Editor’s note: This story contains graphic descriptions of domestic violence.

HIS VOICE IS calm. “I need to show you something,” he says.

It’s 5:31 p.m. on Tuesday, Nov. 23, 2010, at 1203 Foxtree Trail, a stucco ranch in the sleepy suburban neighborhood of Apopka, Florida, when James Martin takes a 9-inch Buck knife and plunges it into his wife’s torso.

At first, Christy Salters Martin, world champion boxer and the only woman boxer ever featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated, doesn’t know she’s been stabbed. The blade’s that sharp. The jab’s that quick. She’d been sitting on the edge of the bed, fighting off a migraine, lacing up her sneakers in preparation for a run.

Martin had gotten one shoe on before her husband strolled into the room, his face frozen, his hips shifting in a coy dance that obscured whatever he’d hidden behind his back.

I need to show you something.

Police reports indicate, after the first stab, Jim thrusts the knife in again, and again, three times down Martin’s side until a fourth puncture rips into her left breast. Stunned, Martin rears back, tumbling on the bed, kicking at Jim. He slices at her leg, dragging the knife along her calf muscle. Eight inches of flesh detached from the bone, flapping onto her ankle, dangling by a thread of skin.

At some point in the frenzy, Jim slashes his own palm on the blade and drops the weapon. Seeing an opening to get away, Martin tries to heave herself off the mattress but stumbles, falling at the foot of the bed, where the pair wrestle until Jim pins her and begins beating Martin’s head into the floor and on a nearby dresser. Martin’s ear snags, nearly ripping off. It’s then, as Jim hovers over her, his fingers gripping and yanking her hair, that Martin feels the weight of the gun in the pocket of her husband’s denim shorts.

She immediately recognizes the 9 mm Taurus as hers, a pink pistol she usually kept stuffed between the mattresses. As Martin paws at the firearm, desperately trying to wrangle it free, the clip falls out, thudding on the carpet. Jim then takes the butt of the gun and slaps it across Martin’s jaw.

Stabbed, beaten and broken, Martin looks her husband in the eye, cries out, “Motherf—er, you cannot kill me.”

At that, Jim rises, stands over the body of his wife of 20 years and fires the pistol, discharging the single chambered bullet into her chest, 3 inches from her heart.

As Martin bleeds out, Jim hastily wipes down the knife with a T-shirt. He places the pink gun beside his wife’s body. She hears her lung gurgling, feels the wet of her blood seep into her clothes. She pleads for him to call 911.

Jim walks away, returns to the room holding an unplugged landline phone, pretends to punch the buttons.

“I can’t get it to work,” he says. “I wonder why?”

And so it goes for nearly 30 minutes until Martin’s pleas quiet. Her breath shallows. Her eyes roll to the ceiling, fixing on the air conditioning vent. Martin prays to God as her husband, satisfied he has killed her, walks to the bathroom and turns on the shower.

Martin can’t recall exactly how long she lay on the bedroom floor, only that when she heard the water running she knew instantly it was her last chance to escape. She opened her eyes, swiveled her body to look for her husband’s shadow reflected in the bathroom tile. When she didn’t see it, she felt sure he’d gotten into the shower. It was now or never.

Martin stood up, dragged her lacerated leg across the floor and limped out the front door, down the winding driveway, past the palms and oaks swathed with Spanish moss. She brought the pink gun with her, evidence, and ran into the middle of the street, flagging down an approaching car, blood dripping from her clothes, one shoe on.

When the driver stopped and lowered the window, Martin tossed the gun into his front seat and begged him, “Please don’t let me die.” The stranger took one look at her condition, nodded for Martin to get in. As she clambered into the back, he dialed 911.

“Hurry,” Martin beseeched. “I don’t want him to know I got out of the house.”

What Martin didn’t realize as she was driven to the Apopka emergency room was that her husband had emerged from the shower. According to court documents, he’d washed, colored his hair, donned his jewelry, a pair of boxer shorts. He was exiting the bathroom in search of a clean shirt when he discovered that the woman he believed he’d murdered was gone.

Frantic, Jim ran out to the driveway wearing only his underwear, just as the car Martin was fleeing in sped away and disappeared down the street.

TEN YEARS AFTER she got in the car that brought her to safety, Martin is halfway through her cocktail when she’s called from the bar to her table at her favorite steakhouse in Austin, Texas. The dining room on that warm January evening is empty, but Martin doesn’t mind. She’s eating early-bird style, her preference, she jokes, because she’s “old and tired, 52 in June.”

The waiter drapes a napkin on her lap solicitously, teases her about her order. Martin teases back, a bit they’ve done before.

Over a surf and turf dinner, talk turns to her beloved sport of boxing and the current female contenders. Martin thinks Katie Taylor is “pretty good.” She admires Amanda Serrano from New York, Laila Ali, who retired in 2007.

“I give Laila credit because she could have just lived her life, like, ‘My dad’s Muhammad Ali!’ but she put the work in.”

Martin values nothing as much as putting in the work. Her own cumulative efforts resulted, last December, in her being among the first class of women elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame. (She was set to be inducted this week, but the coronavirus pandemic forced postponement of the ceremony until 2021.)

“I’m much smarter than people give me credit for as a fighter,” Martin says, pushing a piece of steak around her plate. Her eyes flicker as she adds with a chuckle, “As a person, maybe not.”

Martin says that she often forgot to pick up her check after a fight. For her, it was never about the money.

“When people left, I wanted them to say, ‘Wow, that was a good fight!’ Not ‘That was a good woman’s fight,'” she says. “I didn’t want to be a good woman fighter. I wanted to be the best.”

