It was a 6am start on the shores of the Black Sea. Bikes loaded, all 258 riders were ready to set off and follow their carefully plotted GPS routes towards victory and the Atlantic Ocean.

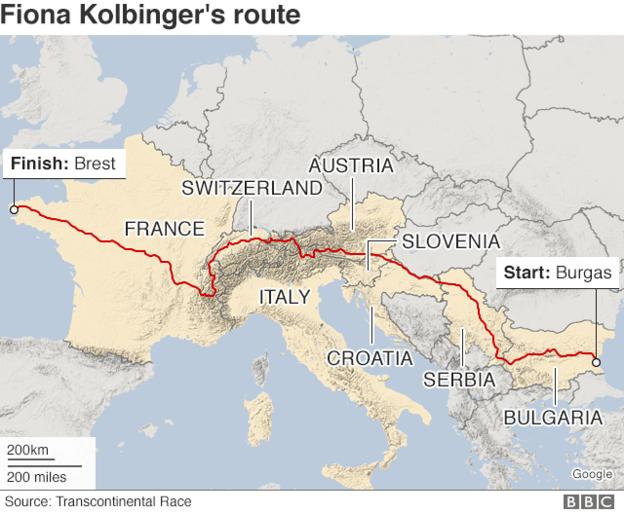

This was the scene at the Transcontinental Race (TCR) start line in late July 2019. An ultra-endurance, self-supported and self-navigated bike race across Europe, the 2019 edition took in 4,000km (2,485 miles) between Burgas on Bulgaria’s coast and Brest in north-west France.

That’s around 600km longer than a typical Tour de France, which takes place over three weeks including two rest days. The winner, 24-year-old German Fiona Kolbinger, completed the TCR in just over 10 days.

Kolbinger is the first woman to win the race. She beat second-placed Briton Ben Davies by over eight hours and third-placed Dutchman Job Hendrickx by 10 hours. Her dominant victory might have surprised many, but ultra-endurance events tend to have less of a gender divide. There is only one race – and it’s about smart decisions and resilience, as well as who can pedal quickest.

Since August a lot has changed for Kolbinger. She has begun work as a newly-qualified doctor, has had time to reflect on the summer, and her body has recovered from cycling 400km a day while sleep deprived.

Looking back now, she sees adventure, success and surprise in a story which, she hopes, will inspire.

The TCR is no ordinary race. Carrying everything you need for up to two weeks’ competition means identifying the absolute essentials: food and water, a pot of chamois cream for saddle sores, one set of cycling kit which can be hand washed, and something to sleep in.

Tent? Forget it. A sleeping bag will suffice – on the side of a road, at the back of a supermarket or in front of someone’s door. Kolbinger describes this existence as “hygienically catastrophic”.

There were four checkpoints along the way to Brest: the Buzludzha Monument in central Bulgaria, Vranje in south Serbia, Pettneu am Arlberg in west Austria, and L’Alpe d’Huez in the French Alps.

Kolbinger impressed from the start.

She arrived at the first checkpoint inside the top five, but it was only during the second night, when the race got to Serbia, that she took the lead “by accident”. Her entry into the country was spectacular. It was a day involving three punctures and two crashes – one at the Bulgarian-Serbian border.

“There was another rider standing right next to the border barrier, so I was waving looking to the side. I didn’t see the barrier so I crashed right into it,” Kolbinger remembers.

“I fell, the border barrier was bent and the border police confiscated my passport for about half an hour. I was like, ‘hey I’m on a race, how long is this going to take?’, and they said: ‘We don’t know because we’ve never had someone crashing into this.’

“When I finally left, I rode north further into Serbia and needed to get some food. I went into a gas station and it was pouring down so then I thought, ‘OK it’s 11pm, I could sleep now instead of getting soaked with limited vision’. So I laid down, but it was a really shady place.

“It was a huge parking lot with a gas station and a strange hotel and lots of buses and tourists around. I slept in a little hut. I couldn’t really sleep so I woke up after two hours and decided to just continue because the rain had stopped. And so that was how I ended up starting the day at 1am and overtaking everyone else.”

Kolbinger then found she needed to stop in the morning – “for a nap” – and lost the lead. But she wouldn’t trail for long.

Crossing from Slovenia into Austria was one of her toughest days. She covered 475km and slept at an unmanned campsite just over the border for a few hours. Shortly after setting off in the very early morning, she saw a red glow up ahead. It looked like a rear bike light. It was Ben Davies.

“There were three of us who had been pretty close since Serbia,” Kolbinger says. “Jonathan Rankin, Ben and me. I was expecting to be racing them decently for at least 200-300km, everyone checking the online tracker and not losing each other. But it wasn’t like that.

“Ben and I cycled next to each other for about 15 minutes, then I took a left turn and he went straight. I didn’t see him again.”

Davies’ route took him south, while Kolbinger went north. Then she found Rankin.

“I saw more red lights in front of me again and I thought, ‘wow that must be Jonathan’. I tried to keep the pace and not lose sight of the light and then suddenly it was gone. I thought he must have turned or stopped somewhere.”

