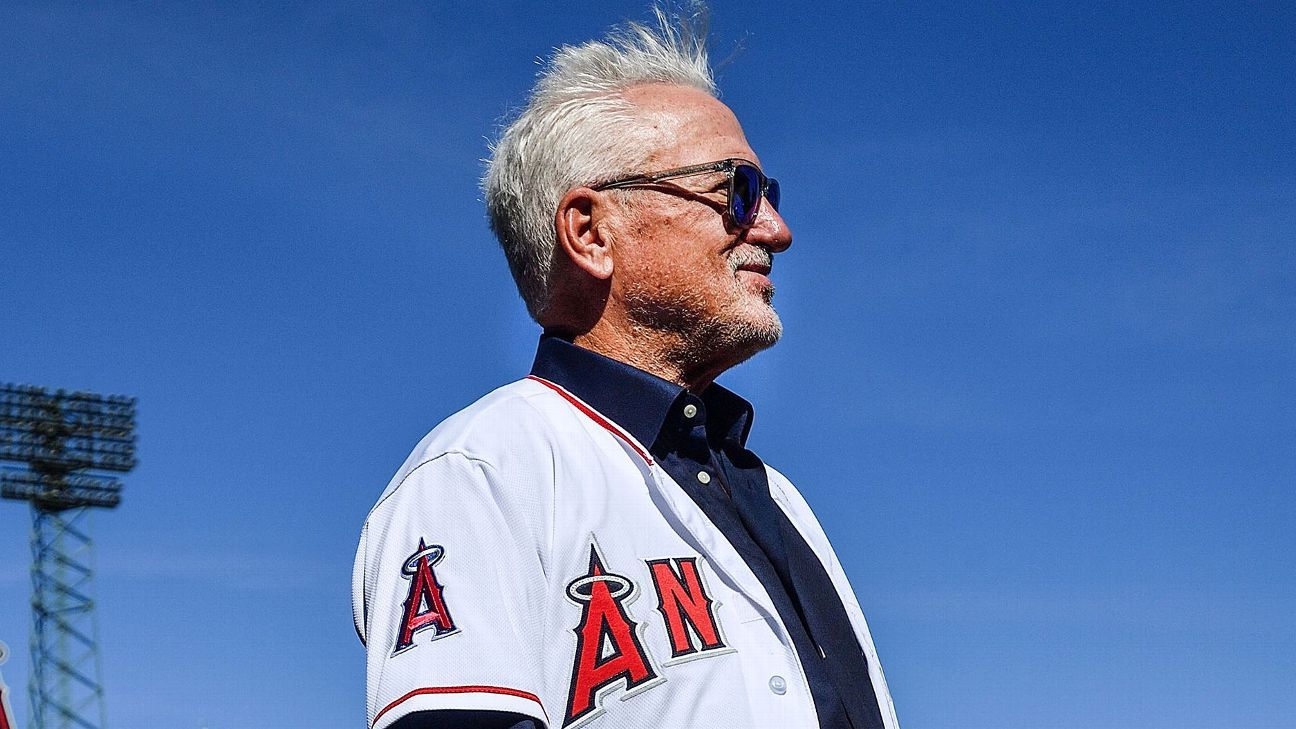

LONG BEACH, Calif. — Joe Maddon settled into a small Italian deli bordering the Pacific coast Friday, only a block from the high-rise condominium that housed him for the past month, and instantly felt regret. He wished he had spotted this place sooner. The next day, on the morning of his 66th birthday, he would depart for Arizona to begin his new job as field manager for the Los Angeles Angels and hit the ground running on another long, arduous baseball season. He had discovered something appealing at a time when he could no longer truly enjoy it.

“Such is life,” Maddon said between sips from the black Yeti Rambler that held his coffee.

This offseason offered few other disappointments. Maddon usually spends the bulk of his offseason in Pennsylvania or Florida, but he made it a point to descend upon Southern California early and attack the remaining weeks with purpose. He arrived by Jan. 15, his target date, and spent the next 22 days getting reacquainted with the place that precipitated his greatest professional growth.

