicted, Jordan bragged in Oklahoma County Jail that he was the real gunman who killed Howell, according to signed affidavits from two inmates. One, Manuel Littlejohn, was on death row. The other was serving life without parole. Neither was given anything in exchange for the information.

Littlejohn said Jordan claimed “Julius didn’t do it” and “Julius wasn’t there,” boasting he had wrapped the gun in a bandana and hid it in the attic of the Joneses’ home. Jordan also allegedly revealed he was getting out after only 15 years, not the minimum of 30.

“[Jones’ attorneys] did not mention that Julius’ co-defendant had bragged to fellow inmates that he had committed the homicide, not Julius,” Young wrote.

In 2007, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals determined neither witness would have been reliable and denied Jones any relief.

Jordan was released from prison in 2014, without parole. He served 15 years.

THE DESCRIPTION TOBEY gave police of the person who killed her brother was specific: a young black man wearing a white shirt, a red bandana and a black skull or stocking cap. But there was one other piece of information. She said the gunman had a piece of hair sticking out from the cap, half an inch to maybe an inch.

Nine days before Howell was killed, Jones was stopped for reckless driving in a separate incident. Though there were no charges filed, police took a booking photo. It showed Jones with short, cropped hair. Jordan, however, consistently wore his hair in cornrows.

At trial, Howell’s sister was cross-examined and asked if she was sure about the hair description. She said she was.

The jury never saw the photo of Jones.

“Julius’ public defenders lacked the resources, expertise and motivation to fight for his life,” Westbrook wrote in his letter. “His legal team failed to present a photo of Julius taken nine days before the crime which would have dramatically contradicted the eyewitness description.”

JONES WAS HOME for the summer, living with his parents after completing his freshman year at OU.

His family was adamant Jones was eating spaghetti and playing Monopoly with his siblings at the time Howell was murdered 20 miles away on July 28.

“Julius was sentenced to death in a trial rife with error and failure, putting into question the reliability of his conviction,” Blake Griffin wrote. “I am very concerned that his original attorneys did not present an adequate defense for Julius. The jury did not hear that the Jones family was hosting a game night at the time of the crime and that Julius was present.”

Jones was assigned two public defenders at trial, David McKenzie and Robin Bruno, and after reviewing details of the family’s story, the lawyers didn’t believe the alibi would hold up against cross examination.

On the sixth day of the trial, the state rested its case and the defense had time to present theirs. McKenzie stood up and said, “the defense rests.”

They called no witnesses.

TWO YEARS AGO, Cece Jones-Davis — no relation to Julius — watched the documentary and felt compelled to get involved. So she helped build out the Julius Jones Coalition and began gathering signatures for the petition on the Justice For Julius Jones website.

A little more than a month ago, the petition had around 230,000 signatures, an encouraging number for Jones-Davis. She hoped for six figures when she started the petition, and when it hit 150,000 last December, she thought they were “cooking with grease.”

Even as the number of signatures plateaued in April, Jones-Davis and her team believed it could make a difference.

Then the letters were released. Today, Jones’ petition has 5.7 million signatures.

“It’s a demonstration of the power and the will of the people,” Jones-Davis said. “It shows there are people paying attention. There are people who equally feel burdened by this and that people hope that Oklahoma takes this seriously.”

For years, the Jones family was working behind the scenes telling Julius’ story but found little support. They tried to get the Innocence Project involved, but the Oklahoma chapter doesn’t handle death row cases. The docuseries was the beginning of a movement, and it has crescendoed at this moment with a renewed national focus on criminal justice and racial inequality.

“This is it. We’ve got the momentum,” Lawson said. “I think more people are aware about it, and with the current environment and a focus on social injustice, it’s inspired it even more.

“Everybody is screaming justice now, so to have a case like this in the midst of it is working to our favor, if you will.”

James Ridley of Devoted Media and @jimmylawson25, Julius’ best friend and fierce advocate, teamed up at the OKC #blacklivesmatter protest to support the movement and to lift up #JusticeforJulius pic.twitter.com/nvT24zU7uY

— Justice for Julius (@justice4julius) June 12, 2020

Jones has only a tangential understanding of the star power of Westbrook, Griffin, Young, Hield and Mayfield. But he knows now how much their voices carry.

“[Jones] was extremely honored. And grateful,” Lawson said. “Very grateful to understand that players of their magnitude are on his side and fighting for his freedom. He couldn’t be more pleased. That’s just huge.”

How much the signatures and letters will impact the Pardon and Parole Board, or possibly, Governor Stitt, remains to be seen. But Stitt has been a strong voice in the arena of criminal justice reform, commuting 450 sentences last November alone. Since 1981, 10 Oklahoma death row inmates have been exonerated.

“To have someone of that magnitude like Blake Griffin to say, ‘Here’s my voice, I’m fighting for Julius as well,’ and then of course the Oklahoma City legend himself, Russell Westbrook, to dive in is big time,” Lawson said. “Then to have Trae Young [speak on] Julius’ behalf — to have those three names is a huge blessing.

“With those three guys stepping up, it’s probably going to inspire some of the others to take a look and say, ‘You know what, we’re in this time of this social injustice movement … now’s the time.'”

For the Griffins, the letter campaign isn’t the final push. Blake is willing to fly to Oklahoma, to meet people face-to-face, to further make the case for Jones.

“I never realized the impact people could have in making sure justice is truly served,” Blake Griffin said. “I’m willing to do anything.”

Those fighting for Julius Jones’ freedom now hope the governor heeds their call.