IN “THE LAST DANCE,” Michael Jordan professes his love for Scottie Pippen, anoints him the best teammate he ever had and acknowledges he couldn’t have reached pro basketball’s zenith without him. But Pippen has been notably silent since the documentary began its run last month, and those close to him say he’s wounded and disappointed by his portrayal. One of his most famous ex-teammates — a former fierce rival — has even felt compelled to come to his defense.

By his final season in Chicago, Pippen was so bitter about being underpaid — he was the subject of constant trade rumors — that he eschewed offseason surgery on a ruptured tendon in his ankle and instead waited until the start of the 1997-98 season. It was a decision his coach, Phil Jackson, said he understood. Jordan did not.

“I thought Scottie was being selfish,” Jordan declares in Episode 2 of the documentary.

Some 23 years later, the rebuke stings with the pang of a fresh wound. Pippen’s sensitivity is his greatest attribute but perhaps his biggest blind spot. In this week’s installment of “The Last Dance” (9 p.m. ET on ESPN), the film offers a withering examination of Pippen’s infamous decision to refuse to enter Game 3 of the 1994 Eastern Conference semifinals in the final seconds, because Jackson drew up the last play for Toni Kukoc instead of Pippen. It’s compelling footage that picks at a scab nearly two and a half decades old, and includes a stunning comment by Pippen himself that reveals the residual scars of that incident.

Pippen is proud, gentle and soft-spoken, a complicated competitor who somehow never seemed to get his due. An immense talent who chose a long-term but underpaying contract to assist his large family, including a disabled brother and a father felled by a debilitating stroke. A sidekick who embarked on a quest with Jordan for an elusive championship, yet in a Shakespearean twist, struggled in a conference finals Game 7 in 1990 because of a crushing migraine, leaving the Chicago Bulls to fall to their nemesis, the Detroit Pistons.

