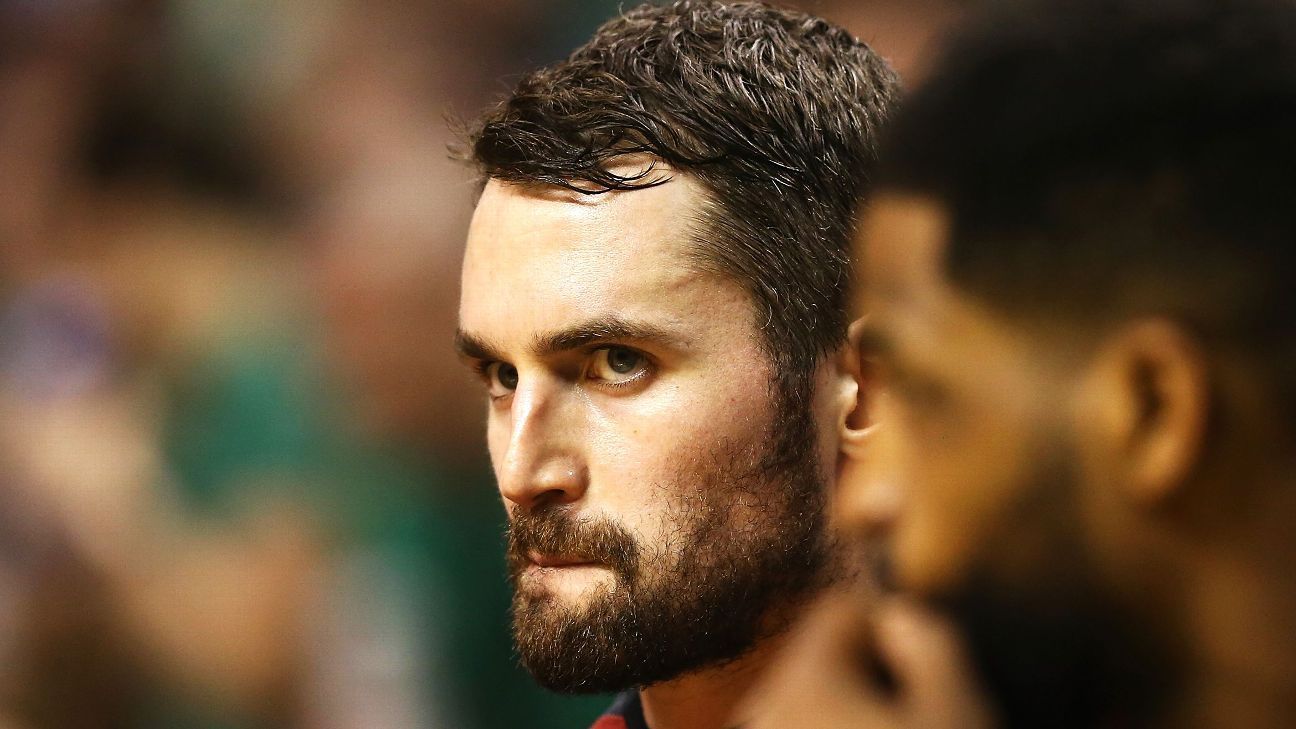

Kevin Love is fretting about COVID-19.

He’s not spending a lot of energy worrying whether he’ll get it, or grieving the death someone of close to him who contracted the coronavirus. He frets because he knows what can happen if people experience the loss of a loved one, become consumed with the loneliness of isolation, experience job insecurity and financial difficulty, and then internalize that stress instead of getting help by reaching out and talking to a health professional.

“Listen, I don’t have all the answers — and likely never will,” the Cleveland Cavaliers power forward said. “But speaking from experience, I can tell you there are resources out there that can help you.

“It’s really scary what’s going on in the world right now. But you don’t have to suffer through it alone. Take it from someone who did that for far too long.”

In August 2018, Love sat down with ESPN to publicly address his mental health struggles. He revealed a detailed account of a panic attack he’d had in the middle of a game against the Atlanta Hawks the previous November, when his heart began racing so fast, he felt it was going to pop out of his chest. Struggling to breathe, Love stuck his hand down this throat in hopes of dislodging whatever was blocking his airway. There was nothing there. His panic attack left him splayed on the floor of the locker room, believing he was about to die.

Since then, Love’s life has been transformed. He has assumed the mantle as the face of mental health awareness, not just for the NBA but across numerous sports, educational and cultural platforms. He created the Kevin Love Fund, an organization committed to normalizing the conversation about mental health.

And, with May designated as Mental Health Awareness Month, he’s continuing to spread his message in these uncertain times that people should “pursue mental wellness with the same vigor they do physical health.”

