Patrons at a small bar in Pocatello, Idaho, were a bit confused as to why a stranger showed up intent on watching the Harvard-Yale football game one day in 1982. He tried to explain, but no one really paid much attention until he offered to buy all the beer.

Had they been listening, they might not have believed him. He was only there because he received a cryptic phone call that consisted of just three words: “Watch the game.”

Still, the message was received. There was only one reason he could have received such a strange call: After four years, plans for an elaborate prank he helped design as part of a group of MIT students — to this day willing to identify themselves publicly only as the Sudbury Four — had been put into motion.

The mission: to bury a weather balloon beneath the grass at Harvard Stadium and then inflate it during the middle of the game.

By the time the game was over, he was the one drinking for free.

This Saturday, Harvard and Yale will meet for the 135th time, with the game to be played at Fenway Park in Boston (noon ET, ESPN2). Yale leads the series with a 67-59-8 head-to-head record.

At least that’s the way the series looks in the official record books.

There’s a third school — one that went decades without a football team — that managed to insert itself into The Game’s lore several times and might want to claim one win for itself. While athletic success is a huge source of pride for many universities, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is different. For years, its culture of hacks — or large-scale pranks intended to be harmless fun — has filled that role. And because of MIT’s proximity to Harvard and the academic rivalry between those schools, the Harvard-Yale game has served as a natural target, dating back at least 70 years.

It was at the 1982 game, however, that a group of MIT students pulled off arguably the greatest hack in MIT history — the culmination of five years of planning, dozens of surreptitious overnight visits inside Harvard Stadium and several other failed ideas.

The balloon prank required so much planning and technical know-how that it has to go down as the greatest in college sports history, one that could never be duplicated.

At some point in the mid-1970s, a former member of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity at MIT was back at the house for an alumni dinner. Sharing stories about the good ol’ days, it was only natural for him to tell a firsthand account of perhaps the most legendary story in the fraternity’s history: the time in 1948 when he and seven others — a few years after they returned from World War II — almost pulled off an epic prank at the Harvard-Yale game.

Drawing on demolition skills used during the war, they successfully installed primer cord — used to detonate large explosives — below the grass at Harvard Stadium and had blasting caps ready to spell out M-I-T in 15-foot letters. They ran wire off the field and would need batteries to set off the charges during the game a few days later. However, two days before the game, groundskeepers noticed excess wire left behind during the installation and notified police.

The primer cord was removed from the field, but police left the excess wire untouched. Then, in shifts for the next 48 hours, they waited. On the day of the game, the man tasked with setting off the charges was apprehended by a plainclothes officer underneath the bleachers just minutes before the game was set to kick off. He was quizzed about why the trench coat he was wearing was full of batteries.

So the story goes, he told the officer that “all MIT men carry batteries for emergencies.”

In big, bold letters on the front page of the Boston Sunday Globe the next morning, it read: “AVERT BLAST AMONG 57,621 at H-Y GAME.” Underneath: “Explosion Plotted by 8 Student Pranksters — Enough Nitrate to Blow a Crater, Police Say.”

Police let Harvard officials decide whether they wanted to press charges and — in a sign of the times — they passed. However, several members of the fraternity were expelled from school for the term.

For decades, the tale was passed down from class to class. There were various ideas and attempts over the years to “finish the mission,” but none of them proved successful.

Eventually, that’s how the Sudbury Four were inspired to come up with a new plan

Part I: Resurrecting the mission and designing the device

The Sudbury Four got their name because they rented a house together in the Boston suburb of that name about 20 miles from the MIT campus. For no particular reason, one of them came home one day with a box full of weather balloons purchased at a surplus store.

Their dining room table consisted of a 4-by-8 piece of plywood that was supported by cases of beer. It was at that table they came up with the idea to deploy one of the weather balloons during the Harvard-Yale game in 1978. They fleshed out the concept more and decided to design a device that would be able to inflate a balloon from beneath the grass during the middle of the game.

“As we worked on this thing, the table would get lower as we drank the beer,” a member of the Sudbury Four said. “And every now and then, we’d have to go make a beer run and replenish the height of the table.”