Before she was the most famous face of women’s boxing, a welterweight champion with a 49-7-3 record and 31 knockouts, Christy Salters was a daughter of Itmann, West Virginia, the firstborn of Joyce and Johnny Salters — Joyce, a stay-at-home mother, and Johnny, a welder at the coal mine. Both of Martin’s grandfathers had black lung. Her younger brother, Randy, also found employment (and suffered grave injuries) in the mines. Martin’s extended family, like so many in factory towns, lived within a mile of one another, kitty-corner or down the block. The whole family swallowed their share of hardship and hard luck, but it isn’t as if they ever expected any different.

Appalachia makes turtles of its people — you grow to the confines of your cage, drag cumbersome hard shells around. If you happen to be reared, as Martin was, in the forlorn heart of rural West Virginia, flanked by dense hollers, inhaling air thick with the dust and fume of an industry indifferent to your survival, you know your worth with firm certainty. Which is to say, not much.

“We’re just a plain family,” Joyce explains. “We don’t like to put on airs, we just like to be plain and happy.”

“Itmann was a coal camp,” Martin says. “A tiny little speck of a nothing town. Mountains and hills and everyone you knew, they’re either miners or railroaders or teachers. I love West Virginia, I love the people there. But I never for one day thought I was going to stay.”

Not that one can ever actually leave Appalachia. Folks from there are like trees at the sea, roots deep, limbs gnarled from ceaseless struggle against winds they can’t control. West Virginia embeds in your soul, prickly and too stubborn to ignore, even if you hightail it to New York City or Vegas or Florida and pretend you never knew what it felt like to walk barefoot over root-strewn alleys.

On the day Martin was born, her daddy made sure nobody besides her mother held her until he arrived home from the mine. The first time he cradled her, he was in his work clothes. Their father-daughter bond would only grow, as Martin became Daddy’s girl, sitting tight by his side at the dinner table (a chair that remains empty when she’s not there). He nicknamed her “Sis.”

“Johnny, whatever he did, Sis was right there with him,” remembers Joyce. This included following her father up dangerous construction scaffolding when she was only 5 years old. “You know, some men don’t want to be bothered with their kids. Johnny isn’t like that. If she had a temperature, he thought he was supposed to rock her, not me. She’s just been his baby from day one.”

“My dad always told me, ‘You can do anything you want to do, be anything you want to be,'” Martin remembers.

What Martin wanted to be was an athlete. As a young girl, she played Little League baseball, rec football, the only girl on both teams. Martin liked basketball most, but — topping out at 5-foot-4½ — she had something to prove, on and off the court.

“I had some schoolyard fights,” she recalls. “I was an aggressive kid.”

“Christy got her quick temper from me,” says Joyce, laughing a little. “We were always close when she was growing up.”

Martin competed on the boys’ basketball team from fourth through seventh grades. When she finally found a girls league, she performed so well it would win Martin a scholarship to Concord University, an hour away from her hometown.

“She talked about being a coach,” Joyce says. “We never thought she’d end up being a boxer. She did have this Smurfette poster in her room that said ‘Girls Can Do Anything!'”

Martin attributes her grit to her father. The two would run basketball drills and shoot for hours after Johnny’s shifts. Every time Martin missed the basket, her daddy would toss the ball back a bit harder, the leather stinging her hands.

CHRISTY SALTERS MET James Martin when she was 22 and he was 47.

“I wasn’t very worldly,” Martin says of her younger self. “I believed in people, believed a lot of bulls—.”

In 1989, on a lark, Martin had entered a Toughman Contest — a brand of low-rent brawls that predated MMA — and fared unexpectedly well. The exposure led to an offer of a professional boxing bout. Martin was meant to be chum for her more established opponent. At the time she accepted the fight, Martin had never been in a boxing gym, never been taught how to punch.

“I beat the s— out of the girl,” Martin says. “They called it a draw.”

Martin immediately booked a second fight. The next month, in Johnson City, Tennessee, she knocked her challenger out. A promoter in the audience, impressed by Martin’s raw talent, advised her to pursue the sport more formally and suggested a boxing gym in nearby Bristol, said he knew a trainer there.

“I was literally like, ‘This’ll be fun for a few months before I get a real job,'” Martin recalls.

When she arrived at the facility (her mother and her pet Pomeranian in tow), she was introduced to Jim Martin, the head coach. Within seconds, it was clear Jim didn’t want her there.

“He hated me,” Martin says. “I walked out. My mom encouraged me to go back and let him train me.”

“I remember that day,” Joyce says. “You could tell that Jim had that attitude that she couldn’t do anything, that girls’ boxing was a joke.” She pauses. “We never thought it would turn into what it did.”

Jim had hatched a plan to have some of his guys break a few of her bones to teach Martin where she did and didn’t belong, a plan he aborted in the end.

As he would later explain to a reporter, “I had it all set up to have her ribs broke. A couple of ribs, anyway. But the boss shows up, the guy who invited her out to the gym, so I thought I’d put that off for a couple of days. How would it look if I had her ribs broke right away? See what I’m saying? But I’m sort of a macho guy, and I didn’t think women belonged in the fight game.”

“I decided I’d stay for six months,” Martin says of her decision to stick it out, never thinking boxing was going to be her career. Or that she might get hurt. “Who was going to hurt me?”

A quick study, Martin swiftly booked local fights, winning many in dramatic fashion. An expert boxer is a master of pace and technicality. Punchers just want to knock you out. Martin saw herself as a puncher first.

“Why go 10 rounds?” she half-jokes. “I get paid the same if I knock you out in the first.”

Over time, Martin turned out to be a great fighter for all the usual reasons and some unexpected ones. An amalgam of technique, will and rage, she had good feet, balletic form, startling reach. She let her strength travel through her body effortlessly like electricity. Fast and potent, she fought years above her training. And she was thrilling to watch.