“My life is dramatically different,” Love told ESPN. “I have a lot more clarity about where I’m headed, and where we’re headed as a society in terms of removing the stigma from mental health issues. We still treat mental illness so differently from a physical illness. If you had a heart condition, you’d see a doctor and you’d take the necessary steps to fix the problem. Why should it be any different with mental health?”

Love has gradually peeled back the layers of how he has managed to continue to play basketball while taking a proactive — and public — approach to managing his mental health. A major part of his treatment, he says, is cognitive behavioral therapy, a problem-focused technique that centers on changing negative thoughts, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors, and providing coping strategies to help a person improve their ability to regulate emotional responses.

But, Love discovered, cognitive behavioral therapy on its own wasn’t enough for him. He realized he needed to pair his treatment with medication. That comes with added scrutiny. Some of Love’s NBA brethren, who he said could benefit from medication for a variety of mental health issues from ADHD to bipolar disorder, have rejected taking that step because they are embarrassed, consider medication a sign of weakness, or are afraid of the negative connotations associated with it and how it could affect their standing with the team.

“I know some guys don’t want to go there, but taking medication has changed my life in a big way,” Love said. “It has helped me manage this ongoing feeling of irritability, this feeling in the pit of my stomach that I couldn’t shake before. The medication helps me relax without sapping my energy levels.

“I have been battling depression my whole life. And when my mind starts to spiral, the meds help me to decompress, and make it easier for me to escape going to that dark place.

“If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that my struggles with mental health aren’t ever going away. That’s just not a reality. The medication helps me feel a little better in my own skin and my own brain. Whatever imbalance I have, this has helped me find more relief.”

Love emphasized that medication is not for everyone and that it’s imperative to settle on the correct dosage, which may require trial and error. Love consistently coordinates his treatment with the Cavs’ team doctors, the athletic training staff and his personal physicians. (For now, he said, he’d rather not divulge what medication he’s taking.)

The Kevin Love Fund has partnered with organizations such as the mindfulness app Headspace. Together they have provided student-athletes at UCLA, Love’s alma mater, with subscriptions to incorporate into their training programs. Love works closely with Michelle Craske, a UCLA professor of psychiatry, psychology and biobehavioral sciences who has done groundbreaking work on anxiety and depression. “They should put up a statue for her,” Love said. “She’s brilliant.”

The Kevin Love Fund has also joined forces with the Just Keep Livin Foundation, founded by actor Matthew McConaughey and his wife, Camila, to empower high school students to lead more active lives and make healthy, informed choices. Their program includes fitness drills, service projects and tutorials on nutrition. Love joined one of their Zoom calls on May 10.

The most rewarding part of his role as a mental health spokesman, he said, is making a difference with kids, some as young as preteens. Last year, he counseled a 9-year-old girl who suffered debilitating, repeated panic attacks and considered suicide. Her father reached out to Love shortly after he publicly discussed his own experiences, so Love invited the girl to a game and bought her a small stuffed animal to calm her when she felt a panic attack coming on. He did the same for a young boy who had severe depression but has shown improvement following his regular Instagram interactions with Love.

“Hopefully, it’s given those kids some fresh air,” Love said, “a way for them to feel there’s someone out there who can relate. It’s been a form of therapy for me, too.”

The Cavaliers recently opened their practice facility on a restricted basis, but Love discovered when he was isolated from his teammates and his coaches that he needed to establish a routine and stick to it to maintain an even keel.

“I have to be a creature of habit,” Love said. “If I don’t stay in my routine, then I start feeling like I’m not doing enough, or not working towards anything, and then my mind can start to spiral downward.”

Those routines, he said, can be as simple as reading for an hour every night, taking an ice bath, doing some stretching and meditation, or setting aside a predetermined block of time to address his business ventures.

Love has been in contact with schools and universities throughout the country that will emerge from the pandemic underfunded and underserved. He is also lobbying for more mental health funds. Congress has allotted millions of dollars for medical relief from the virus, but only a small amount is earmarked for mental health. Love points to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll that says that more than half of all Americans say the coronavirus pandemic has harmed their mental well-being.

Some of those Americans undoubtedly play professional basketball, but Love laments that even after all the work the NBA has done to remove the stigma, players remain hesitant to address their mental health.

“Guys don’t want to reveal too much,” Love said. “There are so many people who still perceive this as a weakness. Players get scared if they talk about mental health, it will affect their future. They worry, ‘What does my owner think? What does my GM think? Is he going to trade me?’ I was lucky. The Cavs have been incredibly supportive.”

He prefers not to look back too intently on two years ago, when his mental health struggles were undiagnosed, misunderstood and on course to sabotage his life.

“It robs you of your human potential,” Love said. “And it’s terrifying. But, for me, I’m happy to say, it feels like a long time ago.”