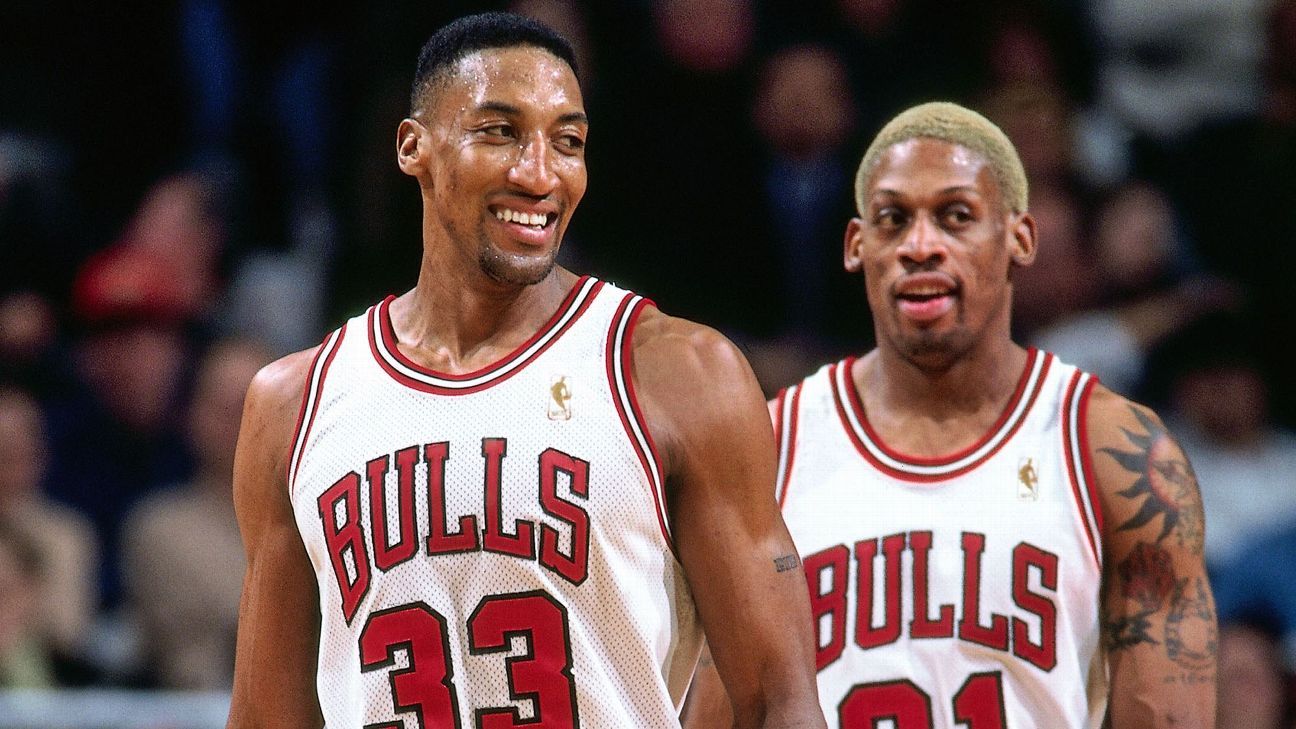

Dennis Rodman, a member of those Pistons teams before becoming the third comrade-in-arms for the Bulls’ final three championships, wants to set the record straight on Pippen. “I wish he didn’t give a s— like me about what people say,” he says.

Pippen should be remembered as one of the best two or three to ever play the game, he says, “but no one could ever quite see him. He was too quiet, and he was always standing next to Michael Jordan.”

From unlikely prospects to hostile opponents to teammates and now the subject of a 10-part docuseries, Rodman and Pippen have bonded over the experiences unfolding each Sunday night, Rodman says.

“Scottie was so underrated — and so underpaid. He should be holding his head up higher than Michael Jordan in this documentary,” Rodman says. “I think a lot of people are now realizing what he went through. The kid was a hero, in a lot of ways, during those great Bulls runs.”

MORE: Ranking the greatest individual seasons in NBA history

ONCE HIS MORTAL basketball enemy, Rodman now considers Pippen “my brother,” a notion that would have been laughable 29 years ago. Then a card-carrying member of the Bad Boys, Rodman viciously fouled and shoved Pippen toward the stanchion during Game 4 of the 1991 Eastern Conference finals, leaving the dazed Chicago forward with a gash that required six stitches to close.

“Yeah, that was quite a push,” Rodman says. “At the time, I was frustrated. Our team was losing, so I said, ‘Screw it.’ I wasn’t trying to hurt him. We were at that point where we knew we couldn’t beat Chicago — our time had come and gone — so we kind of surrendered the whole thing in the fourth quarter.”

The vitriol following the Bulls’ sweep of the Pistons revolved around the notion that the Bad Boys had gone too far, from physicality to violence, with Rodman’s cheap shot on Pippen held aloft as Exhibit A. Some even called for Chuck Daly to be removed as the Olympic coach.

Legendary Pistons public relations director Matt Dobek, in an attempt to stem the bleeding, drafted an open letter from Rodman to Pippen and the Bulls apologizing for his actions. Dobek urged Rodman to sign it so he could release it to both the Chicago and Detroit media.

“I didn’t write that thing, and I didn’t want to sign it,” Rodman admits now. “I felt it was a sign of weakness on my part, and a sign of weakness of the Bad Boys. But eventually I did it.”

The letter was received with both skepticism and derision. Pippen publicly questioned whether Rodman wrote it or even endorsed it. The bad blood between the two players was cemented.

The irony was that Pippen, drafted a year after Rodman in 1987, quickly became The Worm’s favorite player. Both had come from small Midwestern programs and had beaten the odds to make it to the pros. Pippen was a former walk-on at Central Arkansas, Rodman a transfer at Southeastern Oklahoma State.