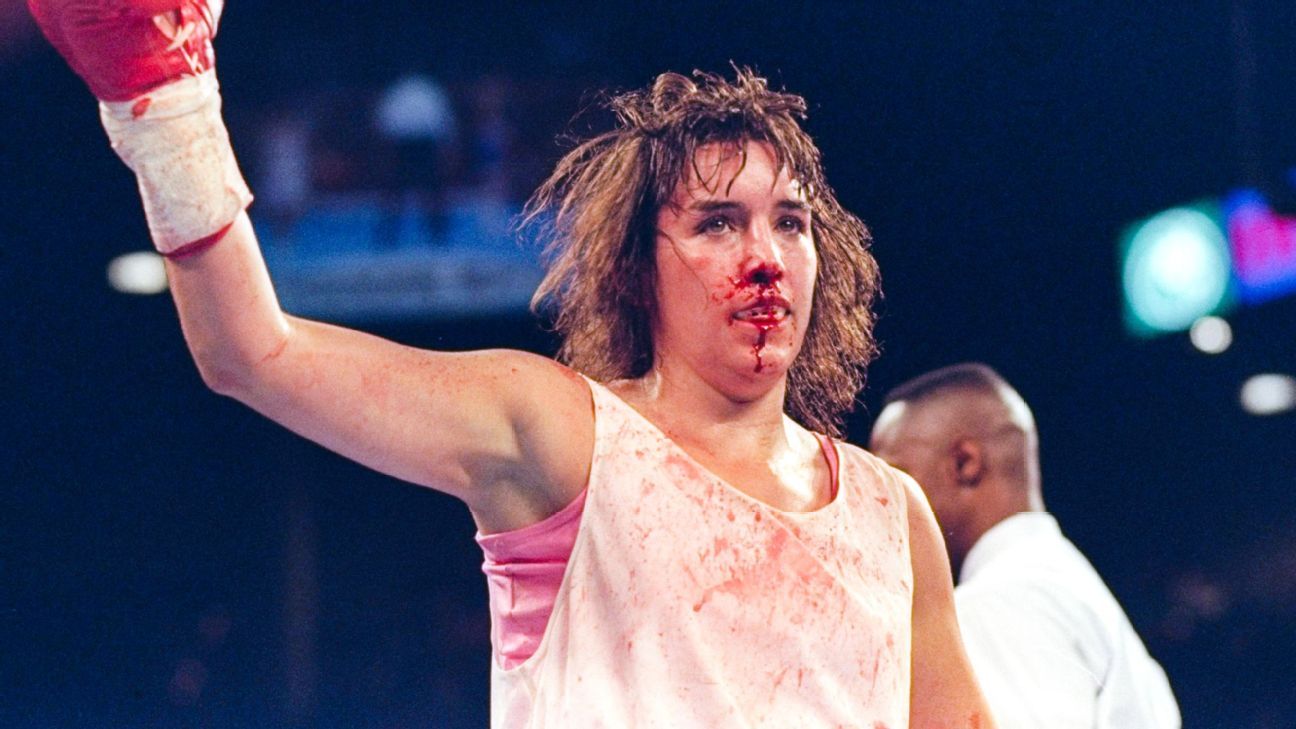

Martin appeared fearless in the ring. She took punches to the face, never shying from the nastiest of blows. Pain was for other people. She was also pretty, high-cheek-boned and twinkly-eyed, with the teased bangs of a heavy metal vixen. The cherry on top: her tendency to compete dressed in pink.

Martin’s astonishing success led Jim to have a change of heart about what women could do. He also sensed a unique opportunity about what this particular woman could do for him.

“He would tell me, ‘I’m going to make you the best woman fighter ever and make myself lots of money,'” Martin remembers. “It was all about what I could do for him.”

Two years after they met, the couple married in Daytona Beach, Florida, at City Hall. Martin knew then it wasn’t love for her. But she needed Jim, or so she thought, and Jim wanted to wed. The newlyweds moved to Orlando to build Martin’s career.

The 1990s are viewed as the golden age for women’s boxing. The field was large. Women with an inclination for combat sport had nowhere else to battle but in the ring. “There was just so much talent,” Martin says.

Martin set herself apart via KOs and media savvy. She leaned into her West Virginia chippiness, fought under the moniker “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” her volatility fueling her cult of personality and her smack talk, enmity she says now was mostly a response to feeling out of her depth.

“What you say publicly and how you really feel is not the same,” she explains. “I wasn’t nice to anyone. I would cuss ’em. I knocked one girl out and spit on her.” A display that put Martin on the radar of renowned boxing promoter Don King. “All the guys in the crowd came up after that fight trying to get around the ring,” Martin recalls. “They had roses for me.”

“Part of it was Jim,” Martin explains of her free-flowing hostility. Jim planted stories in her head, how her pals didn’t really like her. How her family was ashamed of her. Isolated and gaslit, it didn’t take long for Martin to lose her bearings. Everyone became untrustworthy.

“Jim would say, ‘Everybody hates you, you are out here alone.’ He made me feel it’s me against the world.” Martin shrugs. “It was evil, but it wasn’t altogether a lie. It was me against the world in a lot of ways.”

Martin’s fighting style proved popular. She put butts in seats. Her fee soared from the low thousands to $350,000 paydays.

“The turning point was the match against Chris Kreuz in 1994 at a small Vegas venue,” Martin says. “Don King was there with some of his really close people, and they saw how the crowd reacted to me.”

Not long after, Martin became the first woman signed by King, which led to the historic 1996 Vegas matchup against Ireland’s Deirdre Gogarty on the Mike Tyson-Frank Bruno undercard.