Kolbinger recalls checking the GPS tracker which shows each rider’s progress soon afterwards to discover that, once again, she was the race leader. She heard later that Rankin retired soon after she spotted him because of problems with his feet. “Feet have started to disintegrate, for lack of a better description,” were his words to race director Anna Haslock.

Kolbinger continued, pushing herself as hard as she could, still mostly sleeping rough. She did stay in a hotel for two of the 10 nights, which helped to keep devices charged, but mostly she unrolled her sleeping bag anywhere. By the side of the road, on grass or at the back of a supermarket, where she was woken up by an early morning delivery. “That was really stupid,” she says.

She was seven days into the race when she crossed into France and reached the final checkpoint before the finishing line at L’Alpe d’Huez. Still in the lead, with the toughest climbs behind her, it was a moment of release.

When she walked into the hotel foyer to get the stamp in her race passbook, she found a piano and immediately sat down to play The Lion Sleeps Tonight, helmet and gloves still on. The video clip caught attention on social media, because surely the race leader would have more important things to be doing? Davies was still chasing behind – there was still well over 1,000km to go.

Not Kolbinger. She sat down and started playing – still feeling mentally “fresh” despite the physical toll and lack of sleep.

She would spend two more summer nights under the stars before reaching Brest. On one of those she was mistaken for a rough sleeper.

“I was trying to go to sleep and it was about 1am on a Saturday night,” she says. “I’d decided to sleep in front of this housing building. I fell asleep, and then after about half an hour this lady came, coming home from partying probably, and she found me in front of her door. She was really shocked that a young woman was there in a sleeping bag on the cobbles in front of her house, it must have been so strange to her.

“She offered me food and drink but we are not allowed to take anything because of the rules. She didn’t speak any English so it was really hard to tell her in my limited French what we were doing. I showed her the TCR homepage and tried to explain that I was the leading dot, and that I just wanted to sleep and she could go into her home and let me! I don’t think she really understood the goal of this entire thing.”

By that point Kolbinger was on the home straight – far enough ahead of Davies for the risk of being caught to be small. She had also switched off her phone because, already back in Austria, she was so far ahead she was inundated with messages, social media comments and requests from journalists. They all wanted to speak with the first woman to win the race.

The actual finish was something of an anti-climax – which is often the case at ultra-endurance events. As the city residents of Brest awoke on a grey Monday morning, Kolbinger rolled into a hostel car park, dismounted one final time and stopped the clock to officially become the race winner in just over 10 days.

Davies would arrive eight hours later, and the rest of the field would slowly appear over the next five days. Kolbinger turned her phone back on and processed what she had achieved.

She describes herself as somebody who is naturally outspoken and will call out something she feels is unjust. Gender equality is a subject close to her heart and was already something she thought about in everyday situations. Now she feels its importance from a new perspective.

“I have the impression that, especially in male-dominated groups, sometimes women are just underestimated because of their gender,” she says.

“Now that I have done this exceptionally ‘male’ thing [in] winning this race, I feel like they do accept me a bit more – or I feel like I get a bit more respect without anyone mentioning it. There is less underestimating me right now.

“If you understand what I mean, it’s different in that I’ve shown I’m not the ‘weak female’ so I think this gives me a bit more respect. Which is sad on the other hand, because I feel like before they didn’t respect me so much. It’s really sad to think about it that way – that the ‘ordinary’ woman who hasn’t done any crazy race or crazy ‘male’ stuff in her life, like climbing Mount Everest or something, she wouldn’t get that respect.

“I think some media has interpreted this as if I had changed the world entirely and shown that women are capable of doing things… surprisingly… and I didn’t really expect to become such a women’s ambassador in the media.

“They are comparing me with Jasmin Paris who won the Spine Race and Lael Wilcox doing really well in the Silk Road Mountain Race, and all of these successful women in sports, especially ultra-endurance sports. And that kind of surprised me that I was in that role, but I do think I like that role and I can take it.

“I think I have a talent – apparently – that I didn’t really know about until the summer, and if I can use this talent to promote equality then that’s perfect.”

The TCR was founded by Mike Hall, a British ultra-endurance cyclist who was killed after being hit by a car during a race in Australia in 2017. His partner Anna Haslock now runs the race. She describes herself as its “caretaker”.

Since the first edition in 2013, the number of female competitors has grown from one in a field of 31 – Juliana Buhring, a British-German cyclist who set a world record in 2012 as the fastest woman to circumnavigate the globe by bike – to 31 women in a field of over 265 in 2019.

“It didn’t feel like an impossible thing that a woman would win,” Haslock says. “In endurance sport I think the addition of route planning and so many additional elements to the race definitely levels the playing field.

“People will say when they finish it’s probably 70-80% mental strength. You have to be fit but you have to be able to handle the unexpected and you have to know yourself really well, because you’re spending two weeks on your own, just you.

“For a lot of people it’s a bit of a mind-melting exercise. The people like Fiona, the people who win these races do not panic. They cope with things and just deal with it.

“But it’s thrilling to see a woman win it and especially when it’s in such style and grace. I’m not saying it’s an easy thing what Fiona did, but she could’ve been pushed harder and she says that herself.

“She could do it in under 10 days for sure. Almost as soon as she got off the bike she said: ‘How do I sign up for next year?'”