He forged a stronger relationship with the Angels’ general manager, Billy Eppler, who is entering the final season of his contract and would have had every reason to feel uneasy about Maddon’s celebrated return. He connected with a long list of old friends from an organization that previously employed him for 30 years. He introduced his foundation, Respect 90, to a region with a homelessness crisis. He rode his bicycle along Ocean Boulevard, got his diet back in order and finally shook the sinus infection that hampered most of his winter.

Most of all, Maddon paused and reflected.

He often found himself feeling nostalgic, sentimental, rejuvenated.

“The good thing,” Maddon said, “is I’m seeing it with first-time eyes, I’m feeling it with first-time passion, which doesn’t occur normally when you get to this point in your career or your life.”

Maddon went from light-hitting catcher to minor league manager to roving hitting instructor to major league coach while with the Angels from 1976 to 2005. He served as Mike Scioscia’s bench coach for the last six seasons of that stretch, capturing what remains the franchise’s only championship along the way, then spent the next 14 years becoming one of the game’s most successful managers, lifting the small-market Tampa Bay Rays to new heights and guiding the Chicago Cubs to their first World Series title in more than a century.

On the morning of Sept. 29, Maddon stood alongside Cubs president of baseball operations Theo Epstein at Busch Stadium as the two tried to explain why they were parting ways after the most successful half-decade in franchise history. A little more than four months later, Maddon reasoned that it was “time for both sides” to move on. He said he had come to the realization that he didn’t want to return to Chicago while the 2019 season was still ongoing, regardless of the outcome.

“It was plenty,” Maddon said. “Philosophically, Theo needed to do what he needed to do separately. At some point, I began to interfere with his train of thought a little bit. And it’s not that I’m hardheaded. I’m inclusive. But when I started there — ’15, ’16, ’17 — it was pretty much my methods. And then all of a sudden, after ’18 going into ’19, they wanted to change everything.”

The Cubs fired three coaches after the 2018 season, but Maddon said the front office also “wanted to control more of what was occurring in just about everything.”

“There was just, you can say, philosophical differences,” Maddon continued, referencing his relationship with Epstein. “But he and I are still good friends. And I like the man a lot. It was just time for him to get someone else and time for me to work somewhere else. That’s all. A five-year shelf life in Chicago is almost equivalent to five to 10 somewhere else. At the end of the day, man, there’s nothing to lament there. That was the most successful five years that the Cubs have ever had.”

Maddon quickly garnered interest on the open market, just as Epstein predicted. The New York Mets, the Philadelphia Phillies and the San Diego Padres all checked in. But first, Maddon needed to see whether a return to the Angels made sense. He dined at Mastro’s in Newport Beach with team owner Arte Moreno, president John Carpino and Eppler days after the Angels had fired manager Brad Ausmus, then signed a three-year, $12 million contract shortly thereafter. He never met with another team.

“I just thought it would’ve been disingenuous to accept interviews with anyone else if I truly wanted to be here,” Maddon said. “And then, after it was all set and done, it couldn’t have been more obvious it was the right thing to do for me.”

Maddon felt a comfort with Moreno and Carpino, two men he built a relationship with in the early 2000s. But he also quickly came to admire Eppler for his drive and his transparency. He liked that he had an analytical mind but came up under the tutelage of respected scouts such as Gene Michael and Bill Livesey. Maddon sat alongside Eppler in Orange County to recruit Gerrit Cole and in Atlanta to recruit Zack Wheeler. Both pursuits failed. Instead, the Angels signed Anthony Rendon, the best position player on the free-agent market, and tried to address a needy rotation on the margins, adding Julio Teheran and Dylan Bundy.

The Angels are coming off a 90-loss season and a fifth consecutive year without making the playoffs. They have employed the game’s best player, Mike Trout, for the past eight years and don’t have a single postseason victory to show for it. But the franchise is reeling in a larger sense. Tyler Skaggs, a promising and effervescent young pitcher, died of a drug overdose on July 1, triggering revelations that opioids might have been prevalent in the Angels’ clubhouse. A federal investigation is ongoing; the Skaggs family has threatened litigation; and a dark cloud continues to hover over the franchise.