Gogarty split Martin’s nose open in the third round, but Martin never flinched. Her wrenching, bloody victory was seen by more than a million fans on pay-per-view, overshadowing the lackluster bout on the main card.

Immediately after her win, Martin’s hotel voicemail filled up with offers and appearance requests. She thought it was a prank.

“Why would people play this joke on me?” she wondered. “Why would they mess with me like that?”

As Martin’s career accelerated, Jim’s hold tightened.

“He wouldn’t allow me to find friendships,” Martin says. “He controlled who I talked to, what I said to them.”

Jim manipulated Martin in other ways too, belittling her accomplishments, taking credit, placing blame. “We would win, I would lose,” she explains. He insulted her appearance, her intellect.

“He told everybody I bled like a stuck hog. I weighed myself three times a day in front of him.”

Jim also read Martin’s emails, her texts. He’d know what she said on private phone conversations. He kept an equally suffocating grip on Martin’s earnings — spending freely on $300 Versace shirts, Hummers, Harleys, jewelry for himself — never telling Martin where the money went or how much remained.

At some point, Jim introduced surveillance to the mix, filming his wife in compromising and humiliating positions, with and without her knowledge. He installed secret cameras in the bathroom light fixtures. Sometimes he showed the photos and DVD recordings to his friends.

Jim mentioned the images every time Martin started to feel good about herself, inched toward pulling away. He said he’d disseminate them to everyone who mattered to her or her career, reveal them to her mother, her daddy.

“Jim controlled every aspect of Christy’s life,” says Florida state attorney Deborah Barra, a specialist in trying sex offenders and domestic abusers who prosecuted Martin’s case. “He was vindictive. He told her nobody would love her but him. She believed she owed him everything.”

Martin was most uneasy about Jim’s connection to her family, how seamlessly he’d insinuated himself into their good graces, the trust they placed in his decision-making.

“You know, I always loved Jim,” Joyce says softly. “I always thought he looked after her and protected her. But I found out different. She kept it hid from us. From everybody, really.”

Asked if she ever saw any clues as to who Jim truly was, Joyce chews on the question, then answers.

“After she married Jim, she pulled away. She’d talk, but it didn’t sound the same, you know? Or I’d call and Jim would say, ‘She’s in the shower’ or ‘She’ll call you later,’ but she didn’t.” Joyce pauses, collects herself, signals she’d like to move on, then changes her mind.

“Jim had this way. He could say something to you that he wanted you to think it was a compliment, but it was really a put-down. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s just how he was.”

Before Martin’s fighting run ended in 2012, she earned $4.5 million from boxing. She guest-starred on “Roseanne,” appeared frequently on Leno, “Good Morning America,” the “Today” show. She traveled the world. Celebrities shouted her name in airports. She was Itmann’s hometown hero, a role model for women athletes the world over. But what sticks with Martin most is the loneliness.

“I remember being in the casinos in Vegas so many times, walking and imagining how awesome it would be to be on this ride with somebody I really love, somebody that cared about me,” she says.

Instead, she had Jim.

“For 20 years, Jim told me he was going to kill me if I ever left him. At first, I didn’t think he was serious. But then time went on. And I realized.”

PREDATORS AREN’T SPECIAL. Their fetishization in popular culture as evil geniuses belies a far more pedestrian truth: Their one real skill is sniffing out anguish and capitalizing on that discovery. It’s the easiest thing in the world to convince a miserable person that they’ve earned their misery, to say out loud the horrible things they say to themselves. To hold up a mirror.

Deana Gross owned the La Ti Da Salon & Spa in Apopka, where Martin got her hair done. Over the years, the women became friends. When Martin offered her boxing gym as a place for Gross to exercise, Gross happily accepted. Then things got weird.

Sometimes Gross would be working out and notice Jim scrolling through Martin’s phone while Martin was in the locker room or she’d catch him hovering by the whirlpool, watching Martin. Other times, Jim would follow Martin to the La Ti Da, sit in the parking lot and stare through the car window as she got her cut and color.

Jim wasn’t at the salon on Nov. 23, 2010, when Martin dropped in to confide to Gross that her marriage was over.

“Christy looked really good and happy and peaceful,” Gross told the court when she testified as to the events of that day. “When she left, she was walking away and she told us that she loved us.”

The sentiment was unusual. It stuck in Gross’ memory.

“I was telling them goodbye,” Martin explains now. “They didn’t know, but that’s what I was doing. I’d been married to him 18 years. I was 42. And I was ready to die.”

Martin had made the decision while driving her Corvette, head pounding as the miles ticked past, the numbing flatness of the Florida highway speeding her toward what she believed was an immutable fate. She refused to be chased the rest of her life. She needed to live through whatever this man was going to dish out. Or die trying.

So Martin phoned her closest friends, said her secret goodbyes, her I love yous. And as she rounded the corner of her street, she was as certain as she had ever been that whichever ending happened was OK with her, because live or die, she would finally be free.

MARTIN MET SHERRY LUSK in eighth grade, 1979. They played basketball together in Itmann, grew close. By the time Martin was in high school, they’d begun a clandestine romance.

“All the time, you’re battling in your brain about who you are,” Martin remembers. “What you are, what you really want to be. I was young, but I loved her so much.”

It was the ’80s in Appalachia, Martin’s only frame of reference outside of family summer drives to Daytona Beach.

“I didn’t know if there was a place where everybody was more open with their sexuality,” she says. “I just knew it wasn’t in West Virginia.”

As teens, Lusk and Martin invented reasons to spend time together. Forbidden hours stolen like candy. Time that made them feel both right and wrong.