All four had graduated at this point and were either pursuing graduate or additional undergrad degrees from MIT. Once they came up with blueprints for the cylindrical device, they cobbled together parts from wherever they could: a motor from one of their mother’s electric can openers, contact points from a 1967 Ford Mustang and, most famously, a piece from a leather motorcycle jacket to create a piston seal.

One of the members in graduate school was working on a nuclear fusion project and had access to the Francis Bitter Magnet Laboratory, which then served as the national magnet lab. He was able to use the facility to work on the device as they went through an exhaustive process of trial and error.

During this time, they made about a dozen late-night scouting trips to Harvard Stadium — dressed in all black, naturally — to figure out how to bury the device and run the necessary wiring to an electrical power source. One night, they ran into another group of pranksters from Brown University, there to douse the field with salt in the form of a “Y” — thinking the dead grass would somehow get Yale students in trouble.

Eventually, the Sudbury Four was able to successfully install the wiring they needed. The last step would be to dig a hole 3 feet deep, drop the device in it and attach the device to the wiring. Once they laid the grass back over it, they would be almost good to go. But when they returned to the stadium to execute this part of the operation, there was a tarp on the field to protect the grass from the rain, a Harvard Police car was parked near the field and security guards were on duty. The plan was foiled.

The day after the Harvard-Yale game, they buried the device in their backyard in Sudbury and scheduled a party for May 19, 1979. It would be a test to see whether the device would work after spending several months underground. They theorized that it might be easier to install it during the summer, when there was less security, and activate it at a later date.

They still remember the party fondly — lots of people showed — but the device didn’t work.

“I think we packed it up and sealed it up in 1979 after we had done that six-month underground test and so forth,” one of them said. “And then I think that was kind of it. I think we all decided we really needed to work on finishing graduate school, getting a job and things like that. We kind of stopped working on it.”

Added another: “It damn near flunked all of us out of school trying to get this device built and solve all the problems.”

Part II: “It’s now or never”

Four years later, in 1982, the Sudbury Four had gone their separate ways, but the idea to deploy the device was still alive inside the Deke house.

“I think there was a group of us were sitting around, and we talked about it from time to time, ‘Why don’t we go do it?'” Dave Bohman said. “And finally it was my junior year there in the fall of ’82 that we just said, ‘Let’s do it. We just got to do it. It’s now or never.'”

A group of about seven core members decided to take it on. They obtained the device from a member of the Sudbury Four who still lived locally and received a tutorial on how to operate it. He filled them in on what could go wrong and was generally available in an advisory role.

They farmed out the different responsibilities according to each individual’s technical expertise, and over the course of about three weeks took eight separate trips to Harvard Stadium — dressed in Army fatigues this time — to run the wires and install the device. Each night, they would have members stationed at the top of the stadium looking for police and would signal down with a flashlight if there was a need to go into hiding.

There was only one minor scare. As a civil engineering major, Chris Kennedy was tasked with digging on the field, and he was out there one night when a police car rolled up to the open end of the horseshoe-shaped stadium.

“If you stood up, you would cast a shadow a couple hundred feet,” Kennedy said. “So I’m just laying down on the field, my heart pumping. And the cop car stayed there for what seemed like 30 minutes.”

When they returned home later that night, they were nervous it was getting too close to game day and briefly considered pulling the plug on the operation. But it didn’t take much encouragement from other members of the fraternity to keep going.

It was a significant challenge to get power to the device and keep the wires out of sight — the fatal flaw in the 1948 attempt — but they managed to pull it off by running wire to a mechanical room underneath the bleachers that powered the field’s irrigation system. The way the device was designed, it would have been nearly impossible for anyone but them to activate it because it required a double male extension cord.

Part III: Finishing the mission

On Nov. 20, 1982, California lateraled the ball five times on a kickoff return and avoided Stanford’s band to score a touchdown in arguably the most famous play in college football history. But before a trombone player was toppled that day during The Play, first came Delta Kappa Epsilon’s execution of The Prank.

Wary of what happened in 1948, when the police got involved and expulsions were handed out, the members kept a tight lid on their plan.

Bohman wrapped the extension cord around his waist and brought it into the stadium under a black wool overcoat. The pranksters didn’t want the balloon to disrupt a play, so they positioned themselves in a way to be able to relay to Bohman when it was safe to activate the device. When the time was right, he plugged it in, and they all ran to various places inside the stadium to get a glimpse. Nothing happened.