Maddon wasn’t there for any of this, but he is no stranger to tragedy with the Angels. He was with the organization when Mike Miley died in a car crash in 1977, when Lyman Bostock was shot the next year, and when Donnie Moore killed his wife and then himself in 1989. When Nick Adenhart was killed by a drunk driver early in the 2009 season, Maddon still felt a deep connection with the franchise.

“We’ve had some awful things occur here, but so does everybody else, you know?” Maddon said. “Look what just happened to Kobe Bryant, what this whole area is overcoming right now. It’s about continuing to move forward, it’s about trying to learn from your mistakes, it’s about trying to not repeat your mistakes or bad decisions, and just try to continue to develop the group. I work from a position of positivity always. I don’t dwell on negativity, and I always believe something better’s on the horizon.”

Maddon has spent the offseason working on how to slow things down in his head. He’s big on meditation and sensing the moment and taking notes and identifying the initial source of his ideas. When asked what was left to accomplish in a career that might already have earned him a spot in the Hall of Fame, the three-time Manager of the Year smiled and said, “I’m a journey guy. I’m motivated by the day.”

Maddon was lauded for his data-driven approach to baseball during his early days on the Angels’ coaching staff, then led a Rays franchise that expertly used analytics and market inefficiencies to counteract its financial restraints. But Maddon believes fervently that the game has swayed too far in that direction. He thinks analytics and technology “are responsible for subtracting the passion from what we do, not only in sports but in our regular lives.” He wants to dial it back.

“I think somebody’s got to stand up for our game and the way it is and it should be played, and what should be tinkered with and what should not,” Maddon said. “My conclusion is analytics and technology are slightly responsible for putting the game in a position where it’s not as attractive to fans.”

Maddon wants the Angels’ alumni to become deeply involved with the organization. He wants his team to be aggressive on the bases, wants to maximize the skills of an offense that was among the sport’s best at putting the ball in play last season, wants to — gasp! — call for the occasional sacrifice bunt. Maddon prides himself on progressive thinking, but he can’t help but feel wary about modern behavioral patterns. Often he’ll think core values are being shoved aside and work ethic is elusive and technology is sapping our collective joy. But then he’ll ask himself a fundamental question: Am I just being 66?

“I don’t want to be a 66-year-old man banging on youth,” Maddon said, “because that’s not my agenda.”

Maddon bought a house in Belmont Shore, an upscale neighborhood in Long Beach, about a dozen years ago. He stopped using it three years later but never sold it. His wife, Jaye Sousoures, loved it too much. A friend’s family is currently living in the house, but Maddon will settle back in shortly after he returns from spring training in late March.

ESPN Daily Newsletter: Sign up now!

The journey back here began right before the end of 2019, when Joe and Jaye loaded up the RV and left his hometown of Hazelton, Pennsylvania. They celebrated New Year’s Eve at a bed and breakfast in Roanoke, Virginia, then spent the next five days driving to Arizona, where the RV would sit idly until pitchers and catchers reported. From there, Maddon flew to Florida to host a charity event at his Tampa home, then flew to Southern California to begin preparing for the job that awaits.

He had beers with old scouts and shared dinner with old coaches, usually in places that still felt so familiar. He drove past old neighborhoods and made several stops at the old ballpark and felt wistful through most of it.

“This is like, weirdly, as comfortable as going home,” Maddon said. “And I can’t say that about any other place.”

There’s one stretch along the Pacific Coast Highway that never fails to give Maddon butterflies. It happens every time he heads south toward Huntington Beach, hangs a slight right and gets over a hump while crossing Warner Avenue. Suddenly the pier is visible in the distance, as is what seems like an endless stretch of sand, ocean and palm trees.

“That, to me, equals Southern California,” Maddon said. “I’m never not impressed by that. Another phrase that I’ve been telling myself is, ‘Don’t miss it.’ We speed through everything. You miss the sights, you miss that look. I missed sitting here the last three weeks because I was stupid about it. See it with first-time eyes, do it with first-time passion, and don’t miss it.”