“In high school, Sherry was here at the house a lot,” Joyce says. “I had no idea she was gay then, that they had a relationship.” She clears her throat. “I don’t think anybody says, ‘I’m happy my child’s gay.'”

When you hate who you are, when you’re convinced it’s wrong, sinful, when you lug around the desires of your heart like a corpse, when the only feelings that give you life are the same feelings that make you wish you were dead, you begin to shrink, to swallow yourself spoonful by spoonful.

“I’ve been hiding who I truly am since I was 12,” Martin says.

The smaller you get, the happier those who see you as a source of ignominy become. So you keep eating yourself alive, you do it until you choke. You convince yourself it’s what you deserve. You unleash so much violence on yourself you barely recognize when the violence comes from somewhere else. It doesn’t even feel like violence anymore. It feels like truth.

The day before Martin decided to marry Jim, Jim called her daddy and told him he’d caught his daughter with a woman. According to Jim, Martin’s father told him to throw her out, to toss her belongings in the street. According to Jim, Martin’s father said, “We don’t want her either.”

The next day, Martin and Jim went to the courthouse and said “I do.”

“I believed in order to have my family, I needed to be with a man,” Martin says flatly. “I didn’t really have a choice.”

If you convince yourself you can never be yourself, you enter a fugue state, a life half-lived. Sometimes you get lucky and a person comes along and snaps you awake. They smile when you walk into the room, and the cloche you’ve carefully balanced over your “Truman Show” fantasy world shatters like the razor-thin facade it always was.

In March 2010, a Facebook alert popped up on Sherry Lusk’s screen. People you may know: Christy Martin.

Lusk laughed out loud, then sent a message: “Hi, how you doing?”

The reconnection led to texts, which led to phone calls. The conversations led Lusk to suspect her old friend was in danger. “It seemed as if she had no hope left,” she explained in court.

Martin disclosed to Lusk that she was abusing cocaine, having started using in 2007. According to Martin, Jim was her supplier. He held cocaine over her head like a treat for a dog (something he denies).

“He knew I would just about do anything for it,” Martin explains. “I was f—ed up all the time. I didn’t want to be in reality.” Sometimes a voice in her head said, “Just overdose, overdose, overdose.”

Lusk asked Martin repeatedly why she didn’t leave her husband. Martin said she wouldn’t survive.

The women agreed to meet face-to-face on Nov. 18, 2010. Questioned under oath if that rendezvous was romantic in nature, Lusk said it was “to help a friend.” For her part, Martin was upfront and told she was going to meet Lusk for lunch.

They chose a café in St. Augustine. During the meal, Martin’s phone blew up with texts and calls from Jim. She ignored them at first but eventually began to play them aloud for Lusk to hear.

“He kept saying he was going to destroy her,” Lusk testified.

Jim then texted a still from a video he had running on a television, a screen grab of his wife using a sex toy. Jim had moved Martin’s personal items into the frame so there could be no mistaking who it was.

The next time the women met was four days later in Daytona Beach, Nov. 22. When Martin greeted Lusk in the Comfort Inn parking lot, she grinned, hugged and kissed her hello. Martin’s phone rang immediately. It was Jim.

“I followed you.”

Terrified, the women raced into the hotel and hid.

A few weeks before she saw Lusk, Martin had told Jim she wanted to divorce him. She’d contacted a lawyer, planned to file paperwork. The couple made a deal to live together until her next fight, after which they’d split the purse and officially separate. Buoyed by the plan, Martin quit using coke, amped up her training. The future was as bright as it had been in two decades.

“Christy realized there were other options out there, that other people would care about her,” Barra says. “It took connecting with another human being to remind her she was special.”

When Martin told Jim she was going to visit Sherry, per their new arrangement, “he said, ‘Can I go?'” Martin recalls. “I’m like, ‘No.’ And then he said, ‘If you go, I’m going to kill you.'”

Minutes after that first call in the parking lot, Jim sent a text.

I’m so close to you, I could touch you.

The last words Martin said to Lusk before she left Daytona to return to her home in Apopka were, “This motherf—er is gonna shoot me.”

“Jim told me he was not afraid of going to prison for killing me,” Martin explains. He told her he knew people who could make her disappear. He referred to these threats as promises.

IN THE APOPKA emergency room, it took two hours for doctors to stabilize Martin, her lung, punctured in two places, initially refusing to reinflate. As soon as it could, a medical team life-flighted Martin to a larger trauma hospital in Orlando, where surgeons stitched her leg back together, warning that she might not walk again. They sewed the lacerations on her head, her side, reattached her ear. The bullet in her chest would stay put for a few more weeks, until the police needed it extracted for evidence.

“Blood covered every part of her body,” Lusk testified of Martin’s condition in the ER. “Her hair was matted full of blood. They kept trying to get a tube in her. She was screaming.” And then there was the severed calf. “You could see everything, the tendons, the muscles, veins. Just laying out there.”

Joyce Salters had been struggling to get in touch with her husband and son. They’d been deer hunting when she got the call from the hospital. After she ultimately reached them, she told John, “Sis and Jim have been in a fight.”

When the Salters family arrived in Florida the next day, they spoke with the local marshal. Martin had been admitted under a different name for her protection.

“They wouldn’t let us see her until they knew who we were,” Joyce says. “They were worried Jim or someone would come in and harm her.” (After discovering Martin missing, Jim had fled the scene and would be discovered a week after the attack hiding in a neighbor’s shed.)

Joyce says that when she was at last able to lay eyes on her daughter, it took her breath away. “She had tubes running everywhere, stitches all over her head, on her face. It’s something you never forget.”

Joyce was relieved when she learned Martin was able to speak. The first thing her daughter said to her? “I told you he was crazy, Mom.”