“So we all went down under the stadium and we talked about it,” Bohman said. “It could’ve been anything. We’re all engineers, and so we thought about what the problem could have been.”

They agreed there were two possibilities: There was an issue they wouldn’t be able to solve with several thousand people around — a cut wire, perhaps — or the power source wasn’t turned on. Another member, Bill Doyle, went back into the room and found a breaker switch that needed to be flipped. He switched it on, and away they all went, running back into spots to watch the balloon inflate.

This time, it did.

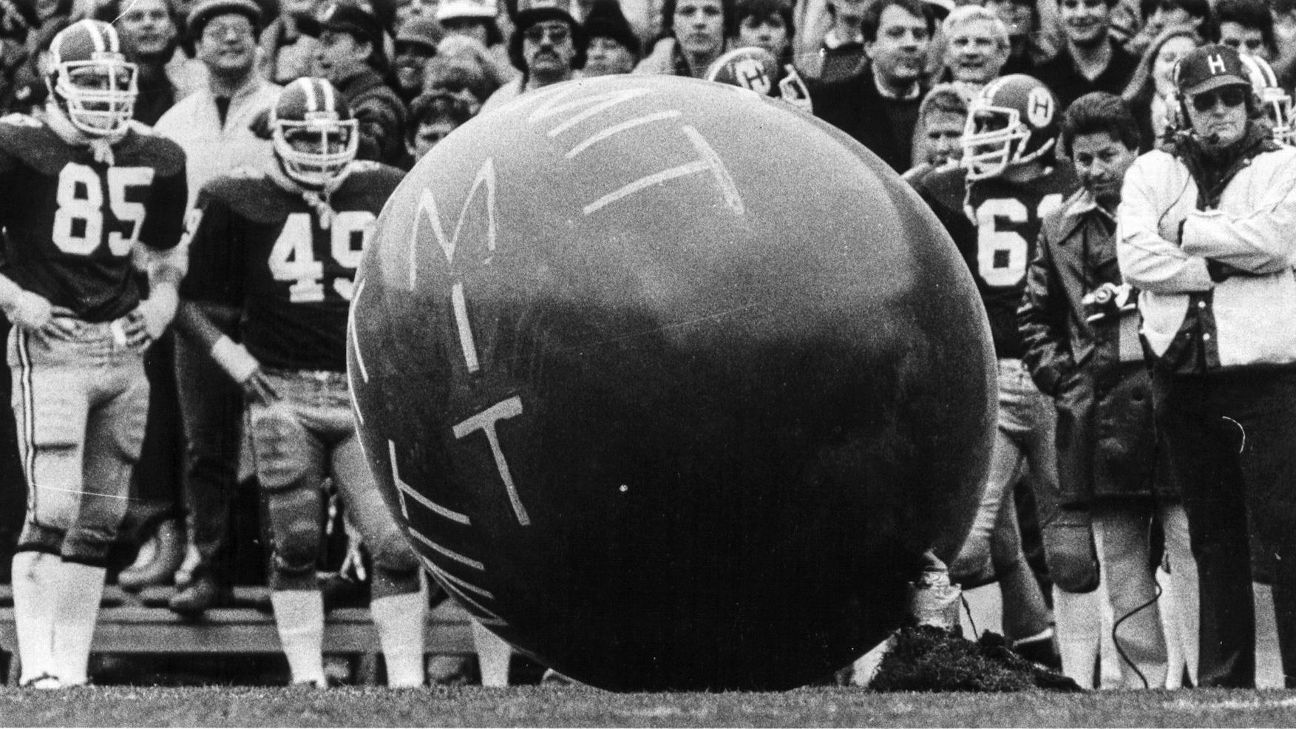

With 7:45 left in the second quarter, just after Harvard scored a touchdown, the black weather balloon with MIT written all over it in white lipstick emerged from the earth near midfield by the Crimson sideline. It grew and grew until it reached about 8 feet in diameter. At least one Harvard police officer pulled his gun. Finally, it popped, releasing a puff of white powder that looked like smoke.

Dave Webster, a recent graduate, had left a note inside the device with instructions on how to put it back in the ground. The game resumed a few minutes later, and Harvard went on to win 45-7, but the real winner was MIT — a school without a football team.