“I felt like our games were similar,” Rodman says. “We were both wiry, relied on our energy, our defense, to make a difference in the game. And we were both learning on the job. … We weren’t the smartest guys out there because we hadn’t been playing as long as some of the others. But we got there.”

Rodman studied Pippen on film, noted how he used his quickness to herd offensive players away from their sweet spots. He marveled at how Pippen could weave in and out of traffic as if the ball were attached to his hand, the byproduct of handling guard duties when he was a slight, skinny kid playing pick-up games in the dirt.

“At that time, people were calling Larry Bird the quintessential forward,” Rodman says. “He was great, but he couldn’t play multiple positions like Scottie could. He wasn’t agile enough. I just don’t think people realize what Scottie was doing in 1991.

“He revolutionized the point-forward position. All these players today should thank Scottie Pippen. Guys like Kevin Durant should say, ‘Wow, look what you did for us.’ Scottie could handle, he could shoot the ball, he could defend, he could rebound.

“If LeBron was playing during the ’90s, I’d still say Scottie Pippen was the second-best player behind Michael.”

WHEN THE BULLS acquired Rodman on Oct. 3, 1995, Pippen expressed mixed feelings about bringing on the guy who had left him with a scar on his chin. Rodman was equally ambivalent. He was summoned to general manager Jerry Krause’s home for a meeting with Jordan, Pippen and Jackson.

Jackson tapped Rodman on the shoulder and asked to speak with him outside in the garden. The Zen Master said, “Do you want to play for the Chicago Bulls?”

“I told him, ‘Honestly, I don’t really give a damn,'” Rodman says. “I still had some of the history between us in the back of my mind. Phil told me if I wanted to be part of the team, I had to go inside and apologize to Scottie.”

Rodman maintains he rarely spoke to Jordan or Pippen off the court, but it became clear to him that the difference between their first championship run and the final three titles was how much Jordan had come to appreciate Pippen and embrace him as a near-equal.

“We could all tell in those early years Michael didn’t totally trust Scottie,” Rodman says. “In that Game 7 [in 1990], Scottie has a migraine, and he’s seeing double, and his vision is blurry, and his head is pounding, and they’re coming out of the locker room, and Michael is asking him, ‘Are you ready?’ And Scottie can’t go. And Michael is so pissed at him. It will always be a sour note for him.”

From Rodman’s perspective, the desire to compete at the highest level outweighed other concerns for Jordan. But Rodman says Jordan learned over the years that Pippen’s competitive fire was there too. He just didn’t express it as overtly.

“By the time I got there, it was unspoken — ‘You can trust me,'” Rodman says. “They knew it was up to them every night. If MJ was off, Scottie picked up the slack. If Scottie was off, then MJ did it.

“They controlled everything. The rest of us just followed their lead. It was amazing to watch, actually. They were so in sync with each other, especially in that final season.”

Rodman says Pippen’s surgery that year, and his brief trade request, was neither a distraction nor a point of discussion among the players.

“People don’t realize that Phil talked to us every day, in every practice, about focusing on that final year,” Rodman says. “He pounded us with that. We could have folded, we could have packed it in, but nobody did. So one day Scottie comes back — I don’t know who made him come back or why he did, because we didn’t talk about it — but he put on his sneakers and didn’t miss a beat.”

Pippen and Jordan occasionally became frustrated with each other, Rodman says, as all teammates do. But for the most part, he recalls them as united in grabbing that sixth championship. Still, he too wonders where their relationship stands today. “What I’d like to know is, does Scottie really like Michael? Does he care about him? Did he despise him at one point in his career?” Rodman says. “I’ve asked him in so many words, ‘What’s up with you and Michael?’ He doesn’t really answer.”

Recently, Rodman and Pippen have worked together on some dual paid appearances, and they text each other on a fairly regular basis, a vast departure from their playing days.

“It’s hard for Scottie when people say negative things,” Rodman says. “He doesn’t like it. I keep telling him, ‘You have nothing to apologize for. You were one of the best.’

“I hope people can finally see that.”