Earlier in their marriage, Jim had punched Martin in the mouth so hard her tooth pierced through her lip. The day it happened, Martin went to the bathroom to clean herself up. As she blotted her face, a few spots of blood dripped onto an obscured section of the wall. Martin decided to leave them there. For years, she’d carefully clean around the bloodstains, taking care not to erase them. Proof of life.

“That’s what you do when you already know that’s how it’s going to end,” she says.

THE FIRST FEW YEARS after the attack, Martin dreamed she was running, running, running. As she runs, she’s screaming, “He’s killing me!” Sometimes she dreams Jim’s jumping out of the closet. Sometimes she wakes up to the sound of her own screaming. Sometimes she punches in her sleep.

Her wife, Lisa Holewyne, 54, tries to soothe her, but the nightmares make her sad. This man still living in Martin’s head. Still terrorizing.

“She has PTSD,” Holewyne, herself a former boxer, says, offering an anecdote about how she recently pulled out a knife to chop food and Martin jumped, then apologized.

“I told her, ‘I don’t need you to say sorry. I just need you to know that I’m not him.'”

Martin admits she still feels surveilled.

“Even now in the shower, I get freaked out because I’m thinking somebody is watching me,” she says. “Domestic violence is about control. The bruises heal. But mentally? It never goes away.”

Martin swore to herself she wouldn’t be vulnerable again. “And then in four months I was married to this woman,” she says of Lisa, laughing.

The couple, who wed in 2017, proposed to each other in a hotel parking lot. They’re grown, they explain, thus the lack of clichéd romance. They knew what they wanted.

Holewyne, now in the construction trade, says she met Martin when “she punched me in the face.” It was 2001, and they fought on the undercard of the Hasim Rahman-Lennox Lewis heavyweight championship rematch. The fight was at Mandalay Bay in Vegas, Martin’s last gig for Don King.

“It was the best fight that I fought, strategy-wise,” Martin says. “I had to be at my A-game to come away with the win.”

“She boxed circles around me,” Holewyne corrects. “It was aggravating. At the weigh-in, when I got off the scale, I said, ‘Good luck, Martin,’ and she said, ‘Good luck getting knocked the f— out.’ Those were our first words to each other.”

Martin says she didn’t want to fight Holewyne. She’d seen tape, knew that Holewyne was no joke. The weigh-in taunting was strategy.

“I knew I had to make her mad so she’d make a mistake, and when she did, I’d take advantage of that mistake,” Martin says. “It was all a game. I did that my entire career.”

Laying out a spread of chorizo tacos and chips, the couple reminisce. They rib each other about their respective records. Holewyne mentions the current undisputed middleweight champ, Olympian Claressa Shields.

“She talks about how she won a gold medal and whatever,” Holewyne says of Shields. “But look, she has a 20% knockout ratio.”

Martin has knocked out more than half her opponents.

For most women boxers, Holewyne points out, Martin opened the door to imagining boxing as a viable career. “Christy was the only money girl in the sport. We all wanted what she had.”

Holewyne stops herself, recognizing that what Martin had might not have been exactly as advertised.

After Jim went to prison, Martin realized she didn’t even know what she liked to watch on television. She didn’t know what foods she preferred. Their whole marriage, he’d left her alone for two nights. Martin hadn’t had the space to consider her own wants for two decades.

Holewyne remembers one time when Martin was sick, back when they were just colleagues on the women’s circuit. Holewyne came by to visit, brought Martin tea and honey, asked if she had a thermometer in the house. Martin couldn’t remember where it was, so Holewyne bent down and pressed her forehead to check Martin for fever. The tenderness floored Martin.

“No one had ever done something so nice for me,” Martin says.

“I made her tea, and it was earth-shattering to her,” Holewyne says. “That was hard for me. If you come up in boxing, you believe that Christy Martin is up here and that all the rest of us are somewhere down here. It seemed like she had it all.”

AT THE TRIAL of the State of Florida vs. James V. Martin, Christy Martin took the stand for three hours. She revealed every prurient detail of her history, her cocaine addiction, her sexuality, the sex tapes, the sex toys, the suicide attempts. When she held a gun to her head, Jim would say, “Chicken, go ahead, pull the trigger.” When she swallowed pills, he’d urge, “Take some more.”

Martin opened each mortifying page of her psychological diary and let a roomful of strangers (a larger number of folks than lived in her hometown) probe her weaknesses and mistakes and humiliations.

“At some point during the attack when I was getting shot and stabbed and praying to God to help me, I guess God’s spirit did get in me and changed the way my heart felt,” Martin told the court, explaining to the jury that though she was prepared to die, she decided she wanted to live.

So she got off the floor, like so many boxing mats. She ate her pain and embraced her suffering and realized that if she was going to survive, she was going to need to walk away from everything she’d ever known, and she’d need to walk alone.

Her testimony finished, Martin hopped down from the stand. She hadn’t seen Jim face-to-face since the day he left her for dead. And there he was, legs shackled, arms free, slouching at opposing counsel’s table, blankly listening to the sordid saga of the 20 twisted years she’d endured with him.

Martin was supposed to pass between the tables in the designated walkway for witnesses. Instead, she made a sudden turn and beelined for Jim.

The prosecutors watched, frozen with dread, worried that Martin might break, throw a punch or worse. Quickly arriving at Jim’s seat, Martin leaned over, her nose inches in front of Jim’s gaping mouth, eyes locked on his.

“I hope you rot in hell, you motherf—er,” she said, her voice calm, firm, resolved. Martin paused a beat, then slowly, defiantly walked away.

“It was like, holy s—,” remembers Barra. “In 115 trials I’ve done, the victim has never done that. Everybody was stunned.” (Barra later made the whole legal team mugs printed with Martin’s quote.)