Just as in 1948, the MIT hack made the front page of the Boston Sunday Globe.

“I sat there and didn’t really know what to think,” said Harvard president Derek Bok, according to the Globe. “I thought the Phoenix was again rising from the ashes.

“My first reaction was that they have an awful lot of clever people down there at MIT and they did it again. I still don’t understand how they did that, making a balloon rise as they did.”

In a story in the MIT student newspaper, under the headline “Saturday’s score: MIT 1, Harvard-Yale 0,” MIT president Paul Gray said: “There is absolutely no truth to the rumor that I had anything to do with the planning or promoting of [the hack], but I wish there were.”

Part IV: Going public

There was a big party at the Deke house the night of the hack, but the members were hesitant to take credit, fearing expulsion or worse. The lessons from 1948 were never far from their minds.

“When this happened, we were getting calls from some of those guys [from the 1948 attempt], who figured it must’ve been the Dekes that did it, which was pretty cool,” Kennedy said. “But we still waited. And, of course, it was in the papers, and it was received so favorably that we started to feel like, ‘OK, maybe we can come clean on this.'”

But not before a call came from the dean at MIT. The fraternity was already on probation, so getting caught could have been problematic.

“I believe it was Bruce Sohn, who was the president [of the fraternity] at the time, who had the fateful call from the dean, who said, ‘Did you guys do this?'” said Webster, who is in the process of attempting to turn the story into a feature-length movie. “And he had to think for a second. ‘If I say yes, this could be the thing that has the straw on the camel’s back and kicks us off campus forever. And if I say no, there might even be more trouble if they found out we did.’ So he goes, ‘Yes sir, we did.’

“And then there’s a pause on the phone, and then the dean goes, ‘OK, you’re off probation.'”

Without any punishment to fear, they decided to call a news conference that can be found on YouTube. No one was sure whether there would be much interest, so to entice local media to show up, they promised an open bar. Sure enough, all the local television stations showed up, and after an impromptu happy hour of sorts, the Dekes took credit publicly.

At the next alumni dinner, members from 1948 got together for the first time in 34 years, showed up at the house unannounced and presented the actives with a plaque.

It read: Thank you for completing the mission

Part V: A lasting legacy

MIT’s long history of elaborate pranks is enough to justify a Hall of Hacks at the MIT Museum, where the device is stored.

Coincidently, the museum’s present-day curator, Deborah Douglas, then an undergraduate student at Wellesley College, was in the stands at Harvard that day in 1982. It’s one of two hacks, she says, that stand out from the rest in terms of how they’ve transcended the normal boundaries of something of interest only to the campus community, with the other being the Smooting of the Harvard Bridge.

“There have been some big changes between then and now,” Douglas said. “Not just that 9/11 has happened, but if something like this happened today, they would probably evacuate the stadium.

“I would say anyone who was there absolutely remembers the event in the stadium. It didn’t evoke the kind of panic that we are sometimes accustomed to seeing in news accounts or whatever, and so it makes me, in many ways, it makes me yearn for those days again.”

Several members who took part in the hack in 1982 agreed: If anyone were to attempt the harmless type of stunt they pulled off — let alone the one in 1948 — it would likely be met with a prison sentence.

In the years since, the story of the hack will occasionally bubble up, usually on some kind of list about the best college sports pranks or MIT hacks.

“Of course, either we’re voted No. 1 and we share that,” Kennedy said. “Or if we’re not No. 1, we’ll complain, like, ‘They don’t know what they’re talking about.'”

Just two weeks ago, one member of the Sudbury Four was having a conversation with someone at a wedding who brought up the hack out of the blue — not knowing the person they were talking to had played any sort of role.

“This person talked about it for a few minutes, and I said, ‘You know I helped build that, right?'” he said. “There was some surprise, some shock and then a little bit of, ‘Yeah, figures.'”

At Saturday’s Harvard-Yale game, there won’t be any concerns about the Deke boys trying to pull anything off. Nearly all the active members are on the MIT football team, which was reinstated as a Division III sport in 1988. The Beavers went 9-1 during the regular season and play at Johns Hopkins in the first round of the NCAA playoffs Saturday.

“We don’t have a prank that we’re planning on this year [at Fenway Park],” a Sudbury Four member joked.

“At least not one that we’re willing to announce in advance.”