Jim pleaded not guilty to charges of attempted first-degree murder, attempted manslaughter and aggravated battery. When he finally took the stand, he contended he wanted to address the court not to “bash Christy” but to “tell the truth.”

A few moments into a meandering statement, Jim admitted, “I guess I made a mistake by not entering a plea of self-defense.”

In court, Jim’s team failed to establish grounds for self-defense, an argument Martin’s lawyers had been prepared for, expecting him to use Martin’s boxing background against her. When the argument never came, Barra and her colleagues were baffled.

“I don’t think he could bring himself to lose his man card,” theorizes Barra of the bizarre choice. “He had such an inflated sense of self. I mean, he tried to sell his prison ID on eBay.”

As Jim’s final statement unspooled, he insisted his marriage to Martin was fraught but grounded in mutual affection.

“I’m so, so bad that we spent 20 years together?”

Jim insisted he didn’t stab his wife. Didn’t shoot her. Didn’t cut her calf. That a gun misfired during a struggle.

“So your theory is a bullet magically ricocheted down, cut her calf in half, bounced back and just happened to end up in the middle of her chest?” lead prosecutor Ryan Vescio asked incredulously during cross-examination.

“It’s my truth,” answered Jim, concluding, “We were together 24/7. Nobody stays with anybody 24/7 unless they love each other.”

It took the jury five hours to find James Martin guilty of second-degree murder. Jim was sentenced to 25 years, the mandatory minimum sentence, which would make him 93 years old at his scheduled release. He has suffered a stroke and is in ill health. Martin says she thinks about visiting him. She carries a running list of questions on her phone that she’d like to ask him, questions like, “When was the exact moment you decided to kill me?”

Martin knows any answer she gets would likely be a lie. But still she keeps the list.

“I wish I wouldn’t have ever met him,” Martin says. “But then I would never have been the boxer I am.” Her success, the fame, the money, the shadow life, it was all knotted together, a teeming rat king, one tail indistinguishable from the next.

“I should have been willing to leave everything and be happy. But I wasn’t there yet.”

DURING MARTIN’S HEYDAY, her mother would come to fights with a Mason jar full of moonshine. After Martin finished her bout, Joyce, Jim and the team would gather at the hotel bar to celebrate. While Jim held forth, Martin would get drunk on tequila, shot after shot, trying to erase herself in real time.

“I could never have imagined it,” Joyce says of her daughter’s professional achievement. “The places she went, the people she met. One time we were in Vegas and somebody hollered at her and I said, ‘Who was that?’ And Christy said, ‘Who do you think it was, Mom?’ And I said, ‘Sugar Ray Leonard.’ And she said, ‘Well that’s who it was.’ People like that, they knew her. They talked to her like she was their friend.”

Joyce says she has always marveled at her daughter’s work ethic, her character. She left her daughter’s bedroom just as it was when Martin moved away from West Virginia. Beer stickers on the wall, a poster of a woman splayed on the hood of a Corvette, back arched.

“The people here in Itmann are so proud of Christy,” Joyce says. “Every time I see somebody, they ask, ‘How’s Christy doing?’ She hasn’t really been here a lot in the last 20 years, you know.”

After she married Jim, Martin believes her mother took his side in arguments, relieved her daughter was living a conventional life, as much as a woman boxer could. Jim wasn’t ideal, but Jim was welcome at the table, Jim required no explanation at church.

“She would say, ‘I know he’s controlling and he’s this and he’s that, but …'” Martin recalls coolly. “My mom didn’t want me to be gay. She was happier to believe what Jim said than to hear the truth from me. People wonder how did I stay in a relationship with someone that was abusing me mentally, emotionally, physically?”

Martin takes a deep breath.

“Sometimes I think that if my mom would have just been OK with who I was …” Her voice trails off.

Martin has confronted her parents about those early days. The shame, the rejection. They tell her it was a long time ago, that they don’t remember.

“I was shocked that he hurt her,” Joyce says. (Johnny prefers to let Joyce do interviews, but Martin says she and he remain tight.) “Jim had us all fooled.”

As for Martin’s sexuality, Joyce explains, “I never quit loving her. Some people would say, ‘I’m not going to have anything to do with you.’ But if you love your child, I don’t see how you can do that. It’s hard. But I’ve come to the conclusion that it is between her and God. It’s not for us to judge.”

Martin wishes she were closer with her mother. They talk several times a week, they love each other, but a wall remains, one fortified by avoidance and selective memory and religion, and neither woman has the stomach to tear it down and pick through the rubble. Martin knows that some of the distance is her fault, that when you bury yourself alive, it’s hard for people to find you.

“Sometimes I think she thought I knew what was going on,” Joyce says. “Like, why didn’t I do something about it? But I had no idea. I really don’t know what I could have done.”

“When we were getting married, Christy had a conversation with her mom and it was a tough one,” Holewyne says. “Her mother has tried very hard. You can see her stretching and you can see it’s not instinctual and you can see that she almost doesn’t want to do it, that she has to take a breath and smile.”

Holewyne labors to inch her wife toward letting go, toward reopening her heart. Martin prays on it but remains wary of forgiveness. Even so, like any daughter of West Virginia, she accepts what is.

“I don’t think people realize how sensitive Christy is,” Joyce says. “She portrays being tough and all that, but she’s a gentle soul.”

Joyce says she still thinks about Jim. How close they all were. How all that closeness turned to poison. She says Jim should be glad that Christy’s daddy and her brother never got ahold of him, that they didn’t find him before he went to jail.

“Jim was always good to me, he was,” Joyce says. “But I’d want to ask him: ‘How could you do that to somebody you love?’ You know, he said he loved her even at the end.”

IT’S FEB. 8, 2020, and the Avalon Ballroom at the Hard Rock Hotel Daytona Beach is filling up early for Battle at the Beach II. Deep rows of chairs circle the boxing ring in the center of the room, a handful of VIP tables tucked in the rear, denoted by tablecloths and “Christy Martin Promotions” koozies printed with pink boxing gloves. In the corners, full bars are stocked and ready, ice melting in large coolers. Ring girls arrive, unzip their hoodies, fluff their cleavage, smooth their edges. The first fight is scheduled to begin at 5 p.m. Martin likes an early start. “Like Don King,” quips referee Frank Santore Jr.

One flight up, boxers dressed in sweats and slides (a few lucky ones in satin jackets embroidered with their name) are briefed on the local rules — three knockdowns, you’re out; hit an opponent when they’re down, lose two points. Thirteen bouts are scheduled, purses $600 to $6,000. “Good luck and God bless,” the official says.

Amid it all, Martin circulates, dressed in a crisp white polo button-down, dark wash jeans and pink patent loafers. She reviews the press table, the ring, checks her watch every few minutes. Holewyne does her own laps, helping where she can, steering clear where she can’t.

“She’s grouchy on fight night,” Holewyne says of her wife, adding an affectionate eyeroll. As she does, Martin strides past, grumbling “Lord have mercy” under her breath.

For many, boxing remains an exit ramp to something better, a path to dignity for the poor kids, the forgotten, the overlooked, the inconvenient. In a universe of uncertainty, boxing offers the explicit promise of knowing your value. A simplified yardstick. You enter the ring and you prove who you are, or aren’t.

“I was at Christy’s first fight as a boxer,” Santore recalls. “She knocked her opponent three rows back.”

The music begins blaring and Martin perks up. “Now it’s boxing,” she proclaims, smiling.

Young Latinx families file in, filling seats along with middle-aged couples of all races, groups of women, 20-somethings dressed in shiny clothes on dates. Martin shakes hands, pats shoulders. She smiles, flirts, banters, makes folks feel at ease, thanks them for coming out. She remembers names.

Cheese, grapes and saltines arrive at the VIP tables, one of which is occupied by Evander Holyfield, on the scene to watch his son Evan fight Travis Nero from Oklahoma. (Holyfield takes off immediately after Evan wins in a first-round KO, every phone in the place recording his exit.)

All evening Martin continues to mingle, keeping one eye on the fights, offering a running commentary. “That boy has his chin up way too high. … He’s slow. … I thought this would be a better matchup …” Martin knows boxing like she knows the road to her childhood home.

As the last fights play out, Martin finds a quiet space behind the merch table. She signs T-shirts, poses for photos with fans. The spotlight hung for the ring beams in her eyes. She lifts a hand to shield the glare. On the wall behind, she casts a giant shadow.

Half an hour later, the fights are over, and Martin and Holewyne have hit the Hard Rock rooftop bar for the after-party. The gathering is a blend of fans, boxers, trainers, back-in-the-day friends, new acquaintances. Everyone gobbles down chicken wings and champagne. Martin and Holewyne drape their arms around each other, toast to the success of the night.

Old pals buy the pair shots and chatter about Martin’s early fighting days. “I knocked out 31 people, so I guess I did OK,” Martin jokes of her legacy. Eloise Elliott, Martin’s physical education teacher from Concord University, tells those gathered around a nearby table how aggressive young Christy was on the basketball court, how sociable she was in class.

“She babysat my kids,” Elliott recalls, then drops her voice to a whisper. “After she married Jim, we never talked much.” She pauses, looks around. “It’s hard for people in West Virginia to find their dreams sometimes.”

Someone asks what Martin thinks made her such a good boxer, likely the best woman of all time. Martin thinks for a beat before answering.

“I didn’t want to let anyone down.” She says it again. “I didn’t want to let anyone down.”

A FEW MONTHS AFTER Battle at the Beach II, Martin is back in Texas, quarantining at the condo she shares with Holewyne. To stay busy, Martin is pulling together her next promotion — a series of 15 fights she hopes to hold July 11 at the National Guard Armory in St. Augustine. It will be her 15th event since she began promoting in 2016. (The venue will not be open to the general public and will go through the Florida-mandated COVID-19 protocol, with testing to be conducted at weigh-in.) She won’t make any money. But it’s worth it to her to keep her hand in the game while the virus runs its course. She wants to control what she can, as long as she can. And right now, that’s Christy Martin Productions.

“There’s been so much turbulence my entire life,” she says. “I just want it to be smooth.”

She and Holewyne haven’t fully settled into their rental. When they find the right spot, the couple plan to build, somewhere remote. For now, Martin’s many championship belts and honors idle in boxes stacked against the walls. Martin thinks maybe she’ll move her memorabilia to her grandmother’s house in West Virginia, “make a cool little Hall of Fame to myself.” She purchased the 90-year-old coal camp when her grandmother died. Asked if she sees herself ever living there, Martin laughs.

“Hopefully not.”

When you drive into Itmann, a modest sign announces you’re entering, “The home of Christy Salters Martin.” Martin says it’s never occurred to her to snap a photo in front of the marker. More than most, Martin understands you can’t go home again.

She confides that she’s recently had an epiphany.

“I used to think I loved Sherry,” she says. “But I didn’t. Not really. I was in love with how I felt being me.”

Martin clarifies that she’s not trying to be unkind, it’s just that in this mandated quiet time she’s realized what she’s been chasing for 40 years. Back before she sank her wants to the bottom of the ocean. Back before she was defined only by the fight, by the punches she withstood. Back when she was just a girl too naive to know she was just a girl. Before the safest place she could imagine was the center of a boxing ring.